Israel and the international community have deep gaps on the Iran nuclear issue. It’s time the Israeli government adopts fresh thinking.

The international community’s Iran policy was never close to that of the Israeli government. However, in recent years—especially after the Donald Trump administration’s withdrawal from the multilateral agreement known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2018—Israel’s constant concerns regarding the Islamic Republic are becoming realized.

Against the backdrop of difficulties in returning to the JCPOA, Tehran is speeding up uranium enrichment. Using advanced centrifuges, Iran is currently enriching at a high level (60 percent) that is difficult to justify on a civilian scale. Moreover, finding uranium particles at near weapons grade (84 percent) substantiates the permanent Israeli claim that Iran seeks to produce a nuclear weapon. At the same time, Iran seems to be making all possible mistakes in its foreign policy.

For starters, Iran’s support for Russia in the Ukraine war, which is reflected in the sending of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and the ridiculous attempt by the clerical establishment to deny this. This is alongside the regime’s violent repression of protesters since mid-September 2022, as well as foiled Iranian intelligence plans to harm Iranian opposition figures in Europe. All this has led to a number of European countries pushing to designate the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) as a terrorist organization, thereby reinforcing the Israeli perception that the Islamic Republic is, in the words of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, a “dark regime” that seeks to create terrorism around the world.

Moreover, alongside in-depth discussions between Israel and the United States on the Iran file in recent months—including a meeting at the White House—military coordination on this issue is also deepening. Just a few weeks ago, the “largest-ever bilateral military exercise” by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) and the US Central Command (CENTCOM) took place, which, according to some outlets, reportedly simulated an “attack on Iran.”

Concurrently, Iran continues to transfer weapons to its proxies in the Middle East, while attacks continue to be carried out by Iran-supported elements on Western and especially American interests in the region—all of which strengthen the Israeli claim about Iranian expansion in the region.

Despite these significant developments, and even though Israeli views regarding Iran are finally gaining international approval, there is still a deep and unbridgeable gap between Israel and the international community regarding the Iran nuclear issue.

The first development concerns the American intelligence community’s annual intelligence assessment presented to the US Congress. It contends that, contrary to Israel’s claims, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei had not decided to produce nuclear weapons after Iran abandoned a previous attempt to obtain one in 2003 (when it had an active military nuclear program).

In addition, per the intelligence assessment, Iran has been “pushed” into unprecedented actions in its enrichment program due to actions carried out by “unknown elements” against its nuclear program, such as the assassination of the country’s lead nuclear scientist, Mohsen Fakhrizadeh. Moreover, the report even hinted that the correct way to prevent Iran from enriching uranium to military-grade (90 percent) is by returning to the nuclear agreement.

In other words, according to the American intelligence community, the moves made by Iran are not to produce a bomb, but to force a return to the agreement, which may be the only option to stop the advancement of its nuclear program.

The second development concerns the meeting of the Board of Governors of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). It was expected that the board would not only condemn Iran but perhaps take more serious measures against it, such as transferring the Iranian file to the United Nations Security Council due to its nuclear advancement, which Israel wanted.

But here, too, the gap between Israeli expectations and the activity of the IAEA is still very wide. Just before the Board of Governors was convened on March 4, IAEA Director General Rafael Grossi traveled to Iran. There, he met with Iranian leadership and managed to extract not only a roadmap for resolving the “open files,” an issue that has become a stumbling block in the relationship between Iran and the IAEA—which makes it difficult to return to the nuclear agreement—but also for Iran’s willingness to allow tighter supervision, especially of the enrichment facility at Fordow. The conduct of the IAEA and senior Iranian officials indicate that, in the face of pressure, the parties sought to find a path forward that would leave the option of a return to the nuclear agreement, despite all the setbacks.

Interestingly, the agreements between Iran and the IAEA were only the preview of the latest development: the Chinese-brokered agreement to renew diplomatic relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia. Israel, who was eager to join forces with Saudi Arabia and form a regional alliance against Iran, discovered that the regional spearhead of this theoretical alliance had decided to get politically closer to Iran. This rapprochement is also in line with the steps led by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) over the past year to strengthen its diplomatic and, in particular, economic ties with Tehran, with the understanding that the best way to prevent escalation in the Gulf region is through integration with Iran.

