The European Union’s (EU) foreign policy chief, Federica Mogherini, recently announced that the EU will set-up a special purpose vehicle (SPV) “to facilitate legitimate financial transactions with Iran and allow European companies to continue to trade with Iran.” In response, our visiting senior fellow, Samantha Sultoon, argued that this SPV will not provide a reliable path around US sanctions, and may undermine the effectiveness of US and EU sanctions in the long-run. This edition of the EconoGraphic explains how the SPV would work in practice and outlines why this mechanism is unlikely to offer Iran enough economic upside to keep the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) alive.

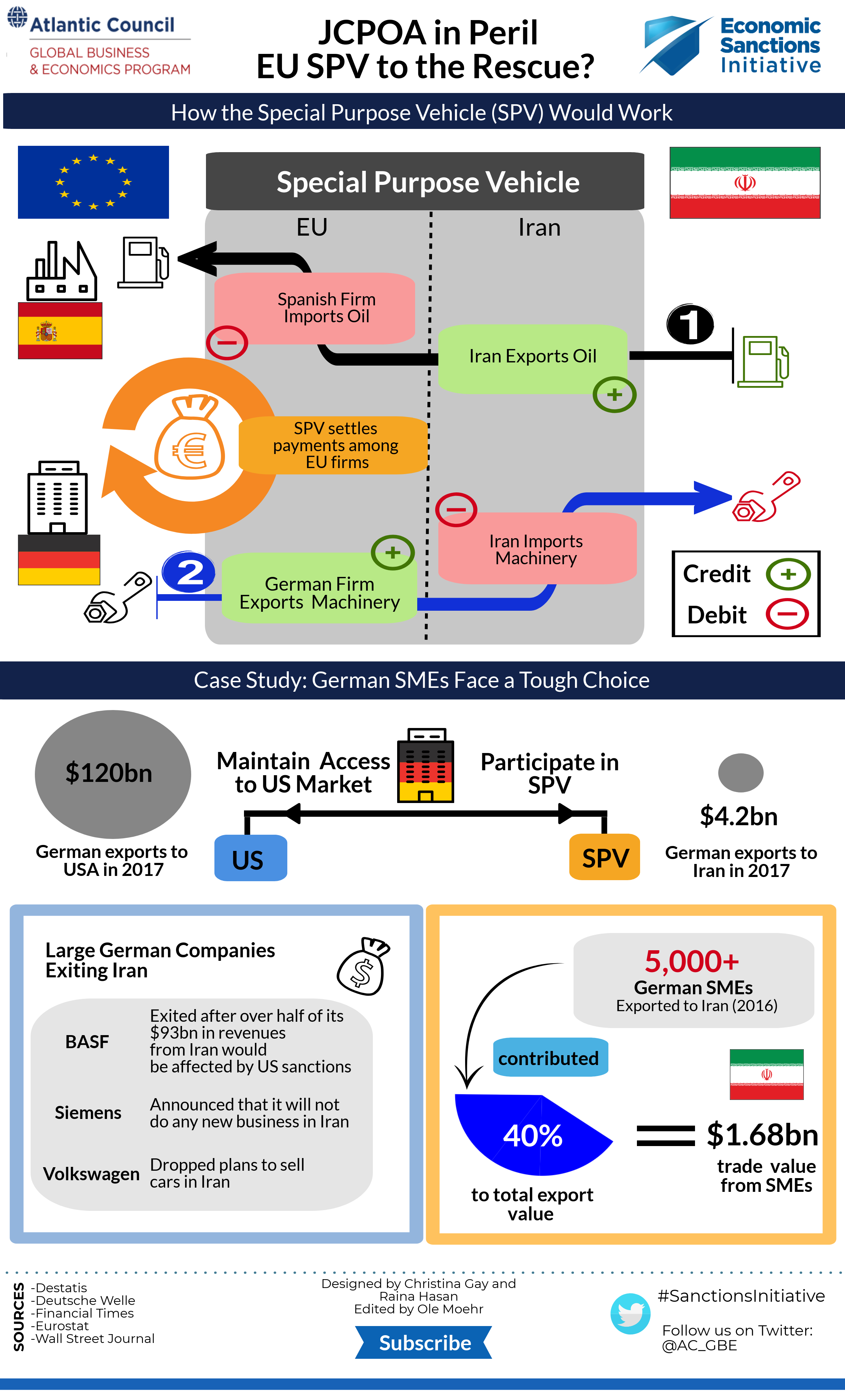

To bypass US sanctions against Iran, the SPV would establish a barter exchange that is neither connected to the US dollar-dominated international financial system nor requires monetary transfers between EU countries and Iran. As Samantha Sultoon detailed in her piece, the SPV would “essentially act as an accounting firm, tracking credits against imports and exports.” In turn, Iran could continue to deliver crude oil to EU firms and purchase goods in exchange. Using euros, the SPV would settle payments among EU importers and exporters without involving commercial or central banks.

The example of Germany, which is Iran’s largest trading partner within the EU, underscores the SPV’s limitations. According to our assessment, the SPV will not be able to effectively protect German firms operating in the United States from US secondary sanctions. The US government will likely deem transactions facilitated by the SPV as problematic. Thus, while the SPV is not relying on the international financial system and monetary transfers, any European company utilizing the mechanism may still be subject to US sanctions. Faced with a choice between the $20 trillion US economy and the $430 billion Iranian economy, we predict that almost all large German companies (i.e., companies with ≥ 250 employees) will choose to continue to do business with the former. That leaves German small–and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) that do not have substantial links to the US economy. SMEs account for approximately 40 percent of the total value of German exports to Iran. This number is much higher than the average 24 percent SMEs contribute to Germany’s overall extra-EU exports. In 2017, 40 percent of German exports to Iran equaled roughly $1.68 billion. If we make the generous assumption that all German SMEs, which are currently exporting goods to Iran, will use the SPV, Iran could deliver crude oil worth $1.68 billion in return. In short, setting-up the SPV will not change large European companies’ risk calculus vis-à-vis Iran, but it might throw a limited lifeline to the JCPOA by facilitating trade between SMEs and Iran.

Our baseline scenario remains, however, that the EU SPV will not provide Iran with enough economic incentives to remain party to the JCPOA in the long-run. Multinational companies, such as Airbus, Daimler, and Total, have already ceased their operations in Iran. Almost all their multinational peers will follow their example ahead of the November 4th deadline when the second, more substantial tranche of US sanctions against Iran will be re-imposed. European SMEs contribute a substantial portion to overall EU-Iran trade. However, we expect a significant share of EU-based SMEs to also pull out of Iran. Finally, the barter system, which we understand is at the heart of the SPV, will not provide a viable alternative to facilitate EU-Iran trade compared with the international financial system that usually fulfills this function. A caveat is the potential participation in the SPV by countries, such as China and Russia, whose governments can direct companies to continue to trade with Iran. Particularly China, which is the largest importer of Iranian oil, may be able to absorb some of the decline in oil exports that Iran is facing.