Factbox: Iran’s 2020 parliamentary elections

On February 21, the Islamic Republic of Iran will hold its eleventh parliamentary elections. These are the most uncompetitive elections in years because the Guardian Council—a vetting body of six clerics appointed by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and six jurists appointed indirectly by him—has disqualified dozens of reformist candidates, including at least eighty sitting members of parliament. With the exception of the first post-revolutionary parliamentary elections in 1980, the Islamic Republic’s parliament has only ever allowed a narrow range of politicians to run for office. But this time the Guardian Council has gone much further, effectively expelling the reformist faction of the regime from the political realm.

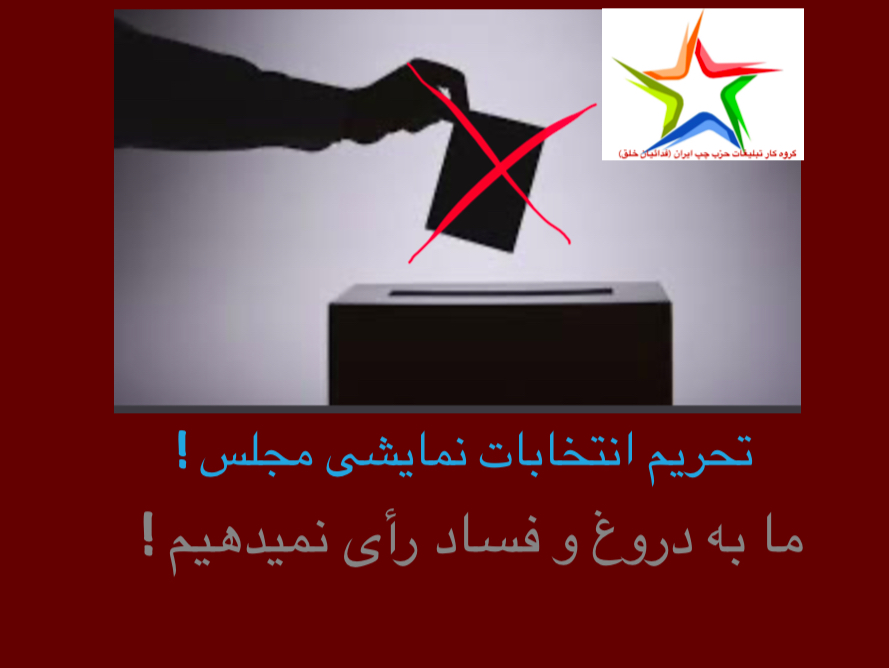

On paper, running for parliament is open to all Iranians who are between the ages of 30 and 75 years old, hold at least a Masters degree or the equivalent, have finished their mandatory military service (for men), and have shown their commitment to Islam (with the exception of those running for the five seats reserved for religious minorities). In practice, so many have been disqualified that in the majority of constituencies, there is not a single reformist contender. Mostafa Tajzadeh, a former deputy minister under the reformist President Mohammad Khatami (1997 – 2005), spoke for many when he said he would boycott the elections since they had effectively become “appointments” led by Khamenei. The High Policy Council of Reformists, representing all major reformist politicians, has declared it won’t endorse candidates in Tehran and many other provinces.

Why did Khamenei decide to further close down the political space as Iran is mired in a worsening crisis with the United States? Speculations abound but in the last few years, the Supreme Leader had repeatedly called for a parliament dominated by “young, devout and revolutionary forces”—effectively a call for a change of guards with more senior conservatives giving their place to younger elements who are usually more conservative, pro-Khamenei, anti-Western as well as supportive of Iran’s armed involvement in the Arab world.

Unless there is a last-minute intervention by the Guardian Council to admit more candidates, there isn’t much political competition in most constituencies. The guide below aims to illuminate some of the basic procedures, conflicts inside the conservative camp and the likelihood of a low turnout with meager reformist participation.

