A series of unrelated events happened in Israel. Fingers are pointing at Hezbollah.

Tensions have been unusually high along the Lebanese-Israeli border. But war, or a large-scale conflagration, is not imminent. Its usual bellicose rhetoric aside, Hezbollah remains too constrained by domestic Lebanese factors—namely the country’s ongoing economic deterioration—to engage the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) in battle. Instead, for the foreseeable future, Hezbollah can be expected to continue harassing the Israelis through various means and proxy actors that would provide it with plausible deniability.

In early March, Lebanese soldiers and border residents clashed with IDF troops conducting engineering work near the Blue Line: the de facto boundary drawn by the United Nations (in the absence of a mutually agreed-upon international border) between Lebanon and Israel after the IDF’s withdrawal from south Lebanon in 2000. Hezbollah’s Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah heaped praise upon residents and attributed the IDF’s restraint during the incident to the supposed “deterrence” the group had created against Israel, rather than the Israeli army’s strict rules of engagement.

“We had been used to [Israelis] killing, wounding, kidnapping, detaining, and bombing [us]…without fear of a deterrent,” he said. “But today, at the distance of a meter or less…[Lebanese] civilians and Lebanese army soldiers scream in their face and draw weapons against them, and the [Israelis] are forced to retreat.” The difference, Nasrallah claimed, was “the enemy’s knowledge of the presence of the resistance, and its high level of readiness.”

Two weeks later, on March 21, two IDF soldiers were wounded on the Israel-Lebanon border due to the explosion of an old landmine. Hezbollah’s media was the first to report on the event, and Resistance Axis propaganda affiliates subsequently released a schadenfreude-laden video mocking an IDF soldier who lost his leg in the incident. However, Hezbollah does not appear to have been responsible, and the presence of their reporters in the area seems to have been a matter of coincidence. According to the IDF, the landmine may have slid from its original location due to heavy rains and exploded during routine engineering activity on the northern side of the security barrier, which is still within Israeli territory.

However, the most serious incident occurred in mid-March, when an individual—who, in all likelihood, infiltrated Israel from Lebanon—planted an improvised explosive device (IED) at a traffic junction in the northern Israeli city of Megiddo. The explosive, which bore hallmarks of Hezbollah construction, wounded an Israeli citizen in the area. The suspected terrorist was killed two days later by Israeli security forces while wearing an explosives belt.

These incidents—in addition to the months-long harassment of northern Israeli residents by Hezbollah operatives using laser pointers, as well as the group’s redeployment along the border—do not portend an imminent escalation between Israel and the Lebanese militant group, or even a lower degree of direct friction between the two adversaries.

The mine incident can be discounted immediately as a factor hinting at imminent escalation. The IDF has stated conclusively that Hezbollah was not involved at all and that the event resulted from unfortunate natural causes, with proximity to the other two events being pure coincidence.

While Hezbollah attempted to take credit for the border friction between Israeli soldiers and Lebanese residents, this also did not occur at the group’s behest. Nasrallah’s comment on the matter must be understood as part of the group’s overall propaganda narrative aimed at a domestic Lebanese audience, constantly stressing Hezbollah’s alleged role in deterring the rapacious “Zionist enemy.” In short, it is part of Hezbollah’s attempt to exploit events outside of its control to prove its continued relevance to the Lebanese people, especially its support base.

The IED incident in Megiddo stands out as different from the other two events and hints at Hezbollah’s involvement—albeit indirectly. According to the IDF, the attacker infiltrated Israel from Lebanon, crossing the border above ground with a ladder at a specific point of vulnerability. An IDF official noted that this would have required the infiltrator to have considerable intelligence gathering at his disposal. Once inside Israel, the attacker secured an electric scooter to travel around the north of the country, suggesting to security forces that he may have had help inside Israel. Furthermore, according to the Israeli army, the construction of the explosive device in his possession was dissimilar to those used by Palestinian militant groups, with its sophistication suggesting that the device was built or supplied by Hezbollah, Iran, or Russia.

Nasrallah commented on the incident on March 23, but did not claim it for his group. While he suggested that his silence on the matter stemmed from a desire to increase the alleged “confusion” gripping Israel as part of Hezbollah’s “psychological warfare”, it may also be that the group was not directly responsible.

In fact, there are indications that the infiltrator was not a member of Hezbollah. The main indicator is that he was wearing an explosive belt to carry out a suicide bombing. Hezbollah has not conducted such an attack since December 30, 1999. In all its engagements since then, including attacks against Israel, its actions during the Syrian civil war, or its involvement in Iraq or Yemen, the group has refrained from conducting such attacks.

Furthermore, Israeli reports indicate that, in recent weeks, Hezbollah has permitted the deployment of four hundred Palestinians affiliated with Hamas from refugee camps in Sidon and Tyre, along the Israel-Lebanon border. These individuals are Sunni and remain full-fledged members of Hamas, a group that continues to count suicide bombings as a legitimate tactic. It is entirely plausible that one of these operatives engaged in disruptive activities along the border crossing into Israel with Hezbollah’s tacit approval or perhaps active assistance.

