On June 8, the United Kingdom will vote in its second general election in just over two years. The last election in May 2015 resulted in a Conservative government, and led to the June 2016 national referendum on Britain’s membership in the European Union. Following the result in favor of Brexit, Prime Minister David Cameron—the leader of the unsuccessful Remain campaign—resigned, and former Home Secretary Theresa May took office.

May’s leadership has been dominated by Britain’s departure from the EU, and the implications for the country. In April, facing domestic opposition to this approach, including legal challenges, she called a snap general election. She argued this would help Britain have a stronger negotiating position in the talks with other EU member states, and would give her a clear mandate to go ahead with leaving the EU. Although Brexit is an important issue in the election, however, it is not the sole focus of the campaign. Health, education, welfare, immigration, and the environment feature heavily in the manifestos of the major parties.

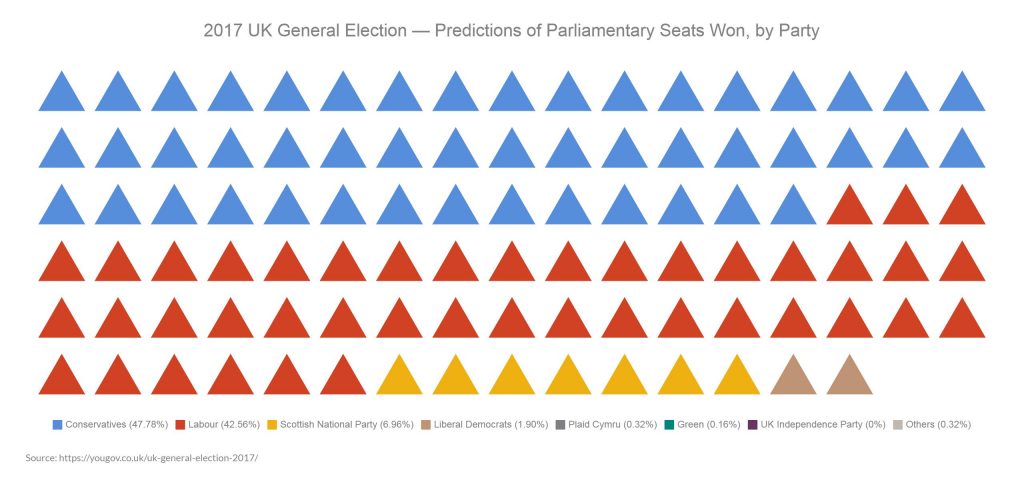

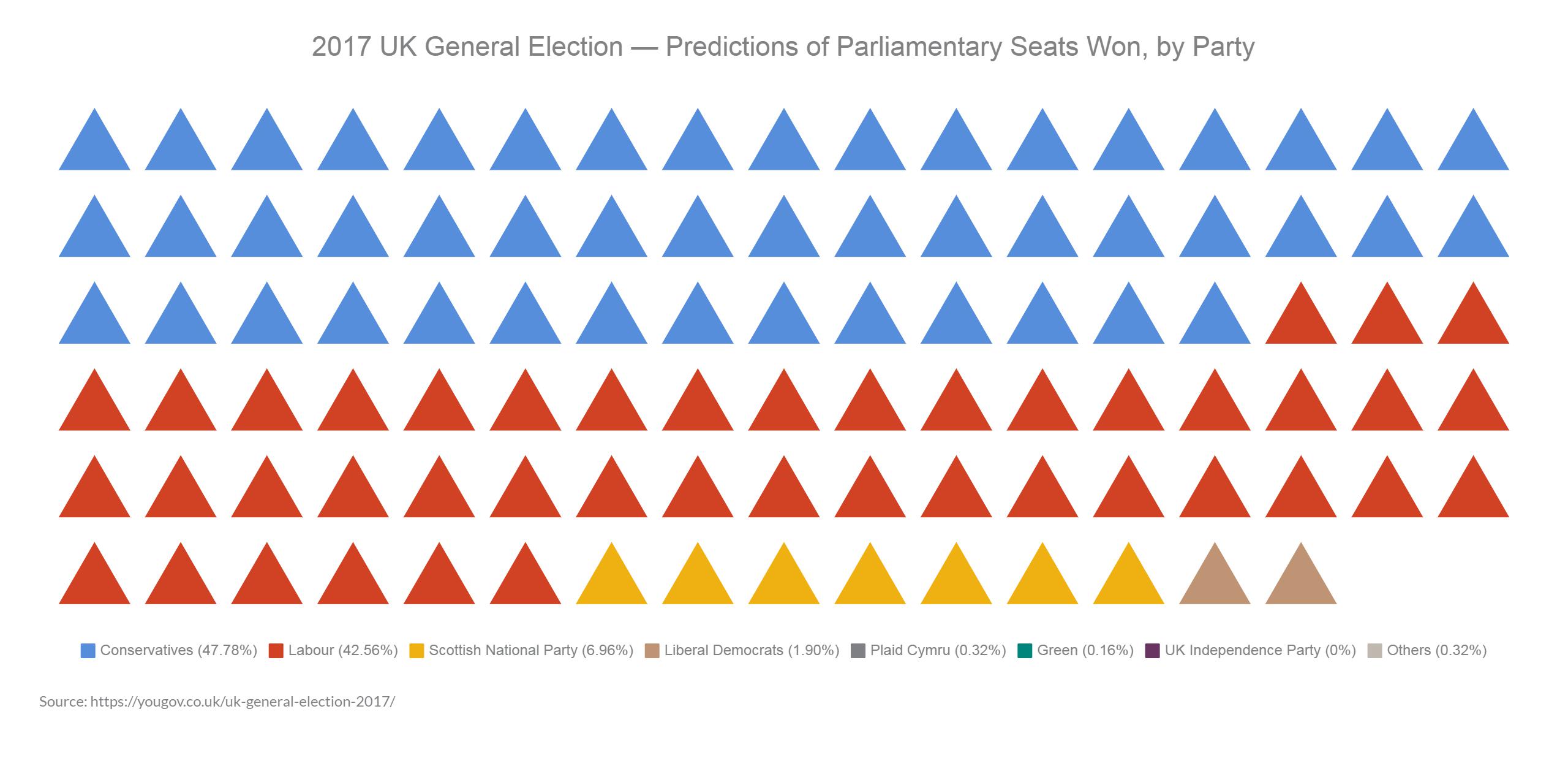

Six major parties are contesting these elections, with the Conservative and Labour Parties holding the largest share of seats.

- Conservative Party: The current, center-right governing party has stated that “Brexit means Brexit,” and has moved toward a hard Brexit, which would remove the UK from the single market and customs union, and reduce freedom of movement.

- Labour Party: The main opposition party has moved increasingly to the left under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn. Labour has accepted the result of Brexit, but wants to redesign the negotiation strategy, and retain commitment to the single market and customs union.

- Liberal Democrats: Sitting on the center-left of the political spectrum, the Liberal Democrats lost heavily in 2015 following their time in coalition government. They have pledged a second referendum on Britain’s membership in the EU, once the terms of the negotiation have been made clear. They remain committed to the EU single market, customs union, and freedom of movement.