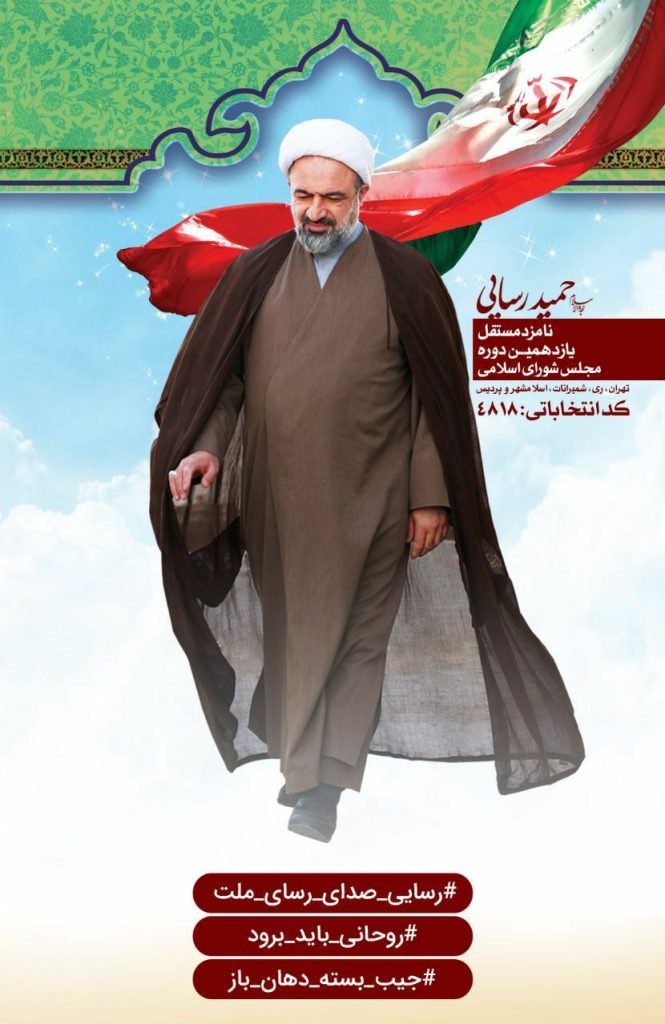

One hashtag reads: #Rouhani_Must_Go

What is the timeline?

Candidates have only seven days to campaign, a period that started on February 13. After the first round of elections on February 21, the second round will take place in May for those who reach the required threshold.

How does the election work?

More than 15,000 people applied to run for parliament. Of that number, 7,296 were disqualified from running; 7,148 candidates will compete for 290 seats across 31 provinces.

Iran is divided into single-member and multiple-member constituencies, the largest and most crucial of which is the capital Tehran, which will elect thirty MPs. All Tehranis will have a chance to vote for up to thirty candidates and the thirty with the highest vote count will get elected. There are five seats reserved for religious minorities: Jews, Zoroastrians, a shared seat for Assyrians and Chaldeans, and two for Armenians (one for Armenians in the north, one for those in the south.)

What is the regional distribution?

Tehran province elects thirty-five MPs, the most out of Iran’s thirty-one provinces. This is followed by Esfahan and Eastern Azerbaijan with nineteen MPs each. The least number of MPs are elected by Alborz, Qom, Ilam and Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad provinces which each choose three MPs.

On average, every 190,000 Iranians elect a MP. The current parliament rejected a bill that would have increased the number of seats. It’s worth noting that there is some discrepancy in regional representation: Semnan, which happens to be the home province of President Hassan Rouhani, elects one MP for every 123,000 voters. The most underrepresented province is Alborz, centered around the city of Karaj, which grew from a suburb of Tehran and has now become a mammoth conurbation. The province elects one MP for every 493,000 voters.

Who is not running?

Even before the Guardian Council disqualified dozens of sitting MPs, many parliamentary veterans decided not to run again. Chief among them was Parvaneh Salahshouri, a one-term reformist MP representing Tehran who made her name by a rare and courageous defense of November 2019 protests that followed a sudden increase in the price of gasoline. Also not running is Ali Larijani, a Qom MP from an influential family, who is also a former nuclear negotiator and the speaker of the parliament since 2008. Mohammad Reza Aref, head of the pro-Rouhani Hope Faction in the parliament, also refused to run.

