China’s manufacturing overcapacity threatens global green goods trade

Chinese lending is undergoing a deep, structural transition away from the property sector to support manufacturing. The shift is generating serious fears of overcapacity and will likely accelerate the fractionalization of the global trading system as countries move to protect their own industry.

In just under four years Chinese banks have gone from providing its domestic property sector with over one trillion dollars in new annual lending to a net decline in outstanding debt—for the first time since the PBOC began keeping track in 2005. Instead, Chinese banks are facilitating massive new borrowing for Beijing’s manufacturing sectors. In Q3 2023 Chinese banks extended nearly $700 billion in new loans—often lent at below-market interest rates—to the sector from the previous year. Across China, new factories producing electric vehicles (EVs), batteries, and other products integral for the green transition are springing up. However, with a saturated manufacturing sector and Chinese domestic consumption sitting near an all-time low, Beijing is now looking abroad to absorb this new production. These trade flows will exacerbate the tense trading relationship it has with economies like the United States and EU who are also fostering domestic industries and jobs producing many of those same products.

This is not the first time Chinese overcapacity has caused anxieties in the US and EU over green energy manufacturing. A decade earlier a similar debate focused squarely on Chinese solar panel exports was playing out in Brussels and Washington. In 2007, 30 percent of global solar cells were produced in the EU, and a smaller but growing share in the United States. Unfortunately, the 2008 financial crisis and a new industrial policy effort led by Chinese local government subsidies quickly began eating away at Western companies’ market share. To protect their domestic industry, in 2012 the EU announced an anti-dumping investigation resulting in tariffs of 47 percent. In turn, China threatened to retaliate with tariffs on key European exports, forcing the EU to back down. They instead imposed a price floor. This was insufficient. China now dominates global solar panel production. In 2021, China made up just 36 percent of global demand but was responsible for well over three quarters of global solar production.

Will Chinese lending toward manufacturing be a replay of this same dynamic? There is reason to believe this time could be different. Shifting views on China make Brussels less likely to capitulate to retaliatory threats from Beijing. China’s surge in manufacturing support coincides with similar efforts by both the United States and EU through programs such as the Biden Administration’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) as well the European Commission’s Green Deal. The scale of these endeavors are magnitudes greater than support each government provided to the solar industry a decade earlier, further incentivizing action by western capitals to defend priority industries.

While promoting clean energy and addressing climate change remain the goals of the IRA and Green Deal, they go hand-in-hand with US and EU efforts to reshore domestic manufacturing capacity for solar and wind power equipment, batteries, heat pumps, electrolysers, and fuel cells. Both governments have emphasized the importance of their respective green transitions being supplied in large part by their domestic manufacturing sectors, not low-cost foreign suppliers like China. US and European initiatives should be thought of just as much as a jobs creation and manufacturing revitalization pushes as a green economy effort.

However, while existing policies have insulated the US economy and de-risked its supply chains from Chinese imports, lack of EU action means that its markets have become increasingly dominated by cheap green technology imports from China. If the EU wants to avoid the fate of the global solar industry, its window to take action is steadily declining.

The tension over who manufactures the green transition is already playing out in EVs. Over the past three years Chinese exports of EVs have surged more than 1500 percent. While high tariffs (27.5 percent for auto imports from China) as well as local content requirements have prevented this influx from reaching the United States, strong demand, low tariffs, and purchasing subsidies have made the EU a prime destination.

From January to October 2023 the EU bought $12 billion or 42 percent of all Chinese EV exports. The influx of cost-competitive vehicles are now threatening Europe’s own emerging EV production. To respond, in October, the European Commission launched an anti-subsidy investigation into imports of Chinese made passenger battery electric vehicles. If the Commission is able to prove that its industry is directly threatened by Beijing’s countervailable subsidies, it can then move to impose tariffs above the standard 10 percent EU rate for cars.