- Scottish National Party (SNP): Based in Scotland, SNP is another left-of-center party. Keen to remain part of the EU, leader Nicola Sturgeon has promised to hold a second referendum for Scottish independence if Brexit goes ahead.

- UK Independence Party (UKIP): UKIP’s central aim has traditionally been to push for the UK to leave the EU. While its support base has diminished dramatically since 2015, the party wants to further restrict immigration, arguing there is a problem with integration in the UK.

- Green Party: The Green Party supports a second referendum on Brexit once the terms of leaving are known, and calls for more progressive alliances between parties of the left and center, to counter the likelihood of an overwhelming Conservative majority.

This is a period of change, uncertainty, and opportunity for the UK. The country has had significant elections in each of the past four years: the Scottish independence referendum (2014), a general election (2015), the EU referendum (2016), and now a new general election. Despite their frequency, elections are not necessarily addressing the root causes of dissatisfaction and division within society, including the state of the economy, rising unemployment, and growing inequality. The decision to leave the EU only compounds many of these problems, due to the instability and uncertainty it has produced.

Changes in political leadership have accompanied these elections. After the 2015 vote, the leaders of Labour, the Liberal Democrats, and the UKIP resigned. The surprise appointment of outside candidate Jeremy Corbyn in Labour, and uncertainty within his party over his suitability for leadership, has led to a weak opposition in British politics, limiting the potential to hold the government to account and temper some of its policies. If May’s Conservative Party were to achieve a sizeable majority, it would help her party pass the legislation required for Brexit, while significantly weakening the opposition for the next few years.

