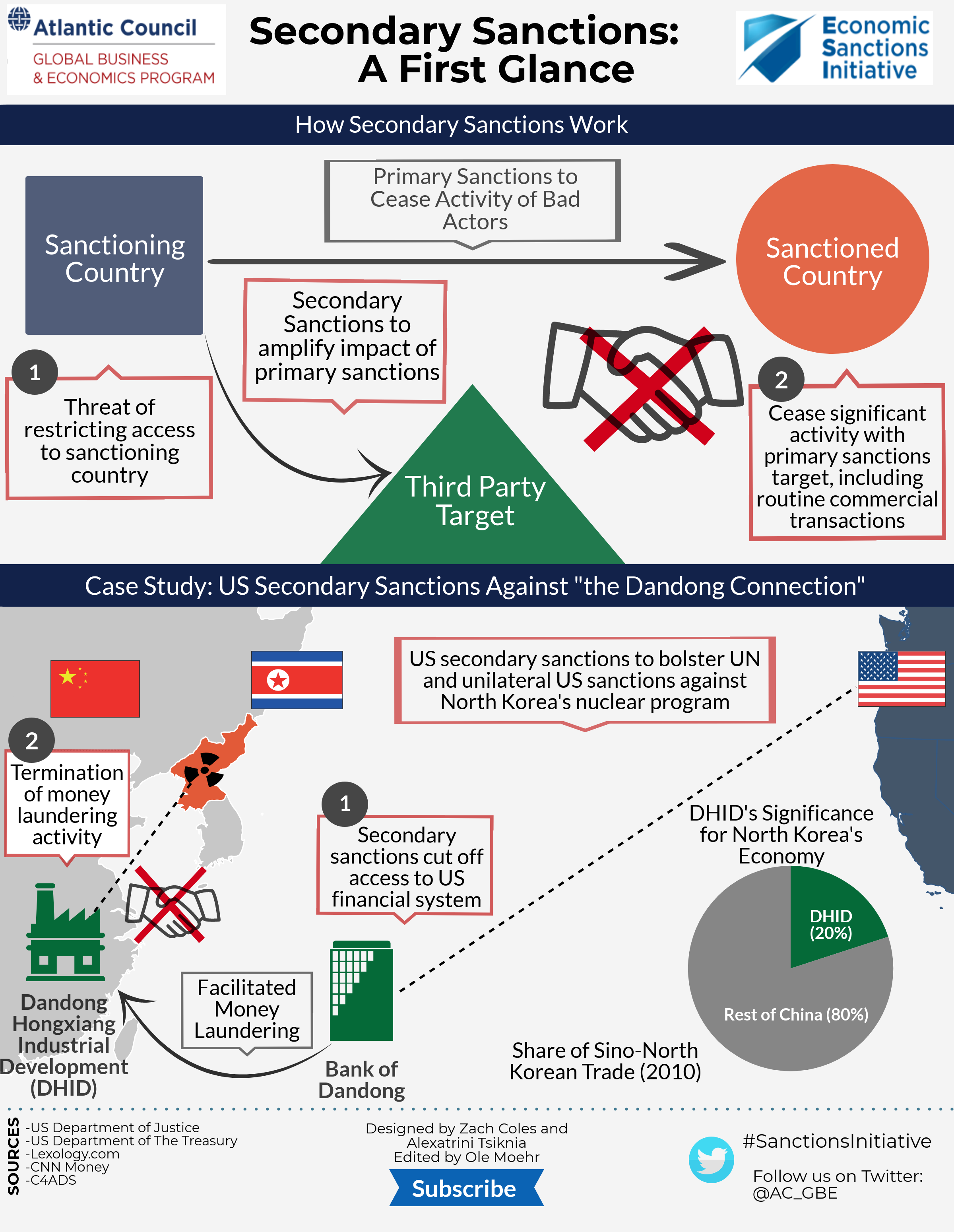

This edition of our EconoGraphic blog explains the difference between primary and secondary sanctions, outlines how secondary sanctions work, and uses a case study to demonstrate how the United States employs secondary sanctions in the real economy.

Primary sanctions, such as asset freezes and trade embargoes, prohibit citizens and companies of the sanctioning country from engaging in certain activities with their counterparts from the sanctioned country. For example, following Russia’s annexation of Crimea, the US government, prohibited, among other things, new investment in Crimea by US persons. Secondary sanctions put pressure on third parties to stop their activities with the sanctioned country by threatening to cut-off the third party’s access to the sanctioning country. Recent US sanctions against Iran illustrate this example well. With the ultimate goal to stop Iran’s nuclear program, US secondary sanctions gave financial institutions around the world a choice to either halt transactions with Iranian banks or lose access to the US financial system. Combined with additional secondary sanctions targeting Iran’s energy sector and broad multilateral support, these financial sanctions succeeded in bringing Iran to the negotiating table.

Secondary and primary sanctions technically function in the same way, in that they are enforced by targeting domestic entities rather than the third party. In the case of the secondary financial sanctions aimed at Iran, the US government prohibited US financial institutions from transacting with designated third-party banks. Put simply, US secondary sanctions legally target US persons and not directly third parties.

Our case study of the “Dandong Connection” underscores how the US government is using secondary sanctions to put pressure on the North Korean government as the regime is continuing develop the country’s nuclear capabilities. On November 2, 2017, the US Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) prohibited US financial institutions “from opening or maintaining correspondent accounts for, or on behalf of, [the Chinese] Bank of Dandong.” In June of 2017, FinCEN had ruled that the Bank of Dandong was violating section 311 of the US Patriot Act by laundering money for the Chinese trade conglomerate firm Dandong Hongxiang Industrial Development (DHID), which, in turn, had run a money laundering scheme for the North Korean government. The US Department of Justice had indicted DHID in 2016 for violating US sanctions by facilitating money transactions for the North Korean regime This is a significant step as the DHID is responsible for a large share of Sino-North Korean trade.

Following its secondary sanctions playbook, the US government made an example of the Bank of Dandong case to deter more significant Chinese banks and financial intermediaries located in other countries from conducting financial transactions with North Korean entities. In the words of Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Terrorist Financing Marshall S. Billingslea in his testimony before the House Foreign Affairs Committee, the imposition of secondary sanctions against Dandong Bank was “the Treasury Department’s first action in over a decade that targeted a non-North Korean bank for facilitating North Korean financial activity [. . . .]. Financial institutions in China, or elsewhere, that continue to process transactions on behalf of North Korea should take heed.”

For a more in-depth look at secondary sanctions, stay tuned for the upcoming issue brief by Atlantic Council nonresident senior fellow John Forrer.