An American martyred himself for the people of Iran. Here’s his story.

The story of Howard Baskerville is one I have known nearly all my life.

Baskerville was a twenty-two-year-old Christian missionary from Nebraska who traveled to Persia (modern-day Iran) in 1907 for a two-year stint teaching English and history and preaching the gospel. He arrived in the northwestern city of Tabriz smack dab in the middle of what history would come to know as the Persian Constitutional Revolution.

Spurred by the suffering of the Iranians around him, Baskerville gave up his missionary post, surrendered his American citizenship, and joined the revolution.

On April 20, 1909, he led a force comprised of his own students on an ill-fated mission to break through Mohammed Ali Shah’s siege and get food to the starving inhabitants of Tabriz. He was shot and killed in the attempt.

The Persian Constitutional Revolution may not have transformed the country into a lasting democracy. But it set the precedent for the exercise of people power in Iran, creating one of the most robust protest cultures in the world. Indeed, the legacy of that revolution can be seen today in the tide of social unrest that has washed over the country since mid-September.

However, the memory of Howard Baskerville and his sacrifice has been all but lost in both Iran and America. I wrote An American Martyr in Persia—the first biography ever written about the young man—because I believe every American and every Iranian should know his name, and that name should be a reminder of all the two peoples hold in common. My hope is that his heroic life and death can serve in both countries as the model for a future relationship—one based not on mutual animosity but on mutual respect.*

What follows is an excerpt from An American Martyr in Persia: The Epic Life and Tragic Death of Howard Baskerville by Reza Aslan:

With the arrival of winter, the bare yellow hills surrounding Tabriz appear white and shimmery. The salt-and-sulfur valley floor is buried in snow. Snow blankets the homes, the mosques, the schools. It leaves smooth white mounds over the piles of garbage, the discarded bricks, and the broken pieces of concrete that somehow always seem to accumulate in the streets. In this city, no mess is ever cleaned up unless some rich nobleman complains about it.

Tabriz is not a place of great architectural wonders, but the natural scenery surrounding the city can take the breath away. Stand atop any of the flat-roofed homes and you can see for miles around. There, in the south, is the broad dome of Mount Sahand. In the north, the high ridges and defiant valleys of the Qaradagh. And, in between, a sweeping view of the flat valley, bursting here and there with groves and orchards that appear from this distance like a mirage. In a couple of months, when the snow finally melts, the valley will be overrun with daffodils.

For Howard Baskerville, the fall semester had been filled with glee and wonder. He’d been told Persia was a land of treachery and falsehood, its people deceitful and degraded, its achievements negligible and ruined. It had only been a few months but, so far, his experience in Tabriz had put the lie to those dispiriting missionary reports. He loved his students, and they loved him. He had made one or two dear friends among the faculty. He was taking courses in French and Turkish and was slowly picking up Persian. He read entire volumes of books on topics as eclectic as systematic theology and the lives of English poets. He stayed up at all hours, drinking tea in cafés and talking politics with the locals. He gorged himself on Persian cuisine. He boxed and played tennis and occasionally rode horses. All in all, Persia was shaping up as precisely the grand adventure he had dreamed of when he filled out his missionary application.

With winter now upon them, the excitement of those early months in Tabriz was, like the January chill creeping into the valley, beginning to settle into a recognizable routine. The first two classes Baskerville was assigned to teach at the American Memorial School were English and history, and he poured all his energy into being the best instructor he could be. He was sober and serious, yet always patient and kind, even when his students stumped him with some vaguely worded question posed in unintelligible English.

This was Baskerville’s first teaching experience, but he’d had one or two formidable teachers of his own back at Princeton, and he strove to apply the lessons he had learned from them in his own classroom. In fact, he created his own version of Princeton’s preceptorial system in Tabriz, supplementing his class instructions with personal, one-on-one mentorships with a handful of students, with whom he formed a tight bond. He tried not only to teach his students but also to encourage and inspire them, to foster within them a love of learning. Sadeq Rezazadeh Shafaq, who enrolled in both of Baskerville’s classes, called him one of the best teachers he’d ever had. “He always gave us hope that gradually we were going to understand more and more,” Sadeq recalled, “and, in fact, his pleasant demeanor and attractive personality awoke in us a real desire to learn more and work harder.”