Moreover, the Galilee Forces-Lone Wolves—a little-known Lebanon-based group that splintered from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and commanded by an individual named Fadi A-Mallah—claimed the Megiddo attack. The group was formed at the outset of the Syrian civil war and is made up of local Palestinians that are trained and equipped by Hezbollah and Iran to fight alongside Bashar al-Assad’s regime. The IDF has targeted the Galilee Forces in Syria in the past after discovering the group’s network of contacts among Arab Israelis and Palestinians within Israel and the West Bank, and its intention to leverage that network to carry out attacks within Israel.

The group’s continued affiliation with Hezbollah is implied by the fact that the two organizations even share propaganda methods, including near-identical videos under their respective branding.

Facilitating an attack by this group or other Palestinian factions would allow Hezbollah to cause insecurity behind Israeli lines while maintaining plausible deniability, thus, avoiding Israeli retaliation or an undesired escalation. Despite Nasrallah’s bluster and recent fixation on the ongoing discord within Israel over the Netanyahu government’s judicial reforms, Hezbollah is still in no position to enter a security conflagration with Israel. Directly carrying out and claiming a terror attack within Israel would certainly carry the risk of such an escalation—or even war. In the background of Nasrallah’s commentary on the IED incident, Lebanon’s currency was continuing its collapse, losing almost 98 percent of its value on the black market while Lebanon depleted two-thirds of its $30 billion reserves.

War or an escalation with Israel in such a situation is simply untenable for Lebanon and, by extension, Hezbollah, which needs the country to maintain some level of stability to continue its steady growth. Nasrallah is acutely aware of his country’s dire straits, and foreign powers, including Saudi Arabia, are unlikely to reinvest in Lebanese construction after a new round of violence with Israel.

Nasrallah’s fiery threats against Israel in his latest speech must be understood within this context. The group is incapable of claiming or admitting it facilitated the Megiddo attack. But it is equally incapable of admitting weakness or limitations in the face of Israel without raising questions about its continued utility. A resistance movement unable to deter its primary enemy is of questionable value, after all, and the group could not remain silent after threats made by then-Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Galant. Hezbollah must always create the impression that it has the upper hand against Israel and have the final word. But this is little more than propaganda for domestic consumption.

However, Hezbollah isn’t entirely inactive. As its possible assistance to the Galilee Forces suggests, behind the scenes, the group is continuing its years-long effort to fuel violence against Israel in the West Bank while attempting to spread that conflagration into Israel itself. Doing so provides Hezbollah with an option to strike behind enemy lines and allows them to maintain pressure against Israel while being removed enough from the violence to avoid suffering the consequences of its actions.

David Daoud is a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council.

Further reading

Wed, Sep 1, 2021

An escalating Israel-Iran conflict could sink the JCPOA

IranSource By

Rising tensions between Israel and Iran have reached an alarming stage in recent weeks. What used to be a shadow war of covert operations, sabotage, and proxy conflict is turning into a more direct military confrontation between the long-time regional adversaries.

Thu, Jan 19, 2023

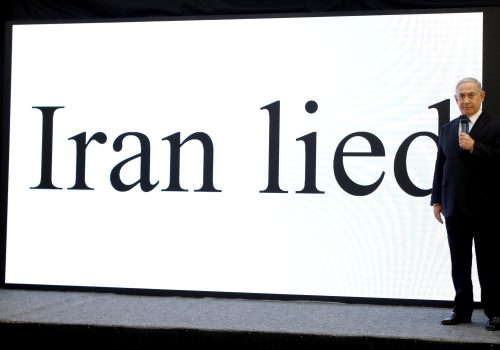

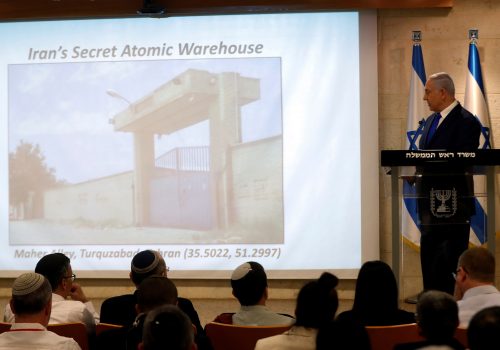

Netanyahu’s Iran policy is expected to fail—again

IranSource By Danny Citrinowicz

The biggest problem that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has today is the fact that he will have a tough time rallying the Joe Biden administration.

Thu, Mar 30, 2023

Israel and the international community have deep gaps on the Iran nuclear issue. It’s time the Israeli government adopts fresh thinking.

IranSource By Danny Citrinowicz

The Israeli government must understand that there is a need to dissociate between the nuclear issue, which has only a diplomatic solution, and Iranian malign activities.

Image: A UN peacekeepers (UNIFIL) vehicle drives near a picture showing Lebanon's Hezbollah leader Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah in Adaisseh village, near the Lebanese-Israeli border, southern Lebanon, October 11, 2022. REUTERS/Aziz Taher