Although Conservatives are expected to win a majority in June, local elections have shown the potential for a political surprise. Recent polls have revealed an increase in support for Corbyn, significantly narrowing the Conservative’s poll lead. Though polls have proved wrong, if May does not command a significant majority, it will weaken her within her party and undermine her national and Brexit agendas. If Labour does make gains, it will strengthen Corbyn’s hand as the leader of the left, and reinforce support for the political agenda he promotes. A revived Labour could lead to a reconsideration of the Brexit negotiating terms, softening the impact of departure. Such an outcome may also create more space for a stronger center ground between the two parties. There is talk of a potential hung parliament, but such an outcome appears unlikely, given the UK’s first-past-the-post electoral system. In such circumstances, a more left-wing alliance may emerge based on support for specific issues, such as a softer Brexit and improving the health service.

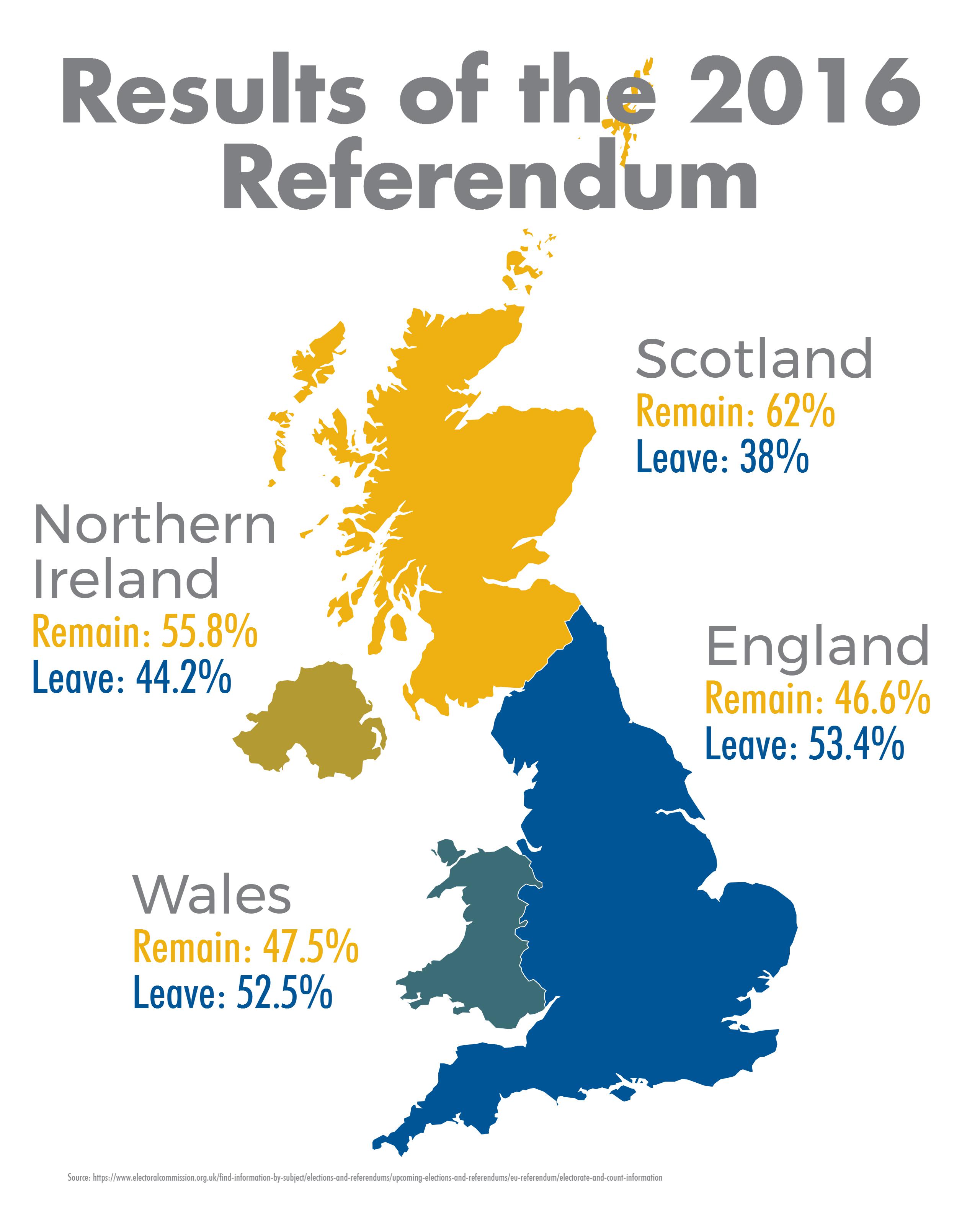

The EU referendum has been divisive in the country. Although it is now commonly accepted that Britain will eventually leave the EU in some form, the nature of that departure is undetermined. Places like London, Scotland, and Northern Ireland voted overwhelmingly to remain in the EU, and seek the softest Brexit possible—one that will maintain the benefits of the single market and the freedom of travel. The fallout from the vote has prompted Scotland to call for a second independence referendum, which would permit it to stay within the EU. If successful, it would lead to the breakup of the United Kingdom. In Northern Ireland, the shared border with Ireland means the UK’s departure from the EU poses problems for free movement, the single market, and the maintenance of the peace agreement between the two countries. A strong Conservative government pushing for a hard Brexit will likely lead to both Scotland and Northern Ireland calling for their own relationships with the EU.

As the UK grapples with a shifting domestic political ecosystem, and navigates the Brexit negotiations, it is looking to its allies for reassurance and support, particularly in terms of the economy and trade relations. It will also look to maintain a prominent position within the international arena as part of other international institutions and alliances. Therefore, the United States has an important role to play in offering support and stability in Britain’s transatlantic relations, and encouraging it to continue to play an active role.

The continuation of the US-UK relationship should be defined by a policy of “constructive commitment,” providing a steady, dependable partnership and supporting Britain as it navigates the new terms of its European relationships. “Constructive commitment” involves six steps:

- Encourage a constructive Brexit. Brexit is the biggest issue facing the UK at present, and it is in the United States’ interest for the UK to avoid an acrimonious divorce from the EU. It should encourage the UK and EU to soften the potential economic and political implications of Brexit, and to maintain good relations with one another throughout the process. In European defense and security cooperation, in particular, the United States should emphasise the importance of the UK remaining a credible and significant player in the region.