The missionary teachers at the school were a close-knit bunch. Along with Samuel Wilson, Frederick Jessup, Charles Pittman, and John Wright, Howard Baskerville was one of only five American men teaching at the school—all of them proud Princetonians. Even William Doty, the new American consul general in Tabriz, was a Princeton man. He and Jessup were old friends; they’d both graduated from Lawrenceville Preparatory in New Jersey, an elite boarding school that was, at the time, almost wholly composed of missionary children sent home by their parents to receive a high school education before inevitably matriculating at Princeton.

Doty, of course, was not a missionary but a diplomat, though, in his mind, there wasn’t much of a difference between the two roles. He was a devout Presbyterian with a seminary degree who seemed genuinely to believe that his duty as consul general was to promote the work of the West Persia Mission, rather than, say, issue visas or fill out birth certificates. On more than one occasion he was reprimanded by the State Department for trying to “extend his consular jurisdiction over the morals of naturalized American citizens residing in his district.” That is to say, evangelizing.

William Doty was the first to serve as the US consul general in Tabriz. Despite the city’s strategic importance, it had never before had an American consulate. When he arrived in January of 1907—sun-kissed and bronze from his previous post in Tahiti—he was escorted directly to the Citadel. The ancient, crumbling structure, which sat in the center of the city like an anchor in the desert, would be the new American consulate office. With its high, thick walls and towering summit, this was not only the most secure location in Tabriz; it was, by far, the tallest. Now, no matter where in the city you were, you could always see the Stars and Stripes, waving in the wind.

Doty had been in Tabriz less than a year when Baskerville arrived, but he was already a fixture at the Wilson home. He spent most of his nights there, dining with the family, singing at the piano, telling tall tales by the fire. Baskerville would have had no choice but to sit with him at the Wilson table, patiently listening to his adventures among “the savages” of Tahiti. But there was little chance the two men would become friends. They had vastly different views on what was taking place in Persia. Doty fully endorsed the American government’s position that the Persian Constitutional Revolution had no hope of succeeding; such a quixotic venture could not be supported by the United States. The State Department had said as much in a memo it recently sent to Persia: “This government can take no cognizance of any subversive movement unless it should succeed to actual power.”

Doty was also, by all accounts, a bit of a boob. He was earnest and gregarious, but also wide-eyed and overly dramatic, eager to insert himself in everyone’s affairs. He approached Persia with undisguised exuberance—an easy mark for the city’s merchants and hustlers. His comedic attempts to exert his authority over the native population were a constant source of ridicule in Tabriz. The children especially had great fun over Doty’s mangling of the local tongues. “Mr. Doty’s nervousness and his tendency to exaggeration are so great that he has become a kind of joke to other foreign residents,” reported the American legate in Tehran, John B. Jackson.

Baskerville had a better chance of forming a friendship with Frederick Jessup. The two shared similar interests, including a passion for tennis (Jessup was a two-time men’s singles champion back in New Jersey). Like Baskerville, Jessup came from a family of preachers, although his were titans in the Presbyterian Church. Frederick’s father, Henry Harris Jessup, spent fifty-three years spreading the Gospel in Syria and was a world-renowned theologian. He was equally renowned for his contemptuous views about the people he served: in “the conflict between civilization and barbarism, Islam must be the loser,” he famously wrote in his masterwork, The Mohammadan Missionary Problem.

Frederick Jessup had a deep and abiding commitment to the people of Tabriz he served and was among the more vocal pro-constitutional missionaries at the American Memorial School. But he, too, dismissed Persia as “a fanatical Moslem [sic] land,” tarred the religion of Islam as “the strongest and bitterest enemy of Christianity in the world,” and considered nearly the entire population of the country to be “under bondage to every form of sin.”

