On June 15, 2017, US President Donald J. Trump issued Executive Order 13801, which sought “to promote affordable education and rewarding jobs for American workers” by increasing the number of apprenticeship opportunities. Trump’s stated goals are ambitious. With a proposed ApprenticeshipUSA budget of $200 million (roughly double the previous amount), the president wants to increase the number of US apprenticeships from 505,000 in 2016 to 5 million by 2022.

Several factors help explain the growing appeal of apprenticeships as a policy proposal. To begin with, the costs of a college education continue to skyrocket. In the past twenty-five years, the average annual tuition and fees at a private nonprofit four-year institution has grown by 93.08 percent (even after adjusting for inflation). Additionally, automation in manufacturing, retail, resource extraction, and other blue-collar industries produced significant job losses by rendering once-essential roles redundant. Those jobs that remain often require more trained skills than the newly unemployed possess, thereby creating a “skills gap” between job applicants and prospective employers.

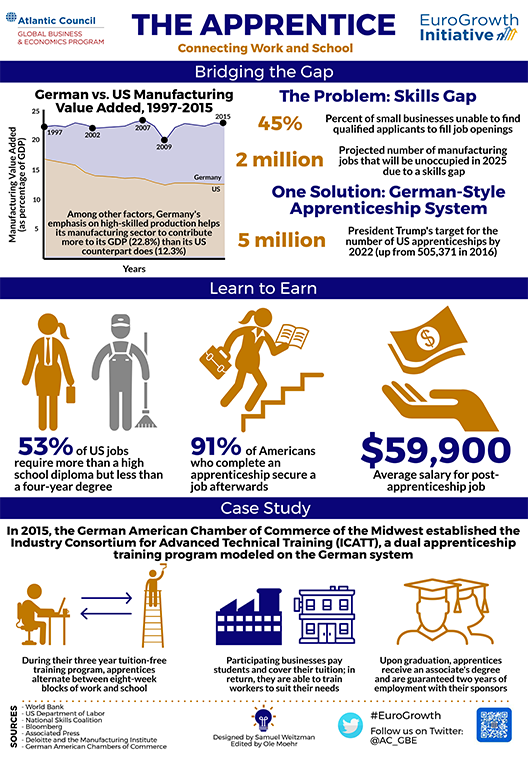

The manufacturing sector demonstrates the seemingly paradoxical implications of the skills gap, whereby some firms simultaneously reduce hiring and yet struggle to find workers. Even as manufacturing employment continues its decades-long decline (having shrunk by 35.72 percent since January 1980), hundreds of thousands of jobs in the industry remain unoccupied. By 2025, as many as two million US-based manufacturing jobs could be unfilled due to a lack of sufficiently skilled workers.

In light of these challenges, apprenticeships are seen as one way to bridge the skills gap. Individuals who want good jobs are matched with companies looking for dependable workers with particular sets of skills. Filling the skills gap with well-trained apprentices may also improve the competitiveness of US companies. In the United States, the most-cited model for job training is Germany, whose apprenticeship programs help to close potential gaps between job-seeker’s skillsets and employer’s needs. Comparing the two economies underscores Germany’s superior ability to train its workers, particularly in the realm of manufacturing. On a percentage-of-gross-domestic-product (GDP) basis, for example, German manufacturers contribute more to GDP (22.8 percent) than their American counterparts do (12.3 percent).

In recent years, the US subsidiaries of a number of large German manufacturers—including Volkswagen, BMW, Siemens, and Grenzebach—have brought their apprenticeship programs with them across the Atlantic. In turn, some US-based small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have created their own programs modeled on their German counterparts. One successful example is the Illinois Consortium for Advanced Technical Training (ICATT), in which the German American Chamber of Commerce of the Midwest partners with six community colleges and thirty businesses to match prospective workers with employers offering free tuition, paid apprenticeships, and full time jobs after graduation. Moreover, US apprenticeship programs are not limited to fields traditionally associated with job training like manufacturing and construction. Indeed, multiple major technology, insurance, and financial services firms that operate in the United States—including Microsoft, IBM, JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, Zurich North America, and Aon—have already begun to embrace a skills-based approach to hiring that prioritizes vocational training over traditional four-year degrees.

To be sure, apprenticeships cannot solve all of the problems facing the US economy. If, or rather when, advances in technology render certain vocational skills redundant, former apprentices-turned-workers may struggle more to find employment later in life than their college educated counterparts. For this reason, apprenticeships may be better understood as one part of a larger societal shift towards lifelong learning.