These events highlight the gap between Israeli policy and the international community, including the United States and Gulf states. Chief among them is the understanding that a return to a nuclear agreement is the leading and perhaps only option to put Iran’s nuclear genie back in the bottle and roll back its enrichment progress since any other move is liable to push its nuclear program to weapons grade.

This fact requires Israel to think freshly about the Iranian nuclear issue. The Israeli government must understand that there is a need to dissociate between the nuclear issue, which has only a diplomatic solution, and Iranian malign activities like their support for proxies.

As long as the world is concerned that its actions may push Iran forward in its nuclear program—given the fact that Tehran has no other significant tool in its nuclear toolbox to retaliate against any actions against them—countries will probably refrain from taking harsh actions against Tehran concerning other negative aspects of its policy. Moreover, as long as the West assumes that Iran is not taking any actions that would lead to building a nuclear weapon, no country—including the United States—will decide to use force against the Islamic Republic or its nuclear program, and, therefore, Israel may again be left alone.

The bottom line is that the recent developments indicate that the world understands the need to use carrots in addition to sticks against Iran. Posing a military threat to Iran may be important in several ways, but without giving Iran incentives, it will be very difficult to persuade Iran not to enrich at 90 percent, or weapons-grade, which improves its ability to acquire a nuclear weapon in the future if it so desires.

In general, it is important to remember that Iran built its nuclear program to ensure the regime’s future—that is, the program is a means and not an end. If it is possible to assure Iran of the future of the regime in other ways—including a willingness to ease economic and diplomatic relations—it is very doubtful that Iran will choose the path of a nuclear bomb.

In stark contrast to its current strategy, Israel must reconsider the validity of the nuclear agreement as a tool in its foreign policy regarding Iran. A return to the JCPOA (or something akin to it) has a price: the lifting of sanctions. However, even this price will not lead the world to cooperate with the regime, as it conducts many other negative activities that push potential partners away, such as selling weapons to Russia, sending squads to harm various elements in Europe, and brutally suppressing protesters.

If Israel adheres to its current strategy and seeks to use kinetic pressure against Iran to topple its nuclear advancement, it should expect—despite all the developments of recent months—to be left alone in the face of Iran’s accelerated nuclear program, even if Iran enriches at 90 percent. Perhaps it is time Israel follows the approach of the Gulf states and adopts a more complex policy that will integrate diplomatic actions rather than just military ones.

Danny Citrinowicz is a nonresident fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs. He served for twenty-five years in a variety of command positions units in Israel Defense Intelligence (IDI). Follow him on Twitter: @citrinowicz.

Further reading

Tue, Dec 8, 2020

A history of continuity in Iran’s long nuclear program

IranSource By Sina Azodi

Iran’s interest in developing a nuclear deterrent is often attributed to the Islamic Republic. However, in reality, this interest predates the 1979 revolution and reflects a deep-seated desire for national prestige and development, as well as a need to deter regional rivals.

Thu, Sep 8, 2022

A revived nuclear deal doesn’t stop Iran’s backing of Houthis in Yemen. More must be done.

IranSource By

The international community seems indifferent to the risks of Iranian hostile behavior and intrusion through its support of Yemen’s Houthi rebels.

Thu, Jan 19, 2023

Netanyahu’s Iran policy is expected to fail—again

IranSource By Danny Citrinowicz

The biggest problem that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has today is the fact that he will have a tough time rallying the Joe Biden administration.

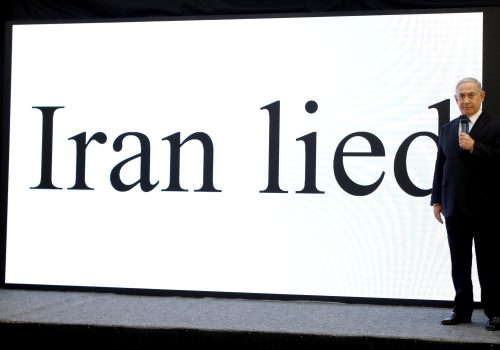

Image: Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu speaks at a news conference in Jerusalem September 9, 2019. REUTERS/Ronen Zvulun