Besides, Jessup may have been the American closest in age to Baskerville at the school; but he was still ten years older. And he was married. In fact, every male missionary at the school was married, and they all had children. Baskerville was the sole single American man in the entire school. So it’s no surprise that he would spend most of his free time with members of the mission community who were closer to his age, especially the fifteen-year-old diarist, Sarah Wright, and the eldest Wilson girl, Agnes, often taking them out on shopping excursions or for horse-riding lessons in the countryside. Sarah’s diary contains many entries in which Baskerville would show up at her house unannounced, horse reins in hand, wanting to know if she’d like to “take a ride.” She would grab her mother’s fur coat, and off they’d go.

It’s difficult to know exactly when his friendship with Agnes began raising eyebrows. Agnes had matured into a wise and worldly woman: a politically conscious, socially active sixteen-year-old with a strident feminist streak and passionate opinions about the country of her birth. “All that is needed to redeem Persia is to teach the nation how to help itself along the lines of modern civilization,” Agnes once told an American reporter. “Foreign nations must not be content to take all they can get from Persia and give nothing in return.”

Howard and Agnes spent a lot of time together. They lived under the same roof. They shared most meals. They sat with each other at church. They stayed up late singing songs and telling stories. They exchanged books and secrets. It was only a matter of time before Samuel Wilson started to notice the romance budding between them. This may be why, at some point early in the new year, Howard Baskerville was asked to find other lodgings in town. He moved out of the Wilson home and into a cramped room on campus reserved for visiting faculty.

***

The move may have pulled Baskerville away from Agnes, but it also pushed him toward Hassan Sharifzadeh and his fellow revolutionaries, with whom he could now spend even more of his free time. Under Hassan’s protection, Baskerville was given entry into Tabriz’s so-called secret societies. These were unofficial councils formed by young Social Democrats who were more strident in their views of the revolution and more uncompromising in their tactics. They gathered clandestinely at night to discuss ways to fight corruption and tyranny and to awaken the people to the cause of liberty. Members read speeches, created pamphlets, formulated demands, debated the articles of the new constitution, and strategized ways to defend the democratic rights they had already won.

Can you see Baskerville in one of these dark, smoke-filled rooms, listening to those fresh-faced revolutionaries arguing about popular sovereignty and inalienable rights, his mind harkening back to another band of revolutionaries who also had no chance of succeeding yet, nevertheless, did?

The secret societies tended to attract members who were more radical, more progressive, and more secular-minded than most other constitutionalists in Tabriz. Some members served in the anjoman; a handful had been elected to parliament. In both organizations, they were already the loudest, most unyielding voices urging forceful opposition to the crown. But the shah’s failed attempt to shut down parliament the previous December had pushed many of them past the point of compromise. As far as they were concerned, the curtain had been pulled back; everyone could now see Mohammed Ali for what he was. What more doubt could there be as to his true intentions or his true character? Had he not stood before the nation, placed his hand upon the Holy Quran, and sworn to uphold the constitution during his coronation? What kind of ruler would so brazenly break a solemn vow made before God and men?

An “oath-breaker,” that’s who. That is what the shah was called in the secret society meetings Baskerville attended. What did it matter that the shah was forced to retreat? What difference did it make that he had apologized for his actions against parliament and once again pledged to uphold the constitution? His word was forfeit, and so, therefore, was his reign.

The secret society members held enormous sway over the anjoman in Tabriz, and it was under their pressure and influence that the council began sending telegrams to other anjomans across Persia demanding the shah’s immediate abdication. “The Shah swore an oath to accept the constitutional law and has now broken his oath,” the telegrams read. “For this crime, the people of Azerbaijan remove him from power. . . . You, too, remove him and inform the embassy.”

This was a jaw-dropping declaration. Never before in Persian history had the people claimed the right to legally remove the shah. The notion that God had placed the shah on the throne and thus only God could remove him from power had been baked into the Persian psyche for thousands of years. It was a belief that could be traced back to the first “King of Kings,” Cyrus the Great.

But the constitution had fundamentally challenged that view, not by denying the divine authority of the throne, but by reimagining that authority as a trust given by God to the people, and then by the people to the shah. Article 35 of the Supplementary Fundamental Laws stated in no uncertain terms that “the sovereignty is a trust confided (as a Divine gift) by the people to the person of the King.”