The Guardian Council went on to disqualify some of the best-known MPs from Tehran such as Mahmoud Sadeghi, a popular MP known for his outspoken defense of civic rights, and Ali Motahari, a conservative but pro-Rouhani MP who was also popular with many reformists (he is the son of Ayatollah Motahari, the chief ideologue of the Islamic Revolution who was assassinated in 1980.)

Narges Mohammadi, a human rights activist who is imprisoned in Tehran’s Evin prison since 2014, is among many civil society actors who have called for a boycott of the parliamentary elections to protest “killings on the street and the government’s cruel response.”

Are there political parties in the parliament?

Yes and no. There are numerous political parties in Iran but they don’t have a formalized presence in the parliament and their names don’t appear on the ballot. Politicians also don’t necessarily follow the lead of their parties. Most people vote on the basis of ‘lists’—endorsements offered by political coalitions and civil society groups. A single politician can be on many different lists. The voter can, of course, chose whether to vote for candidates on a particular list or mix and match as, aforementioned, there are no ‘lists’ on the ballot, and the name of individual candidates needs to be written.

What will Rouhani and reformists do?

President Rouhani is considered to be not a reformist but more of a centrist. His Moderation and Development Party has called on the Iranian people to take part in the parliamentary elections, despite the fact that the president criticized the disqualification of a large number of candidates.

Main reformist parties—such as the Islamic Iran’s Participation Front (IIPF) and Organization for the Mojahedin of the Islamic Revolution of Iran (OMIII) —were banned in 2010 due to their support for the 2009 post-election protests known as the Green Movement. An umbrella reformist party, Islamic Iran’s Unity of the Nation Party (IIUNP), was formed in 2015 but it has also faced repression and seemingly none of its members were allowed to run this time around.

The High Policy Council of Reformists (HPCR) did declare that it won’t endorse anyone in Tehran and some other provinces but constituent reformist parties will run their own candidates and might offer their own lists. This was being finalized at the time of writing. Executives of Construction Party (ECP), a reformist party which historically represented the followers of late president, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, has said that it will probably declare a list of twenty people for Tehran (i.e. asking Iranians to vote for only twenty out of the possible thirty.) The list will be headed by the most prominent reformist allowed to run, Majid Ansari. The 66-year-old cleric is the head of the Assembly of Militant Clerics (AMC), the traditional home of pro-reform clerics in Iran. He has served as a vice president to both Rouhani and Khatami and is currently a member of the Expediency Council, a body tasked with resolving disputes between the parliament and the Guardian Council. The most well-known reformist in Iran, former President Khatami, is yet to declare his position on the elections.

But reformists will most decidedly be a very small minority in the next parliament and Rouhani will have to deal with a conservative-dominated parliament for the remainder of his term. According to a calculation by Abdolvahed Mousavi Lari, HPCR’s deputy head, 160 of 290 seats around the country will see next to no competition, even inside the conservative camp.

What are the main conservative forces?

