Breaking down Janet Yellen’s comments on Chinese overcapacity

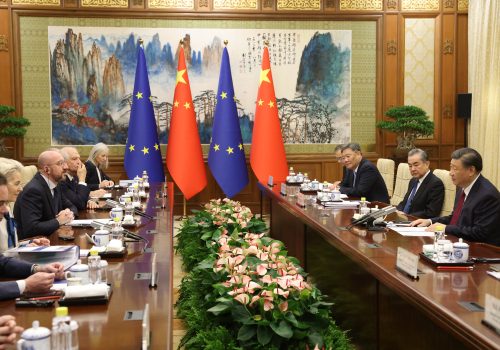

US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has just concluded her visit to China to “manage the bilateral economic relationship,” building on work done by the joint Economic and Finance Working Groups. During her meetings with senior Chinese officials, among other issues, she emphasized the problems of Chinese unfair trade practices hurting US businesses and workers, “underscoring the global economic consequences of China’s industrial overcapacity”. She said that “China is too large to export its way to rapid growth,” and that it would benefit from reducing excess industrial capacity by shifting away from state driven investment and returning to market-oriented reforms that fueled growth in past decades.

The issues Yellen raised reflect real concerns in the United States and Europe—in particular about hi-tech and clean energy sectors like electric vehicles (EVs), lithium batteries, and solar panels. However, it is not a straightforward matter pushing back against China on grounds of overcapacity. The EU has initiated anti-dumping investigation of Chinese EVs—imports of which have surged in many European countries threatening domestic producers—but evidence of overcapacity in that sector is weaker than in solar panels and batteries. Measures to restrict import of these products would simply raise their prices, as Western companies are not in a position to replace Chinese products.

More importantly, the West needs to recognize that overcapacity is intrinsic to China’s economic model—and therefore that calls to end it amount to wishful thinking. In other words, while the complaints about overcapacity are justified from a Western perspective, they will not change the situation any time soon—despite platitudes about US-China relationship being on a “more stable footing” expressed at Yellen’s meeting with China’s Premier Li Qiang.

Chinese EVs pose different challenges than batteries and solar panels

China does have overcapacity problems. Overcapacity is typically measured using utilization rates, the rate of industrial capacity in a sector that is being used for production—low rates imply surplus capacity. Companies with a lot of surplus capacity tend to lower prices to generate demand, hurting the profitability of the whole sector. China has low utilization rates—which have fluctuated around 75 percent, well below the 80 percent considered to be normal. At the end of 2023, China’s capacity utilization rate has recovered to almost 76 percent—a few percentage points higher than the pre-Covid low in 2016 and a few percentage points lower than those of other major countries including the United States (whose utilization rate fell below 80 percent in 2023).

However, behind the aggregate low utilization rate of 76 percent is a very wide dispersion among different sectors. EVs have a high utilization rate, whereas China has very low-capacity utilization rates in low tech sectors such as cement and glass—which are being pulled down by the property construction slump—as well as in lithium batteries and solar panels.

In automobiles, producers of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles have suffered from very low capacity utilization rates—in many cases well below 50 percent—as consumers have been shifting from ICE vehicles to EVs. By contrast, EV producers, especially large ones like BYD, SAIC and Li Auto, have high utilization rates, exceeding 80 percent. These companies have increased their production and export of EVs significantly in recent years, arguably because they are quite efficient in terms of prices and quality. Even Elon Musk admitted that Chinese EV companies “are extremely good…and the most competitive in the world.” The smaller and less efficient EV producers have been weeded out relentlessly from the more than 400 companies launched more than a decade ago to about fifty having some degree of recognized name brands. This consolidation process has accelerated after China ended its subsidy program for EVs at the end of 2022—putting huge pressure on less efficient producers. (While past subsidies supported Chinese EV companies, the fact that this subsidy has been ended could be used by China in its defense against the EU investigation.)

Furthermore, China is not as dependent on the export of automobiles including EVs as some other major car manufacturing countries. Specifically, its export rate is quite low, at 15 percent compared with 48 percent in Japan, 72 percent in South Korea, and 79 percent in Germany. As a result, possible EU and US tariffs may blunt China’s EV export growth in those regions but can hardly be expected to alter the overall growth trajectory of the country’s EV sector.

In the first two months of 2024, China experienced an 8 percent increase in total EV export in volume terms, having been able to shift EV sales in the EU (which has declined by 20 percent) to Asia (export to RCEP countries has increased by 36 percent). These two regions account for 30 percent each of China’s EV export. Furthermore, China can boost domestic demand by raising the target for the share of EVs in new car sales from 45 percent by 2027 (rather low relative to the target of 65 percent by 2030 in the EU). Such a move would be helped by the fact that China has rolled out 2.7 million charging stations across the country at the end of 2023–compared with only 64,187 in the United States.

