Practice makes perfect: What China wants from its digital currency in 2023

It’s been a year since the Beijing Olympics, where China’s central bank digital currency (CBDC), the e-CNY, debuted in front of an international audience. As the e-CNY network has expanded over the last 12 months, China’s goals have become clearer. Domestically, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) is still in test-and-learn mode, prioritizing experimentation over adoption. Globally, China is less focused on internationalizing the RMB than it is on setting technical and regulatory standards that will define how other countries’ central bank digital currencies will work going forward.

Domestic ambitions

Even with its persistent low adoption rates, the e-CNY is by far the largest CBDC pilot in the world by both the amount of currency in circulation—13.61 billion RMB—and the number of users—260 million wallets. As the pilot regions have expanded to 25 cities, so have the real-world use-cases tested through the pilots. From the start, the PBOC’s objective within its borders has been to not just to compete in China’s domestic payments landscape, which is dominated by two “private” players—AliPay and TencentPay/WePay—but to expand the universe of economic activities that are included the state-enabled payments network. So far, common use-cases being tested include public transportation, public health checkpoints including COVID test centers, integrated identification cards to receive and pay utilities such as retirement benefits and school tuition payments, as well as tax payments and refunds. The pilots have also begun testing technical and programmability functions like smart contracts for B2B and B2C functions, e-commerce and credit provision. Some of these projects are described in the table below..

These domestic test cases are likely to expand this year and cover a broader range of activities and regions. Already, the PBOC is looking to reach the margins of society: e-CNY is being tested amongst elderly populations and in broader rural connectivity schemes initiated to improve digitization. It is also aiming to reach AliPay and TencentPay/WePay customers through integrating their wallet and e-commerce functions for e-CNY distribution. Over the last few years, the PBOC, like the broader Chinese state apparatus, has displayed a tendency toward centralizing regulatory authority when it comes to the two sectors at the intersection of CBDCs —finance and technology. The universe of expanded economic networks enabled by the e-CNY has rightly created concerns regarding the centralization of authority by the PBOC, and the resulting impacts on freedom of choice and from state surveillance for its users. The expanded network of use cases across applications that would collect data on personal identification, health information, and consumption habits and behavior should also raise concerns around the vulnerability of such data to cyber threats domestically and abroad.

Recent developments on regulation

Interestingly, on the regulatory side, at the National People’s Congress in early March, there were a few changes announced to China’s financial regulators. The PBOC has lost its authority over financial holding companies and financial consumer protection regulation to a new regulator, the State Administration of Financial Supervision, which will also oversee banking and insurance regulation. The PBOC is also opening up 31 new provincial-level branches signaling deeper coordination between the PBOC and provincial level authorities. This reshuffle in authority signals further centralization of power under the party apparatus. Unlike other central banks, the PBOC is not fully independent, and requires the State Council to sign off on decisions relating to money supply and interest rates, and the State Council has been tracking PBOC’s research into e-CNY since approving the initial plan in 2016.

From a monetary policy perspective, the e-CNY infrastructure could be a handy tool in the hands of the PBOC, with which it can increase or decrease money supply. As China devises a strategy to stimulate consumer spending this year, there is an opportunity to do so by using and expanding the e-CNY network. China has already increased bank’s short term liquidity by $118 billion and long term liquidity by $72 billion through reducing reserve ratio requirements this year.

PBOC’s ambition for an all-encompassing domestic network of e-CNY infrastructure raises questions about the state’s ability and reach in controlling citizens’ activities. The pilots test real-world scenarios for CBDC use cases, and while adoption has been low, the broad range of applications suggest that testing, not adoption, is the priority for now.

e-CNY around the world

Use of the word “e-CNY” commonly refers to this domestic, retail payments infrastructure. However, much of the discussion in Washington references the cross-border, wholesale capabilities that the PBOC has been testing publicly for a while now. The PBOC participates in a joint experiment with the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, the Bank of Thailand, the Central Bank of the UAE and the Bank for International Settlements named Project mBridge, the purpose of which is to create a common infrastructure across borders to facilitate real-time and cheap transaction settlement. Last October, the project successfully conducted 164 transactions in collaboration with 20 banks across the 4 countries, settling a total of $22 million. Instead of relying on correspondent banking networks, banks were able to link with their foreign counterparts directly to conduct payments, FX settlements, redemptions and issuance across e-HKD, e-AED, e-THB and e-CNY. Interestingly, almost half of all transactions were in e-CNY, which amounted to approximately $1,705,453 issued, $3,410,906 used in payments and FX settlements and $6,811,812 redeemed. Both issuance and redemption transactions were highest in e-CNY, and as stated by the BIS, it was likely because of the automatic integration of the retail e-CNY system and the higher share of RMB in regional trade settlements.

