Three challenges in cryptocurrency regulation

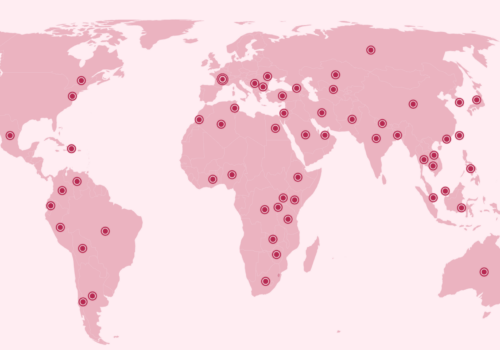

Around the world, policymakers and regulators are hurriedly writing, adopting, and amending crypto-asset regulations. Nearly three-quarters of the countries surveyed in the Atlantic Council’s Cryptocurrency Regulation Tracker are exploring changes to their regulatory framework—and many of those changes are substantial. At the global level, India has made crypto-asset regulation a major goal of its G20 presidency. And, here in the United States, the legal fallout from the collapse of FTX continues apace—earlier this week, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) sued Binance and Coinbase, two major crypto exchanges and FTX rivals.

Policymakers who recently gathered in Washington, DC for the Spring Meetings of the IMF and World Bank highlighted the need for global progress on crypto-asset regulations. G20 finance ministers and central bank governors included global regulatory development on their list of priorities, as did the International Monetary and Financial Committee. Crypto regulations were discussed throughout the meetings, including in a session focused on the future of crypto-assets.

The meetings made two things clear. First, the need for robust, globally coordinated crypto regulations is evident. And, second, policymakers face substantial challenges achieving that goal. Following on discussions held at the Spring Meetings, we used our Cryptocurrency Regulation Tracker to identify several of the major policy dilemmas facing policymakers and regulators.

Consumer protection rules are lagging behind other forms of regulation

Consumers participating in crypto-markets are exposed to considerable risk. Theft is increasingly common. Volatility, often fueled by speculation, is a defining feature of crypto markets. And misinformation and deceptive advertising make informed investing difficult. Despite the risks that consumers face, we found that only one-third of the countries studied had rules in place to protect consumers. Other countries may have legal protections that extend to crypto market participants, though the law is often untested or ambiguous.

Fortunately, countries that do provide consumer protections are demonstrating a diversity of approaches. India, France, and others have helped consumers make better informed decisions by requiring that advertisers disclose risks associated with crypto-investing. In South Korea, crypto-asset service providers, such as exchanges and wallets, are required to obtain an information security certificate from the Korea Internet and Security Agency, decreasing the likelihood of theft. And many countries, including Australia and Japan, have rules in place to prevent and penalize deceptive conduct and fraud. While these examples demonstrate steps some countries are taking, the safety of crypto markets requires that policymakers redouble efforts to enact consumer protection regulations.

Regulations to prevent another FTX-style collapse are a long way off

Centralized exchanges like FTX and Binance play a critical role in the crypto ecosystem. By allowing individuals to participate in “off-chain” transactions involving crypto-assets, they dramatically reduce the barriers to entry posed by more technically complex “on-chain” transactions. The substantial gains made in market capitalization and adoption would be unlikely absent centralized exchanges.

But centralized exchanges that perform multiple functions pose risks that regulators must address. Many exchanges are not sufficiently transparent about their operations, finances, or governance, leaving investors in the dark on key matters. Some companies are taking steps to address this problem by disclosing “proof of reserves”, a transparent accounting of a company’s assets and liabilities. While more than half of the countries in the tracker have licensing or registration rules, these do not typically include disclosure requirements.

Centralized exchanges may misuse customer funds. Unlike in traditional finance, where customer funds are subject to certain protections, centralized exchanges typically face either nonexistent or less stringent regulations. The Cryptocurrency Regulation Tracker includes only two examples of a specific requirement that crypto companies segregate customer funds, placing a firewall between customer money and proprietary trading. The European Union’s Markets in Crypto-assets framework, which became law last month, has specific rules that wall off customer funds from proprietary trading. The US Securities and Exchange Commission is considering a similar move.

In some cases, global exchanges may fall outside national or regulatory borders. This leaves policymakers incapable of performing basic oversight, as was the case with FTX in the United States. Policymakers have yet to achieve coordinated global action and are continually confounded by crypto companies that evade—intentionally or otherwise—traditional regulatory definitions. Bringing crypto activity within the regulatory perimeter remains a key challenge.

Our research shows that more needs to be done to prevent the next FTX. Fortunately, that debacle has propelled policymakers and regulators to fill this perilous gap.

Low- and middle-income countries lag advanced economies in regulatory development, but not in rates of crypto adoption

The Cryptocurrency Regulation Tracker considers four categories of regulation: taxation, anti-money laundering, consumer protection, and licensing. Of the advanced economies we reviewed, 64% have regulations in each of these categories. Only 11% of the middle income countries have rules in all four categories, and none of the low-income countries do. These findings identify a clear trend: low- and middle-income countries are adopting crypto-regulations more slowly.

Limited regulatory development, however, has not slowed adoption. In fact, our research found virtually no relationship between crypto-regulation and adoption rates. Six of the ten countries with the highest rates of adoption (according to Chainalysis) have in place either a partial or general ban on crypto-assets. It is worrying that some low- and middle-income countries, who may be vulnerable to crypto-induced shocks, have active crypto-markets with few regulations.

The widening regulatory gap between countries is a critical challenge for international financial institutions and standard-setting bodies. Patchwork, uncoordinated global regulations present opportunities for regulatory arbitrage. Companies may consider issuing new crypto-assets from jurisdictions with few or no guidelines and selling those assets to investors around the world—even in countries where such sales are technically illegal. In the short-term, such activity could hurt consumers and facilitate illicit activity. In the longer-term, it could present a meaningful financial stability risk.

In recent remarks at the Atlantic Council, World Bank President David Malpass urged regulators to make global standards “accessible” to countries with lower state capacity. Indeed, the International Monetary Fund, Financial Stability Board, and others must do the tough work of both establishing global standards and providing technical assistance where needed.

Regulators around the world face multiple challenges. They must protect customers and put in place safeguards to prevent the next FTX-style collapse, all while coordinating across diverse jurisdictions. And they have a long way still to go.

To keep up with this rapidly evolving topic, follow the GeoEconomics Center’s Cryptocurrency Regulation Tracker.

Greg Brownstein is a Bretton Woods 2.0 Fellow and research consultant with the GeoEconomics Center.

At the intersection of economics, finance, and foreign policy, the GeoEconomics Center is a translation hub with the goal of helping shape a better global economic future.