On April 17 2019, US Secretary of State Michael Pompeo announced an important change in the United States’ policy toward Cuba: Title III of the Cuban Liberty and Democracy Solidarity Act of 1996 (LIBERTAD Act) would no longer be suspended. As a result of this decision, US claimants can now seek compensation for property confiscated by the Castro government. The move has important implications for US and foreign companies doing business in Cuba. This edition of the EconoGraphic explains the history and purpose of the LIBERTAD Act, evaluates the policy’s potential impact on US allies’ economic interests in Cuba, and highlights its implications for the pressure campaign against the Maduro regime in Venezuela.

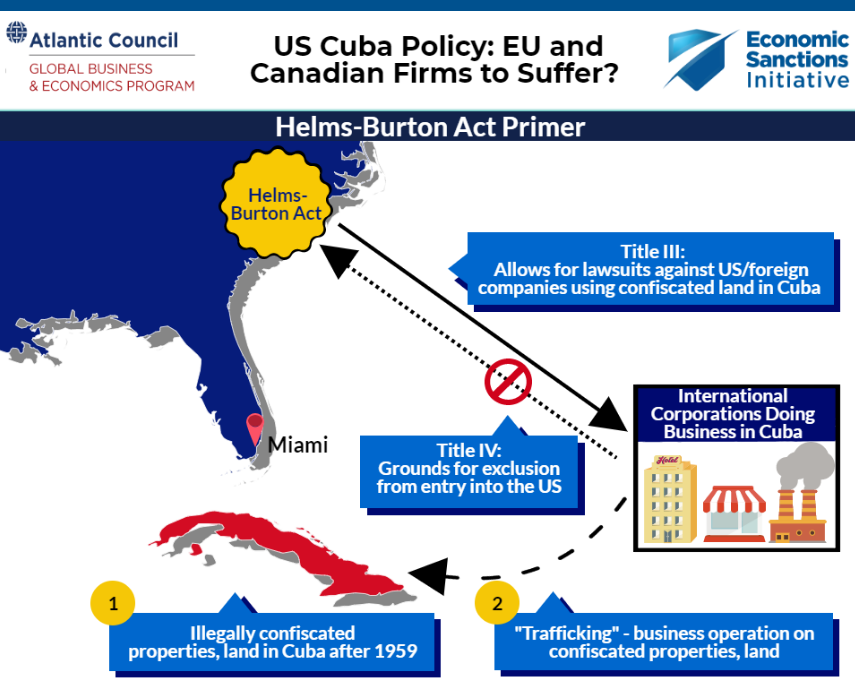

Congress passed the LIBERTAD Act—also known as the Helms-Burton Act—in 1996, to bolster the US embargo against Cuba. President Clinton signed the LIBERTAD Act into law that same year but decided to waive the law’s Title III following strong pushback by the European Union (EU), Canada, and others. Title III enables US citizens whose property was confiscated by the Castro regime to file lawsuits against entities or individuals that currently use these properties. The EU, Canada, and others consider Title III to be an unlawful extraterritorial application of US law. In response, the EU also created a “Blocking Statute” that prohibits enforcement of related US legal decisions within the EU, allowing EU companies sued in the US to recover any damages incurred. Partly because of this strong opposition from key US allies, administrations to-date have decided to waive Title III—until the policy reversal last April. Immediately following the decision, EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini voiced “serious concerns”, announcing the EU would consider making use of its Blocking Statute to protect European businesses from US lawsuits. Spain’s Foreign Ministry further argued that “the extraterritorial application of the legislation is contrary to International Law (…) without giving rise to any advantage either for the US claimants or for the Cuban population as a whole”. Both the EU and Canada intend to pursue action through the World Trade Organization to protect their exposed firms, mostly those in the tourism and mining sectors.

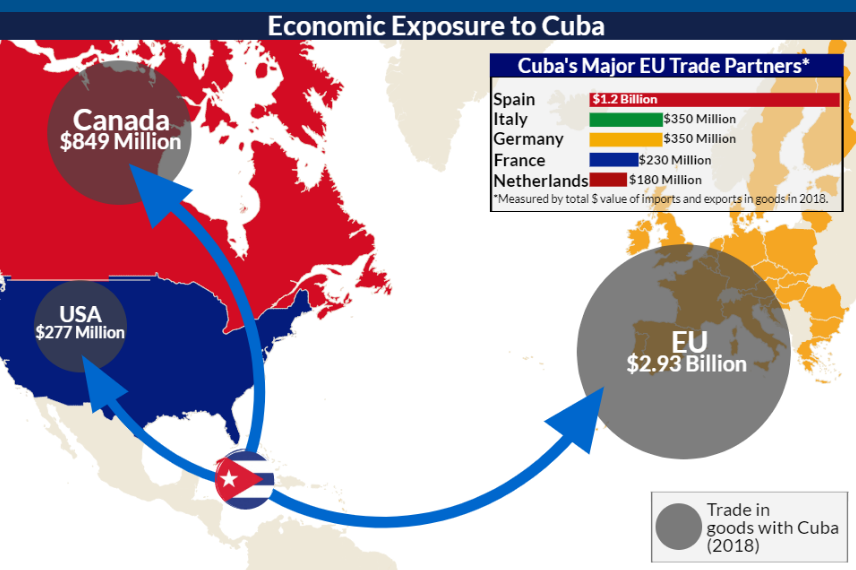

Since 2014, Cuba has begun to gradually open its economy to foreign investors, due in part to its Law No.118 (known as the “Foreign Investment Law”). Foreign companies subsequently flowed in rapidly with investments in the island, typically through joint enterprises and International Economic Partnership Agreements. Today, the EU is Cuba’s main export partner and its biggest foreign investor. Spain in particular has deep economic ties with Cuba, especially in the tourism industry—one of the main sources of revenue for the island. Spain ranks as Cuba’s second largest trade partner, below only China. Likewise, Canadian firms have been longstanding active investors in Cuba, specifically in the energy and mining sectors, and are also facing potential ripple effects from Title III activation. Canada’s bilateral trade with Cuba reached a five-year high of C$1.17 billion in 2018. While the overall risk to these countries’ economies is relatively small, the potential costs for the exposed firms are high.

By attempting to isolate Cuba from foreign capital and investment, the Trump Administration hopes to squeeze its economy and pressure the regime in Havana. Whether this policy will bring about the desired change in the human rights situation on the island remains to be seen. The activation of Title III alone is unlikely to bring regime change in Cuba. Evidence from the half-century embargo shows that unilateral sanctions as a means of driving political change have proved insufficient on their own, while simultaneously alienating economic allies.

Furthermore, activating Title III may undercut other important US policy goals in the region, such as putting an end to Maduro’s rule in Venezuela. The success of the US-led pressure campaign there depends upon unity among the anti-Maduro coalition, of which Canada and the EU are vital members. Both have imposed sanctions, export embargos and travel bans against Maduro officials alongside the United States. Notably, Spain plays an important role in Venezuelan affairs, given its close economic, cultural, and diplomatic ties, granting Spain and outsized influence on the EU position in the matter. Spain could play a central role, for instance, in hardening visa restrictions on Maduro’s associates and family. Penalizing Spanish firms operating in Cuba therefore risks undermining US-Spanish relations at a time when cooperation is necessary. By straining already tense relations with its allies over Cuba, the United States risks distracting itself and partners from objectives at hand in Venezuela, while failing to make any progress in Cuba.