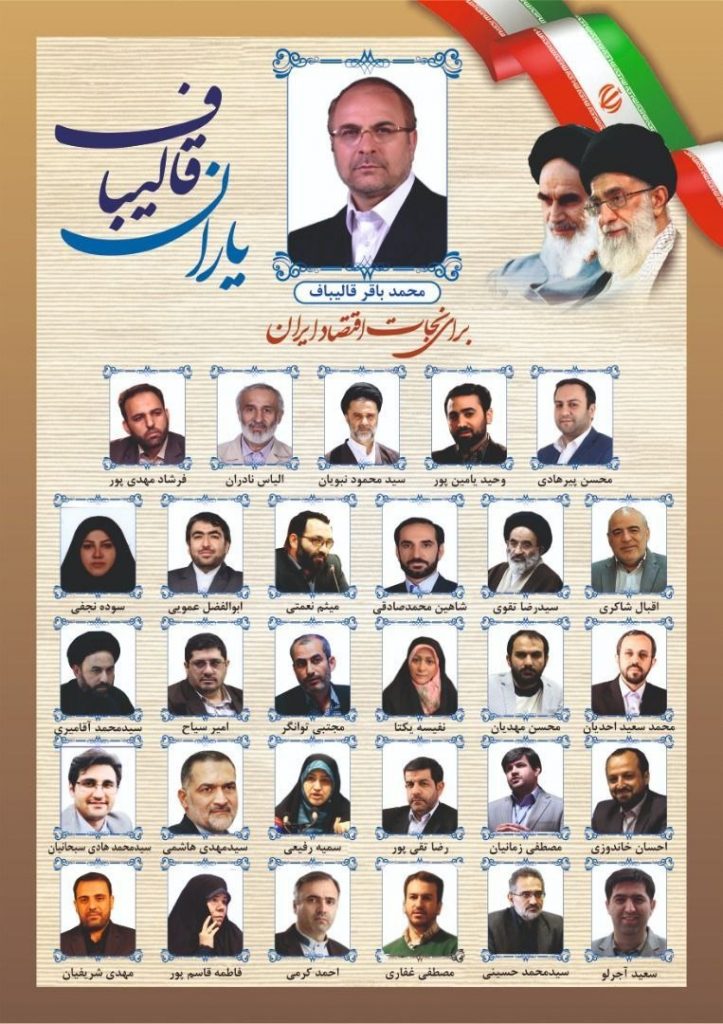

The conservative camp of Iranian politics, known as principlists, is notorious for its many divisions. Constant attempts at bringing unity have always failed and they’ve rarely been able to unite around one presidential candidate. The main divisions are usually over the relative weight of technocrats and ideologues or particular polarizing personalities like former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad or former Tehran mayor, Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf.

Qalibaf is perhaps the most talked about candidate this time around. Having failed multiple times as a presidential candidate, the 58-year-old ambitious technocrat wants to use the parliament to re-launch his bid for power in the new era. A wily politician, Qalibaf sees himself above the divisions inside the conservative camp and has tried to run a populist campaign based on promises to solve people’s dire economic woes.

The latest iteration of conservative attempts at unity took place in November 2019 with the formation of Council for the Coalition of the Forces of the Islamic Revolution (CCFII), which brings together Qalibaf’s Islamic Iran’s Society for Progress and Justice (IISPJ) with other parties such as the Society of Devotees of the Islamic Revolution (SDII), founded by controversial ultraconservative Tehran MP Alireza Zakani who was known as a strident critic of the 2015 Iran nuclear agreement. Also in the CCFII is the Isargaran Society (IS), consisting of many former supporters of Ahmadinejad who broke with the president after he came into conflict with Khamenei.

The main rival to CCFII is the Islamic Revolution’s Endurance Front (IIEF), founded in 2011 and consisting of ultraconservatives inspired by Ayatollah Mesbah Yazdi, Qom’s most stridently conservative figure. Headed by Morteza Agha Tehrani, a cleric who made his name as the conservative Imam of a mosque in New York, IIEF is known for unquestionable devotion to Khamenei and militant opposition to all reformists and the Rouhani government. Qalibaf tried hard to unite with IIEF and offer a united conservative list for key constituencies like Tehran, but failed in the end. IIEF published its own list which does not include Qalibaf, who will now head the CCFII’s list.

Ahmadinejad continues to be outside the main political realm since most of his followers were barred from running. His political movement known as the Spring continues to be marginal and his two closest political allies, Esfandiar Rahim Mashaei and Hamid Baghaei, remain behind bars.

Arash Azizi is a New York-based writer and academic. He previously co-hosted a program on London-based Manoto TV, which was one of the most watched news shows in Iran, and was a former international editor of Kargozaran, an Iranian daily. He is currently a doctoral student at New York University, where he researches the history of the Middle East during the Cold War. Follow him on Twitter: @arash_tehran.

Image: Iran's parliamentary elections graphic (IRNA)