EVs, however, may just be the start of a series of trade disputes and investigations to determine China’s prevalence in most clean energy supply chains. It’s possible European Commission inquiries into wind turbines, heat pumps, and electrolyzers could be next. In October, Didier Reynders, the EU’s acting Commissioner for Competition, suggested Chinese turbine exports may merit a similar investigation. Like EVs, China’s wind sector has received generous subsidies and exports have surged in recent years. Since 2015, Chinese manufacturers have grown from supplying around 3.5 percent of global exports to 20 percent in 2022. This growth is of particular concern for Brussels because a larger share of these increased exports are making their way into the European market. In 2018, the EU purchased 21 percent of Chinese exports of wind turbines and their related parts. By 2023 this share had jumped to nearly 29 percent.

The United States, in contrast, has effectively reversed this trend. In 2018, China sent around 20 percent of its wind exports to the United States. By 2023 the US’ share had fallen to just over 7 percent. This divergence in import share can be explained by a combination of declining US demand as well as new producers from Spain, India, and Germany entering the market. These alternative manufacturers were more easily able to divert US market share from China because tariffs implemented under the Trump administration during the US-China trade-war make Chinese exports more expensive in the US market than the EU market.

Chinese exports of electrolyzers and heat pumps are also drawing attention from the European commission. This is for good reason. Over the past decade China’s share of global exports for electrolyzers has grown 10 percentage points to control 26 percent of global exports. Similarly, heat pumps have grown 14 percentage points with Chinese manufacturers encompassing 20 percent of global exports. Though its share is declining, the EU remains the primary destination for Chinese heat pumps with nearly 69 percent of Chinese exports traveling to EU member states in 2023. Beijing’s subsidized cost structure could increasingly challenge the EU’s own robust heat pump manufacturing sector.

Though the EU currently makes up a far smaller portion of Chinese electrolyzers exports, that could quickly change. China’s state-led development of the sector has resulted in significant overinvestment in electrolyzer manufacturing capacity which now far exceeds short-term demand. China now has electrolyzer productive capacity four times what is required by global demand.

China’s green technology exports are rapidly rising. As Beijing expands its bets on manufacturing and export-oriented growth, it is positioning itself as the global factory supplying all aspects of the green transition. So far Trump-era tariffs and stringent domestic continent requirements have insulated the US market—though this could change as the benefits of cheap lending filter through to export prices. The EU has been less lucky. If Brussels and Washington want to avoid the fate their solar industries experienced a decade earlier, they must deeply scrutinize Chinese exports of EVs, wind turbines, heat pumps, electrolyzers, and other similar products. If China is unwilling to reduce its own supply, western capitals may be forced to restrict foreign access to their markets. While this may save their own industries, new interventions will further fractionalize the global trading system.

Niels Graham is an associate director for the Atlantic Council GeoEconomics Center where he supports the center’s work on China’s economy and US economic policy.

At the intersection of economics, finance, and foreign policy, the GeoEconomics Center is a translation hub with the goal of helping shape a better global economic future.

Further reading

Wed, Oct 4, 2023

Running out of road: China Pathfinder 2023 annual scorecard

Report By

The China Pathfinder project examines whether China’s economy is converging or diverging with the world's leading open market economies.

Tue, Dec 5, 2023

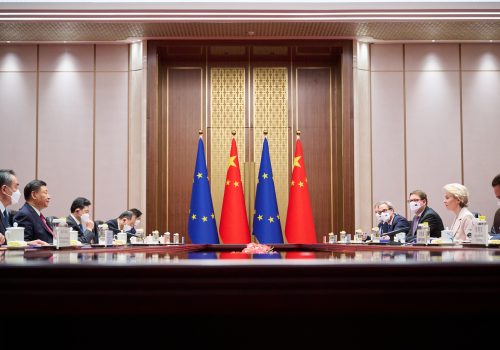

Don’t expect much from the EU-China summit

New Atlanticist By Colleen Cottle, Jörn Fleck

If this week's summit does prove to be as empty as anticipated, this should spark the EU to rethink its approach to these meetings.

Thu, Apr 20, 2023

The US is relying more on China for pharmaceuticals — and vice versa

Econographics By Niels Graham

US China trade of pharmaceutical and active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) is rapidly increasing. Supply chain mapping will be key to risk management