Analyzing terrorism sanctions on Iran and the path forward

The Donald Trump administration’s terrorism-based designation of numerous major Iranian economic entities, including the Central Bank of Iran (CBI), was a centerpiece of the administration’s “maximum pressure” strategy on Iran.

These terrorism designations might complicate the Joe Biden administration’s stated intent to rejoin the 2015 multilateral Iran nuclear agreement, as Iranian leaders are demanding the lifting of any US sanction that prevents its economic entities from operating freely in the global economy. Yet, revoking terrorism designations of Iranian economic entities might prompt some to question the Biden administration’s commitment to countering Iran’s “malign activities” in the region.

A broader debate might center on whether US policy toward Iran has been applying a relatively narrow counter-terrorism lens to a complex Iranian strategy to build influence throughout the Middle East.

The maximum pressure strategy of the Trump administration was implemented primarily through the imposition of comprehensive US secondary sanctions on every sector of the Iranian economy in a seemingly successful effort to isolate and harm Iran’s economy. The Trump administration deemed designating many Iranian economic entities as supporters of terrorism to be an effective means of deterring international transactions with those entities. The administration identified the CBI as a terrorism entity in September 2019, along with numerous other Iranian economic entities during 2018-2020, such as banks, Iran’s oil ministry and main state-owned National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC), mining companies, investment firms, the large Mobarakeh Steel Company and other manufacturers, trading companies, and firms involved in oil shipments.

Yet, this strategy represented a departure from the practices of past US administrations, which have historically applied such designations only to groups and persons cited for direct participation in terrorism or support for acts of terrorism or Iran-inspired political violence. The Trump administration justified its designation policy on the grounds that the sanctioned economic entities were generating the revenue and financial channels with which Iran supported regional factions that have committed acts of terrorism. Some experts have asserted that, because of the broad US national consensus to use all elements of national power to counter terrorism, future administrations might have difficulty revoking the terrorism designations of Iranian economic entities.

The Trump administration’s designation of numerous Iranian economic entities as terrorists raises questions for the Biden administration’s stated intent to return to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). As a condition of a mutual US and Iranian implementation of the JCPOA, Iranian leaders are demanding that the US lift all economic sanctions on Iran that were eased to first implement the accord, as well as those that were imposed subsequent to the US withdrawal from the deal in 2018.

Fulfilling these Iranian conditions might require the Biden administration to “de-list” from US sanctions not only those Iranian and Iran-related economic entities de-listed in 2016—when the JCPOA went into effect—but also economic entities sanctioned by the Trump administration – even if the economic entities have been designated as terrorist. Returning to the primary example: Iran’s Central Bank is at the hub of its financial sector and maintains accounts abroad that hold Iran’s foreign exchange assets. It can be argued that Iran will not agree to a mutual US-Iran return to full compliance with the JCPOA unless the CBI, as well as major oil export entities such as NIOC and the ministry of petroleum, are allowed to return to unfettered operations in the global economy.

The Biden administration’s potential de-listing of terrorism-designated Iranian economic entities is at the crux of the broader debate over the thesis of the JCPOA itself. The nuclear accord represented a fundamental tradeoff: exchanging the potential Iranian development of a nuclear weapon for the removal of economic constraints. US officials recognized, as expressed by then-Secretary of State John Kerry, that Iran might use an improved economic situation to support actions that are adverse to US interests, in particular the arming of regional groups that have conducted terrorism and other violence. Similarly, the Biden administration might justify de-listing all Iranian economic entities—even those with terrorism designations—on the grounds that the de-listing is a necessary sacrifice for the broader objective of ensuring that Iran does not become a nuclear weapons state.

The de-listing of Iranian economic entities that were designated as terrorist entities could spark a broader debate on the overarching US approach to Iranian support for regional armed factions. The Trump administration and many of its predecessors have tended to characterize Iran’s support for these groups as support for terrorism or as “malign activities.” However, it can be argued that Iran’s embrace of armed factions represent implementation of a strategic “playbook” to build influence throughout the region and secure its national interests.

Iran’s leadership has empowered the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Quds Force (IRGC-QF) to mold pro-Iranian armed factions into political movements that possess progressively increasing influence and capabilities. Lebanese militant group Hezbollah is an example of the degree to which Iran’s playbook has succeeded, insofar as Hezbollah has evolved from a group that committed repeated acts of terrorism into a major political actor in Lebanese governance. Similarly, with Iranian help, Hamas has evolved from a relatively small terrorist group into a political actor that exercises de-facto control of the Gaza Strip. The IRGC-QF has nurtured several Iraqi Shia militias into significant movements that hold significant numbers of seats in Iraq’s parliament. Although many of these movements continue to conduct actions that could be defined as terrorism, it can be argued that the exercise of political power and influence on national decision-making have long overtaken armed action as the primary focus of these Iran-backed factions.

Viewing Iran’s regional strategy through the lens of counter-terrorism might have hindered the development of US policies that could roll back Iranian influence in the region, such as ones that aim to resolve the regional conflicts that have provided fertile ground for Iran’s intervention.

Dr. Kenneth Katzman is an Iran expert at the Congressional Research Service. This article is written in his personal capacity and does not represent the view of CRS or the Library of Congress.

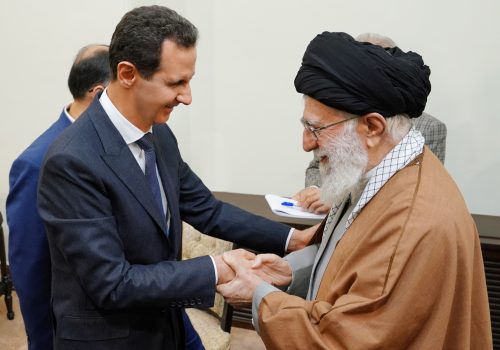

Image: Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei (R) greeting newly-appointed commander of the Quds Force of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Esmail Qaani (L), Iranian Armed Forces Chief of Staff Major General Mohammad Bagheri (C), and Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Chief Commander Hossein Salami, during a mourning ceremony in Tehran for slain top general Qasem Soleimani,Tehran, Iran on January 9, 2020. Handout Photo via SalamPix/ABACAPRESS.COM