If the people could, on behalf of God, gift the throne to the shah, then the people could, on behalf of God, take the gift away.

“Has His Majesty forgotten that . . . he does not have a deed to absolute rule from the skies and the God of the Universe?” read a collective statement from the country’s leading anjomans. “No doubt that if he pondered for a moment he would realize that his monarchy is dependent upon the acceptance or rejection of the nation. He would realize that the same people who have raised him to this high level and recognized him as shah are quite capable of removing him and choosing another to replace him.”

In the end, all these telegrams and declarations amounted to nothing. Mohammed Ali had publicly apologized for trying to shut parliament down and vowed not to do so again (a lie, as he was, at that moment, scheming with Shapshal and Liakhov to do just that). An agreement was reached whereby the shah swore to abandon his opposition to the constitution once and for all, and parliament promised to put an end to “outrageous acts” such as the brazen calls for his abdication. The agreement calmed the waters somewhat in Tehran.

But Tabriz would not move on. The shah’s attack on parliament had radicalized the city. If anything, the calls for his abdication were growing louder, and not just among the secret societies. What had seemed like an impossible idea just a few months ago—the removal of the shah by the will of the people—was becoming an increasingly accepted possibility on the streets of Tabriz. Mohammed Ali’s reign was polarizing the city. It was splitting the most ethnically and religiously diverse province in all of Persia into two opposing camps: the royalists, who supported the shah; and the nationalists, who supported parliament and the constitution.

Ironically, the growing polarization in Tabriz only strengthened the shah’s hand. What Mohammed Ali understood about the city of his birth is that its traditional divides could be manipulated to his advantage, given enough money and resources. His cause was bolstered by some of the more extreme actions taken by the anjoman in Tabriz. Its attacks against the city’s large landowners and wealthy merchants (not to mention its forceful expulsion of anti-constitutional clerics) had created potent enemies among the city’s rich and powerful. The more the new political order came into focus, the more those with vested interests in the status quo began to turn against it.

Long before his bungled attempt to shut down parliament, Mohammed Ali Shah had been sending carriages filled with money and weapons to his allies in Tabriz. He had purchased the services of hundreds of lootis from all over the province of Azerbaijan and shipped them off to secure his interests in the city. He had even urged his backers in Tabriz to launch their own rival anjoman—which they did in the summer of 1907, giving it the strategic name of Eslamiyeh (“the Islamic Anjoman”), a blatant attempt to pull the city’s pious poor away from the constitutional cause.

With the city now bitterly divided and teetering on the edge of civil war, the American Memorial School became neutral ground. Samuel Wilson was diligent in trying to keep the chaos engulfing the city from penetrating the tranquility of the school. No doubt he was worried about the country’s future. But he had spent years building a reputation in Tabriz as a trusted figure, a man beholden to no one, in favor of no faction. He could not be seen as taking sides in Persia’s political affairs, regardless of what was at stake.

Early in the revolution, the Wilsons had made a conscious decision to maintain the school schedule no matter what else was happening outside of campus. Yet there was only so much they could do to tamp down the rising revolutionary fervor among the student body. It certainly didn’t help matters that two of the city’s most prominent revolutionaries happened to be members of the faculty. Mirza Ansari, the school’s youthful international law teacher, was spending the bulk of his time giving rousing speeches in front of the Telegraph House, extolling the virtues of the constitutional cause, while Baskerville’s friend, Hassan Sharifzadeh, was conducting daily campus meetings of the Union of Students, discussing ways to bolster the defense of the constitution among the people.

In Baskerville’s English and history classes, the conflict with the shah dominated discussions. How could it not? The students may have been shielded somewhat from the events roiling the city, but their friends and families were mired in it. Tabriz had the feel of a small, provincial town. Everyone knew everyone else; many of the residents were related to each other in one way or another. The fighting on the streets was as much a family feud as it was a civil conflict. So then, how was Baskerville expected to keep the conflict from intruding into his classroom?

