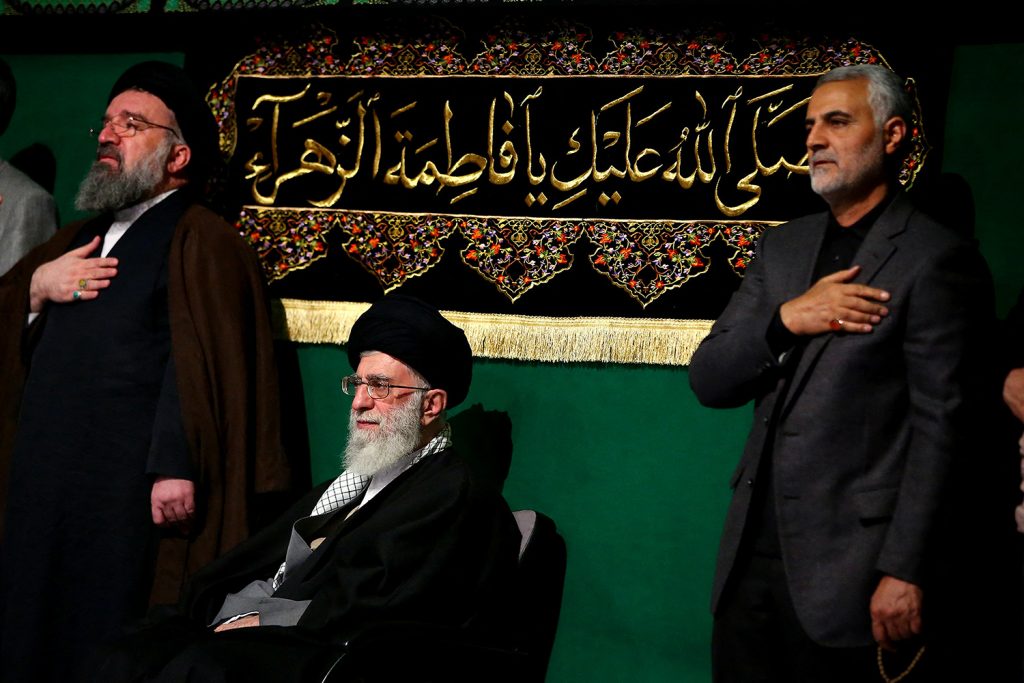

From an operational point of view, the January 2 US drone attack was a great success. In addition to Iranian General Qasem Soleimani, the United States killed Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis—a half-Iraqi and half-Iranian close associate to Soleimani and his personal friend. al-Muhandis was also a commander of Al-Hashd al Shaabi—a conglomerate of various Shia, pro-Iranian militias, present both in Iraq and Syria. A third victim was Niam Ghasem—a deputy commander of Hezbollah. Obviously target number one was Soleimani—a commander of the infamous Al-Quds, a clandestine organization responsible for Iranian activities in the region. Soleimani was, just like the whole Middle East, very ambiguous—on one hand he was responsible for the deaths of numerous US soldiers and an architect of anti-American Iran-led “axis of resistance.” On the other hand he was a person who helped destroy the Islamic State. On one hand he was beloved by many in Iraq, Iran, and Syria, while on the other he helped crush popular unrests in those countries.

The January 2 strike was a surprise and we might wonder why the United States decided to do it now. Some might point out that this was the best moment—nobody has expected this, including Soleimani and his security team. According to General David Petreaus, the Americans considered killing him around 2007. He was a natural target. Other would argue that US President Donald J. Trump wants to divert a focus from his impeachment in the Congress and therefore a military crisis—short, dangerous but victorious—is the easiest way not only to achieve that but also to win some popularity. We might see another example of a syndrome labelled by experts as “the rally ‘round the flag,” when international crisis gives leaders a popular support. At the same time other would say—and this cannot be ruled out too—that Soleimani was killed by accident and that the Americans wanted to eliminate other targets. Mistakes happen, especially when intelligence data and time to react are highly limited.

From the point of view of Iranian foreign and security strategy, Soleimani’s death is a painful failure. First of all, this harms Tehran’s reputation. If Iranian security forces are unable to protect the most important military official in the country, how can it protect other officers and Tehran’s allies in the region? Many high-rank officials in the region—from Lebanon to Yemen—must now be concerned that if the White House could kill Soleimani so easily, they can become a target too and that the Americans will not hesitate. For opponents of the Islamic Republic this is another sign of a weakness of the regime, a new lethal punch which at some point will destroy it. Authorities in Tehran solicitously care not to show any weakness. By not protecting their top general they failed to deliver such message.