Analysts have characterized wholesale cross-border arrangements like the mBridge as an effort towards de-dollarization and internationalization of the RMB. The e-CNY, much like its physical counterpart, faces the same liquidity constraints due to capital controls on off-shore transactions and holdings. This was reflected in the mBridge experiment, as one of the main feedback from participants was the need for greater liquidity from FX market makers and other liquidity providers to improve the FX transaction capabilities of the platform. Additionally, even if e-CNY were to become freely traded in the future, it could lead to significant appreciation of RMB and balance of payments issues for the PBOC. This is likely not a desirable outcome for the PBOC, which is why currency arrangements like the mBridge can only have a limited impact on the role of the dollar.

If winning the currency competition is an unlikely short-term objective of the PBOC, what has raised national security concerns regarding the e-CNY? China has long used the rhetoric of international cooperation and “do no harm” principles in its cross-border CBDC engagements. However, these cross-border experiments require months of preparation and coordination between central and commercial banks to ensure that regulatory and jurisdictional requirements are aligned. They highlight the need for legal pathways and standards for data sharing, privacy, and risk frameworks between heretofore unsynchronized jurisdictions. Similarly, experiments rely on technological prototypes that interact with existing domestic e-CNY framework, creating de-facto technical standards for cross-border transactions which are likely to be replicated by other jurisdictions. What can potentially emerge is a set of technical and regulatory standards built in the image of the e-CNY, and with that comes the baggage of surveillance and unauthorized access by the Chinese state. MBridge’s platform, for instance, can be utilized for domestic CBDC infrastructure if required by any jurisdiction.

Already, Chinese company Red Date Technology—which, along with China Mobile, UnionPay, State Information Center and others—is behind the creation of Blockchain Service Network (BSN) (a blockchain infrastructure service that connects different payment networks) has launched a similar product under the name of Universal Digital Payments Network. At an event at the World Economic Forum in January 2023, it targeted emerging markets experimenting with CBDCs and stablecoins, since the project wants to build an interconnected global architecture in the vein of BSN’s ambitions.

Technological and regulatory replication by country blocs, enabled by Chinese state and private actors, could create a parallel system of financial networks outside of the dollar, especially where there is a high volume of transactions. The United States relies on the dollar’s dominance to establish global anti-money laundering standards and achieve effective and broad implementation of financial sanctions. The emergence of alternate currency-blocs—enabled by e-CNY-like technology—has the potential to chip away at the primacy of the dollar in global finance and trade, as the dollar will not be the only available option.

Therefore, even though it is unlikely that the development of e-CNY would lead to a broader share of the RMB as a payment or reserve currency, replication of the e-CNY’s technical and regulatory model could further payments infrastructure that is not only inherently unworkable with the dollar, but exacerbates the privacy and surveillance concerns of the retail e-CNY by exporting the problem to the world. China’s domestic motivations of greater control and surveillance, therefore, are intertwined with its global ambitions, and the consequences will be dire in the absence of a competing, privacy preserving, dollar-enabling, payments infrastructure.

Ananya Kumar is the associate director for digital currencies with the GeoEconomics Center.

At the intersection of economics, finance, and foreign policy, the GeoEconomics Center is a translation hub with the goal of helping shape a better global economic future.

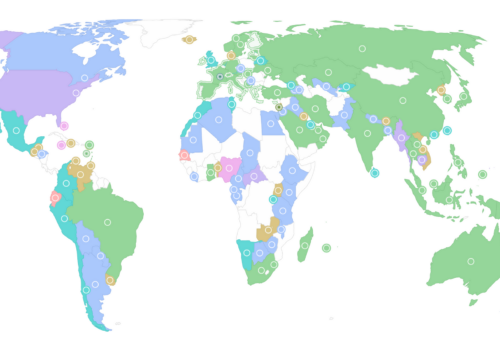

Check out our CBDC Tracker

Further reading

Tue, Mar 1, 2022

A Report Card on China’s Central Bank Digital Currency: the e-CNY

Econographics By Ananya Kumar

China's CBDC, the e-CNY debuted at the world stage during the Olympic Games. Here's what we know so far.

Tue, Mar 21, 2023

Snapshot: Which countries have made the most progress on CBDCs so far in 2023

Econographics By Alisha Chhangani

Despite only being three months into 2023, these 18 countries have made significant progress on central bank digital currencies.

Thu, Dec 15, 2022

It’s official: The United States is developing a bank-to-bank digital currency

New Atlanticist By Josh Lipsky, Ananya Kumar

The New York Federal Reserve’s latest project shows the United States making its presence felt in the digital-currency race.