In contrast to the EV sector, lithium battery and solar panel producers have suffered from very low capacity utilization rates—in many cases below 50 percent. In particular, China’s annual production of solar panels is more than twice the global demand. This huge overcapacity has significantly driven down the prices of these products, benefiting all importing countries in their green transition efforts. Raising tariffs on these products will increase their prices to users and delay many countries’ green transition targets, especially as Western companies are not in a position to replace Chinese products. It is instructive to note that President Biden has vetoed a Congressional resolution to reinstate tariffs on cheap solar panel imports from South East Asian countries—for fear of delaying the pace of solar installations necessary to meet his administration’s target of 100 percent clean electricity by 2035.

Overcapacity is intrinsic to China’s economic system

The West should focus its complaints on the sectors where Chinese overcapacity is most egregious—for example in wind power turbines on which the European Commission has just launched an anti-subsidy probe. As it does so, it must also recognize that the long cycle of overcapacity build-up and correction is generic to China’s economic system of state capitalism. Strategic decisions by leaders the Communist Party of China (CCP) will mobilize resources to invest in chosen sectors. That leads to overcapacity, which comes with unfavorable side effects, which eventually cause the leadership to undertake corrections. This process usually takes far longer than the prompt market-driven resolution of inefficient and unprofitable companies in the West. In China, grossly inefficient companies have been liquidated or absorbed by more efficient units, but in a managed and gradual consolidation process to minimize undesirable social impacts such as rising unemployment or hollowing out manufacturing communities.

A clear example of China’s overcapacity cycle can be found in the huge stimulus program unleashed by Beijing in response to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis—offering abundant and cheap credit to spur construction in infrastructure and housing. The resulting overcapacity in coal, steel, and other construction materials was quite severe, depressing producer price inflation, keeping it in negative territory for more than fifty consecutive months. In addition, overcapacity in the steel industry caused bitter complaints by other steel producing countries. By 2015, China launched a wide-ranging Supply Side Structural Reform to reduce overcapacity by encouraging a consolidation process in those sectors, cushioned by measures to boost demand. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013, could have been designed partly with the goal of exporting the country’s surplus capacity in construction in mind. These measures were able to bring the overcapacity problem under some degree of control.

In another example, China has had significant overcapacity in the shipbuilding sector, which is 232 times greater than that of the United States, posing a threat to competitors like South Korea and Japan. China has addressed that problem in a strategic way by using its abundant capacity to build modern warships to catch up with the US Navy.

At present, CCP leadership seems to be aware of the industrial overcapacity problem which has caused producer price inflation to be negative continuously since late 2022. In presenting the government work program at the National People’s Congress meeting last month, Premier Li Qiang said that “China wanted to reduce industrial overcapacity” but flagged more resources for tech innovation and advanced manufacturing to develop “new productive forces.” It appears that, like in the 2015 episode, China will spur the consolidation of the sectors having significant surplus capacity. However, the result could be more efficient and competitive enterprises, continuing to pose a challenge to producers in the West and a few developing countries aspiring to develop their manufacturing industry.

A realistic path forward

The United States and EU, together with other manufacturing nations, have wrestled for some time with the overcapacity problem in various industries, caused by China’s economic system of state support to its enterprises. So far, the major remedy to this challenge has been countervailing duties on China, either sanctioned by the World Trade Organization (WTO) after a lengthy and difficult process or imposed unilaterally by former President Trump and maintained by President Biden. However, raising tariffs has not been a totally satisfactory solution. It has given some protection to impacted sectors in importing countries at the cost of higher prices to consumers. But it has not been a game changer in terms of ensuring a level playing field for all countries.

Based on historical experience, it’s safe to say the current phase of China’s overcapacity in hi-tech and green industries like lithium batteries and solar panels will be impacting the rest of the world for some time to come. It is reasonable to criticize and complain to China, but policymakers should remember that an end to overcapacity would mean a major shift in China’s economic model, which is exceedingly unlikely. They must therefore be prepared for a sustained period of heightened trade tension during which Beijing will eventually take some measures to reduce industrial overcapacity when its domestic impact becomes unacceptably negative—but in China’s own way and on its own timeline.

Hung Tran is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council GeoEconomics Center, a former executive managing director at the Institute of International Finance and former deputy director at the International Monetary Fund.

Further reading

Thu, Mar 7, 2024

Unpacking China’s 2024 growth target and economic agenda

Econographics By Hung Tran

At the opening of China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) Premier Li Quang delivered his first Government Work Report, setting the key economic and social policies and targets for this year.

Mon, Dec 11, 2023

China’s manufacturing overcapacity threatens global green goods trade

Econographics By Niels Graham

Chinese lending is exacerbating a growing glut in its green manufacturing sector. Beijing is increasingly looking abroad to absorb excess capacity. This may have devastating effects for the global trading system as economies move to protect their own domestic industry.

Wed, Jan 10, 2024

China’s local government debts are coming due

Econographics By Jeremy Mark

China's economic slowdown brings local government debts into sharp focus, threatening infrastructure and social services.