It would have been natural for his students to assume their young American teacher was an ally to the cause, and there was no reason to think Baskerville wasn’t. He may very well have been deeply invested in the success of the Constitutional Revolution. After all, his closest friend was one of its most vocal proponents. And it could not have been lost on him that the principles he had just studied at Princeton—principles he had abandoned his family legacy to pursue; principles he would ultimately give his life to defend—were being battled over just outside his classroom window.

But he had been in the country barely four months, and in that time, he had been repeatedly instructed by both Samuel Wilson and William Doty not to engage in any activity outside of his responsibilities as a missionary and teacher, in accordance with the US government’s explicit mandate of neutrality for the West Persia Mission.

This must have come as something of a shock to the people of Tabriz. The long presence in the city of American missionaries like the Perkinses and the Wilsons had given the population an impression of America as a benevolent power. What little most Persians knew about American history had primarily to do with its own fight for independence against a corrupt and out-of-touch monarch. Wasn’t this fact reason enough for America to find common cause with the Persian Constitutional Revolution?

The US government, however, wanted nothing to do with Persia or its struggle for independence. Not only did the United States have no interest in antagonizing the British and Russians; it had no faith in Persia’s revolutionaries. Doty’s superiors in Washington had concluded that Persians were too ignorant of constitutional government, too uneducated and uninformed, too backward to be able to create anything approaching a real democracy. “History does not record a single instance of a successful constitutional government in a country where the Mussulman religion is the state religion,” read an internal State Department memo. “Islam seems to imply autocracy.”

There’s no way Baskerville would have agreed with that statement. He had been taught by Woodrow Wilson to believe that the rights of the individual were absolute and nonnegotiable. This was no mere political philosophy. It was a religious conviction. Democracy was a gift granted by God to all peoples everywhere. What difference did it make by what name you called that God? Democracy was either inalienable or it wasn’t. It was either universal or confined solely to Christians. The US government may have believed the latter. But not Howard Baskerville.

Still, there was simply nothing he could do about it, not without abandoning his missionary work, being stripped of his teaching position, possibly even losing his citizenship. He had no choice but to put his head down and do the job the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions had sent him here to do. He would ignore the tempest brewing in his chest whenever he watched Hassan stand before a crowd and urge them never to surrender the fight for freedom. He would bite his tongue when one of his students looked him in the eyes to ask what he could do to help the country. He would shut his ears to the occasional whiz-bang of bullets being exchanged in the streets, the dull thud of a body hitting the pavement.

He would teach his classes, read his books, ride his horse whenever he could, and try his best to pretend that none of it was happening.

Reza Aslan is a writer, professor, and an Emmy- and Peabody-nominated producer. His new book is An American Martyr in Persia: The Epic Life and Tragic Death of Howard Baskerville.

*NOTE: The introduction was adapted from An American Martyr of Persia.

Further reading

Mon, Sep 26, 2022

‘Women, life, liberty’: Iran’s future is female

IranSource By

Women, young and old, have been at the forefront of the uprising, just like every other protest in Iran over the past decades.

Fri, Sep 30, 2022

The protests in Iran have an anthem. It’s a love letter to Iran.

IranSource By

Shervin Hajipour's “For the sake of” has captivated the whole nation.

Wed, Sep 28, 2022

I’m a member of Gen Z from Tehran. World, please be the voice of the people of Iran.

IranSource By

To all the brave and beautiful people out there who know what freedom feels like, be our voice.

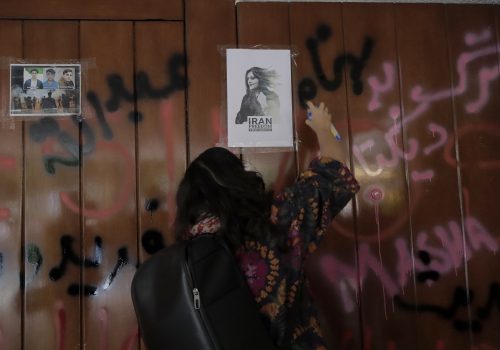

Image: Potrait of Howard Baskerville (courtesy of W. W. Norton & Company)