President Trump has threatened to unilaterally withdraw from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in May if his demands for “fixing” the deal are not met by Britain, France and Germany (the E3). Iran has categorically rejected any amendments to the nuclear agreement and has argued that it has a range of options to respond if Trump carries out his threat.

President Trump has threatened to unilaterally withdraw from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in May if his demands for “fixing” the deal are not met by Britain, France and Germany (the E3). Iran has categorically rejected any amendments to the nuclear agreement and has argued that it has a range of options to respond if Trump carries out his threat.

Iran’s optimal strategy would be to respond in a way that would mitigate domestic uproar and to the extent possible, protect the country from repercussions. Iran’s national security establishment seems to have come to a strategic decision to stay in the deal if the other parties do and try to isolate and outmaneuver Washington. Therefore, it seems unlikely that Iran would abrogate the JCPOA in its entirety. Rather, it may decide to take limited measures to demonstrate a level of strength and to test the international community’s response.

It is important to point out that Iran’s reaction depends on the manner in which the US withdraws. In a worse case scenario, the US would re-impose and seek to enforce previously waived secondary sanctions. This would be a coup de grâce to the JCPOA and provoke an uproar and potential commercial or other retaliation from European allies who played a significant role in establishing the sanctions regime and reaching the 2015 agreement. It is also possible that the US withdraws but does not enforce the nuclear-related sanctions. This would be a less hostile approach because it would leave room for diplomatic maneuvers.

One possible response to a US withdrawal would be for Iran to declare that it will no longer implement the Additional Protocol of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. This supplementary protocol significantly enhances the ability of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to monitor and verify Iran’s compliance with the JCPOA.

Under the agreement, Iran is required to implement the protocol and to ratify it within eight years of the January 2016 implementation of the JCPOA. If the deal collapses, Iran will no longer feel obliged to allow the intrusive inspections required by the protocol or to ratify it. This would significantly reduce the IAEA’s ability to monitor Iran’s nuclear activities. However, this seems to be a relatively safe option for Iran, since implementation of the protocol is on a voluntary basis. Iran had previously implemented the protocol from 2003 to 2005, when it negotiated with the E3 and briefly suspended its uranium enrichment program.

It is also likely that Iran and the other signatories to the JCPOA will continue implementing the nuclear deal without US participation. The IAEA and the European Union have repeatedly stated that Iran is abiding by the JCPOA and there is no need to scrap an international agreement that is working. By engaging the EU countries, Iran can widen the gap between the US and its traditional allies created by previous US actions such as leaving the Paris climate accords, denigrating NATO and threatening tariffs on steel and other products. This will be a diplomatic victory for Iran, diverting blame toward the United States.

Iran’s announcement that it will not increase the range of its missiles beyond 2000 kilometers can be interpreted as a signal to European countries that it does not seek confrontation with them.

There are, of course, other more escalatory options for Iran. It could, for example, opt to resume some of its past nuclear activities that are limited by the JCPOA, such as the requirement that Iran not enrich uranium beyond 3.67 percent of the isotope U-235 and maintain a stockpile of low-enriched uranium no larger than 300 kilograms (a quarter of what would be required for a single nuclear weapon if it were further refined to weapons grade).

Iran could resume enrichment at the 20 percent level, still below weapons grade. Ali Akbar Salehi, the head of Iran’s Atomic Energy Organization, recently announced that Iran could resume enriching at 20 percent within a few days if the US violates the JCPOA. Iran uses 20 percent enriched uranium as fuel for the Tehran Research Reactor, which produces medical isotopes.

Iran has also informed the IAEA that it plans to design nuclear propulsion reactors for naval vessels. However, it is unlikely that Iran will actually begin constructing them for at least two reasons. First, Iran would need to enrich uranium at a much higher level of 60 percent. Iran has the technological capacity to enrich to that level, but this would certainly raise alarms in the West because it is not very far from 90 percent, which is weapons grade. Secondly, Iran’s navy has traditionally been its smallest force and it is not economical for Iran to invest in such a costly endeavor for such a force.

Other options for Iran would be to begin installing more advanced centrifuges at Natanz or, very provocatively, resume enriching uranium at its underground facility at Fordow.

Iran’s reaction to any US decision to withdraw from the deal will most likely be made by the Supreme National Security Council, a body that includes representatives of all the main security institutions in Iran, with a final approval from Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. If the US abrogates the JCPOA in May, President Hassan Rouhani and his team will be under tremendous pressure from hardliners to respond.

It is the judgment of this analyst that Iran will initially pursue a course with the fewest diplomatic repercussions and try to remain within the agreement to outflank and isolate the United States. But the danger for escalation remains.

Sina Azodi is a PhD student in Political Science and a graduate researcher at University of South Florida’s Center for Strategic and Diplomatic Studies. He received his BA and MA from the Elliott School of International Affairs, George Washington University. He focuses on Iran’s foreign policy and US-Iran relations. Follow him on Twitter @azodiac83

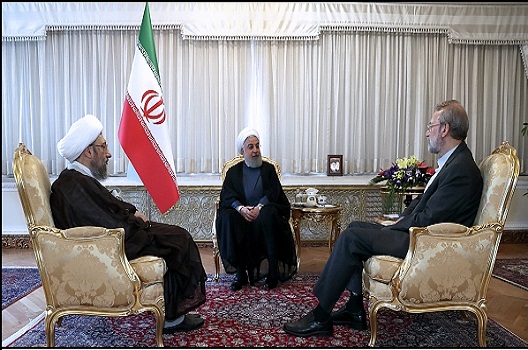

Image: Meeting of the heads of the three branches of the state.