Moreover, recently Iran tried to intentionally show the United States that it can play bravely—not to say carelessly—and that it is ready to take risks. Attacks against tankers in the Persian Gulf, as well as striking oil refineries in Saudi Arabia, were not met by any US reaction. This restraint—as my several unofficial talks in the Persian Gulf confirmed—was considered by regional US allies as a weakness of the United States, a sign that US security guarantees are no longer credible. At the same time, Iran pushed away a risk of war. That round of the US-Iranian war of nerves, which occurred late summer, was won by Tehran. Now, however, Trump has used Iran’s tactics of generating manageable crisis and pushed Iran into corner.

On one hand Iran cannot start an open war with the United States, while on the other it has to somehow react to save its reputation as an implacable power facing “global arrogance.” Iran can of course retaliate but first of all its capabilities are limited. Secondly, any open strike—especially if US soldiers are killed—would trigger a fierce reaction from the White House. Obviously, an open war would be a disaster for Trump—since he wants to be re-elected—but at the same time he would not be able to stay silent. A problem for the Islamic Republic is that there are many possibilities, but Tehran cannot be sure how Trump will react and which scenario is the most plausible. Moreover, they cannot make a mistake since it would be the end of their regime. Therefore, it is likely that Iran’s answer will be limited and mostly symbolic. The Islamic Republic has not reacted to Israeli bombardments of its positions in the region—from Lebanon to Syria and Iraq.

Soleimani’s death is a real problem for the Islamic Republic also for other reasons. First of all, the security apparatus has to quickly reestablish a decision-making process. Although General Esmail Ghaani—Soleimani’s successor—is very experienced, he will need time to learn and establish close personal ties with various leaders, as Soleimani had. Secondly, Iranian counterintelligence will have to find a leak inside its system. A drone attack would not be possible without reliable intelligence data. Who betrayed Soleimani? One of his aides? Or maybe someone from Hezbollah? Or maybe—and this also cannot be ruled out—the Iraqis helped the Americans to get rid of the Iranian general, who had ruled their own country for long? These are crucial questions which have to be answered by the Iranian security leadership. For sure looking after them will result in several dismissals or maybe even deaths.

A US drone attack has some consequences for Iran’s domestic politics as well. Without a doubt this is a disaster for the reformists and President Hassan Rouhani. His “peace-oriented policy” is now ultimately discredited. A decisive victory for the anti-Western, more assertive, and more military-oriented conservatives in parliamentary elections in February 2020 is now even more likely. A chance to return to the JCPOA—which is still a hope among Iranian liberals—will be finally buried. After Soleimaini’s death even some moderate Iranians will vote for the conservatives believing—maybe naively—that they are a better option for hard times that Iran is now facing.

For the Iranian conservatives Soleimani’s death is a mixed blessing. On one hand they lost a crucial pillar of Iran’s regional strategy of “axis of resistance,” which remains a cornerstone of Tehran’s foreign and security policy. As it was said, such loss cannot be replaced easily. However, this might be a good news for them as well—not only because a “martyrdom” of Soleimani will increase their chances for a good result in parliamentary elections, but also because a very powerful and popular person was eliminated—even within a close circle of trusted allies, a person who is too influential and too smart could be considered a threat. Secondly, a death of a national hero for many (not all!) Iranians adds a much-needed fuel to Tehran’s “rally ‘round the flag” strategy. This ultimate sacrifice will be put on the altar of gaining public mobilization around the regime and of diverting public attention from economic problems and mismanagement to the much-hated United States.

Robert Czulda is an assistant professor at the University of Lodz, Poland and a former visiting professor at Islamic Azad University in Iran, the University of Maryland, and National Cheng-chi University in Taiwan. He is the author of Iran 1925 – 2014: From Reza Shah to Rouhani. Follow him on Twitter: @RobertCzulda.

Image: Undated photo of Iranian general Qassem Soleimani (right), the powerful head of Iran's Quds Force, seen next to Iran Revolution Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei (center) in Teheran, Iran. He was killed in an airstrike at Baghdad International Airport, on January 2, 2020. Photo by Balkis Press/ABACAPRESS.COM