During 2013, Iran seized on a rare opportunity to talk directly with the United States for a new round of nuclear negotiations. European countries speaking at the time to Iran to cap its nuclear program asked the US, which had been part of the nuclear talks since 2006, to join in fresh discussions with Iran. The P5+1 talks that followed between Iran and the US—along with Britain, China, France, Germany, and Russia—came with a promise that the countries would not tighten the multilateral sanctions regime against Tehran if an agreement was reached. The arrangement led to the 2015 Iran nuclear deal also known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA).Iran was enticing the US to talk once again this past month, by withdrawing some of its obligations under the nuclear deal in May. The two countries had a falling out after US President Donald Trump pulled out of the JCPOA, and re-imposed punitive sanctions on Tehran. To trigger Washington into some action to end this impasse, on May 22, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani reached out to the US by suggesting that engaging in a new round of talks was possible—if they returned to the table.

Reaching out to Washington was facilitated when tensions between Iran and some US allies in the Persian Gulf mounted in May, following attacks on four oil tankers in the Persian Gulf and a Saudi oil pipeline by Iran-backed Houthi rebels. After the attacks, Tehran accelerated plans suggesting it was open to fresh talks with the US even on its foreign policy, by proposing a non-aggression pact with US Arab allies.

Tehran’s proposal for a regional pact comes at an opportune time. Experience tells Iran that if it wants to negotiate with the US, it has to run the show with its Gulf Arab neighbors. This is not always easy to achieve, given the June 14 attack on two oil tankers in the Persian Gulf which Iran calls “suspicious” but is blamed for by the US and Saudi Arabia. By aiming to de-escalate regional tensions after the Gulf attacks, Iran is hoping to build a buffer between itself and its Arab neighbors to keep them hopeful with a promise of a pact, to then reach out directly to the United States. The tactic has partially worked for now because Iran’s Arab neighbors have conveyed to German leaders touring the region that they do not seek to escalate tensions with Iran.

Even during the P5+1 talks, Iran recognized that talking with the US could throw water over agitations by Arab neighbors concerned with Tehran’s nuclear program. The Obama administration danced the dance with Iran, keeping countries like Saudi Arabia that had far deeper misgivings about Iran’s nuclear ambitions at arm’s length throughout the nuclear negotiations.

Back then, Iran also opted out the idea of discussing anything except its nuclear program with the United States, which shelved other differences including Iran’s growing regional influence and ballistic missile program. Some in Iran preferred a so-called “grand bargain” with the US that would have involved additional discussions on all issues that divided the two countries. But in conversations this author has had with an advisor to President Rouhani a year before the nuclear deal was concluded, it appeared that a “grand bargain” with the US, though desirable, would face multiple regional hurdles along the way if Iran’s Arab neighbors were to offer an endless list of grievances. Iran’s highest authorities decided to discuss with the US only what seemed to be the most negotiable item at the time: its nuclear program.

Since then, many have believed that a successful nuclear agreement would lead to Iran’s change of behavior in the region. But Tehran has never altered its foreign policy goals, unless it receives incentives to moderate some in a manner that ensures Iranian power and regional influence.

Iran is now trying to stay a step ahead once more, by using the opportunity of talks with the US as an option to de-escalate regional tensions. President Trump might believe that he is the one leading the dance here, by presenting a war-like escalation option on the table, only to then reach out to Tehran and offer phone numbers while insisting that Washington does not seek regime change. But in reality, it appears that Tehran is dancing a Waltz with President Trump, slowly and methodically mastering each step to survive.

In May, Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif took the first step, by touring Iraq, Pakistan and India. This was in tandem with Iranian diplomat and nuclear negotiator Abbas Araghchi travels to Oman, Qatar and Kuwait. On these trips, Iran encouraged its neighbors to insist on a regional de-escalation. Iran’s neighbors may not be capable of leveraging the US to reduce pressures on Tehran, but Iraq has expressed willingness to mediate the tensions.

Iran knows that it cannot fully rely on its neighbors to deter the US from taking military action against it. So it will keep engaging those neighbors for as long as it can—along with other concerned countries such as Germany and Japan whose leaders are offering to mediate tensions—without being fully clear about whether it will or will not take President Trump’s offer to re-negotiate the nuclear deal.

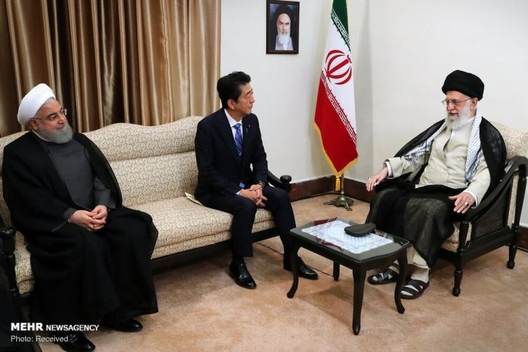

On May 29, though Rouhani suggested that future talks with the US were possible, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei dismissed the idea. The Supreme Leader repeated this during Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s visit to Tehran on June 13. However, in May, Zarif and the Iranian ambassador to the United Nations indicated Tehran’s willingness to talk to the US but not under pressure. Still, it appeared that Iran might take Japan’s advice to consider negotiating with the US without preconditions, even though for now it appears that the Japanese mediation faltered. Tehran has never liked the idea of laying out preconditions for talks in any case, which may have also triggered Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s recent statement of dropping preconditions to engage in negotiations with Iran.

Iran is also leading the second step of the dance. Rouhani has called for a national referendum to decide the fate of the JCPOA. The referendum can help Iran keep the US at arm’s length until Tehran calculates what its next moves are. The call for a referendum can rally the public behind President Rouhani if his goal is to jumpstart talks with the United States.

If these talks were to happen, Iran has learned several key lessons from North Korea’s recent talks with the US to lead the third step of the dance. Tehran has even sought Pyongyang’s advice along the way.

North Korean diplomats, according to an Iranian official this author recently spoke to, made a point of traveling to Iran to convey that the US could not be trusted when it comes to talks. Tehran clearly recognizes that solely speaking to the US is not a stable parameter to ensure success. But Tehran can buy time with Trump for as long as the US president remains unclear about his Iran policy.

For now, it seems Iran is buying time while pursuing a more aggressive nuclear policy. Though it might seem that the June 14 attacks on two tankers in the Gulf of Oman build uncertainty about the future of talks, it also gives Tehran some more time. These tactics might allow Tehran to ultimately achieve some “soft compromises” in talks with the Trump administration, including the de-escalation of regional tensions and the easing of some restrictions to allow modest trade between Iran and the rest of the world. But the dance between Iran and the US will likely go on, whether tensions further escalate or not, as the stakes are too high to get it wrong.

Banafsheh Keynoush is a foreign affairs scholar. She is also the author of Saudi Arabia and Iran: Friends or Foes?. Follow her on Twitter: @banafshkeynoush.

Image: Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in a meeting with Iran’s Supreme Leader and president (Mehr News Agency)