- Reinforce the importance of trust at the heart of the relationship. Recent breaches in intelligence sharing have undermined trust in UK-US relations. Renewed commitments to secrecy in intelligence sharing, and the transfer of information relating to security threats, will be important for maintaining current levels of exchange and cooperation in diplomatic interactions. This is particularly important given recent terrorist attacks in the UK. Criticism of London Mayor Sadiq Khan following the recent attacks further contributes to a negative image of American leadership and is both unpopular and unwelcome, particularly in the capital.

- Commitment to climate change and the environment initiatives. The US decision to withdraw from the Paris Agreement has provoked serious concerns in the UK and beyond. The agreement promises cooperative efforts to combat climate change as a pressing and shared international challenge. The US decision to leave, and to seek to renegotiate the terms, undermines confidence in the United States and weakens its international standing.

- Engage with the UK on trade as it looks set to move out of the single market. Britain will be seeking more bilateral partnerships on trade and industry with the United States, and will hope it is not put at the back of the queue in negotiations. Given US concerns about its industries and jobs in the UK, there are mutual advantages to cooperation.

- Continued commitment to transatlantic allies in NATO. The extent of US commitment to NATO is unclear, and there is growing mistrust between NATO allies and the United States. Reassurance through actions, and an effort to invest in transatlantic relations, will be needed to allay concerns of NATO partners, particularly on the eastern border.

- Provide assurances that British citizens will be able to travel with ease to the United States. Interrogations on entry to the United States, requests to hand over social-media passwords, and a ban on laptops will deter people from travelling to the United States.

Britain is facing a sustained period of uncertainty in its domestic politics, both as a result of Brexit and of wider societal and political changes. Over the coming years, the UK will look to the US to provide the stability, reliability, and friendship that have traditionally marked US-UK relations in order to ensure that together they can navigate increasingly complex global challenges.

Source: https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/find-information-by-subject/elections-and-referendums/upcoming-elections-and-referendums/eu-referendum/electorate-and-count-information

Source: https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/find-information-by-subject/elections-and-referendums/upcoming-elections-and-referendums/eu-referendum/electorate-and-count-informationClaire Yorke is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council. Based in London, UK, she is currently a doctoral student in the Department of War Studies, King’s College London, where her work examines the role of empathy in diplomacy. Prior to this, Claire worked for four years as the manager of the International Security Research Department at Chatham House, where she covered a broad spectrum of topics relating to international security and defense. She began her career as a parliamentary researcher in the House of Commons, where she focused mainly on defense policy.