How Iran’s interpretation of the world order affects its foreign policy

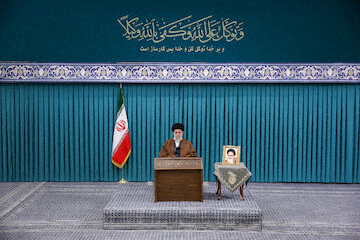

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei sets the overall direction of the country, so understanding the psychological milieu of the leader and the political establishment is important in interpreting and anticipating Iran’s foreign policy.

Khamenei was considered a pragmatist before he became leader in 1989, according to a CIA report published in 1986. However, in office, he took the views of radical Iranian leftists, adopting extremist slogans against the west and the United States. Khamenei, who was from the right-wing, abandoned pragmatism in foreign policy to weaken left-wing rivals and get the support of Iran’s security establishment—particularly the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC)—after being appointed leader of Iran in June 1989. In going along with the hardcore faction of power, he consolidated his position.

His view of the international order is based on three axes of global power. The first—the liberal order based on institutions and laws created after World War II—is weakening in his view because American hegemony is declining. A second axis, formed by Russia and China, is seen as rising. The third axis joins Iran with this rising new world order with Moscow and Beijing, adopting a policy of “look to the East,” and abandoning the old slogan of “Neither East, nor West” that was dominant after the 1979 revolution.

On April 26, in a meeting with students, Khamenei said: “Today, the world is on the threshold of a new international order, which, after the era of bipolar world order and the theory of unipolar world order, is taking shape. In [the] current period, of course, the US has become weaker day by day.”

Referring to American theorists such as Stephen Walt, who also see the decline of US primacy, Khamenei said in 2019: “Some American experts and thinkers have used the term ‘termite-like decline’ in describing the political, social, and economic situation of this country.”

The US economy now accounts for less than a quarter of world GDP, down from a 40 percent share in 1960. US military spending is still huge, accounting for almost 40 percent of the world’s total military spending in 2020, but the US is no longer seen as the sole global hegemon.

American thinkers such as Joseph Nye see a decline of the liberal order as countries such as China exploit their membership in the World Trade Organization. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, this order was challenged by the rise of China and populism in Western democracies. Once champions of globalization, the US and Europe are now seeking to counter this trend.

“Although the US has long commanded the technological cutting edge, China is mounting a credible challenge in key areas,” according to Nye. “But, ultimately, the balance of power will be decided not by technological development but by diplomacy and strategic choices, both at home and abroad.”

Foad Izadi, a well-known Iranian theorist and professor at Tehran University, shares the view that the US is declining “due to structural weaknesses in its economic foundations. As America’s pillars and foundations become weaker, so does the strength of these pillars.”

Izadi also said recently: “We are witnessing the decline of the United States in various areas, including social and economic. This situation is not reversible and unstoppable. Many of the world’s problems will be solved with the decline of the United States.”

Despite Russia’s poor military performance in Ukraine and the at least temporary reinvigoration of NATO, Iranian officials still assert that the Russian invasion of Ukraine was a sign of the US losing strength. This was echoed by Khamenei recently on April 26, when he said, “The issues of the recent war in Ukraine should be seen more deeply and in the context of the formation of a new world order.”

The Iranian establishment also believes that there has been a decline in the liberal order amid a rise of populism and far-right currents in Western democracies.

The establishment uses these views to justify closer relations with Russia and China to a skeptical population, especially after intensifying criticism of the twenty-five-year agreement with China and twenty-year agreement with Russia (which hasn’t been finalized).

Critics note that while China’s rise has been substantial, its power in the future shouldn’t be exaggerated. The US will remain strong for the foreseeable future, with the world’s second-largest and most dynamic and networked economy, even if China’s GDP becomes larger.

It should be noted that the continuation of high economic growth and taking steps in the field of political development without basic fiscal, financial, and other market reforms isn’t possible. As Rhodium Group’s Daniel H. Rosen notes in Foreign Affairs, “China is relatively poor. Per capita income in China is about one-fifth of that in the United States, at around $12,000 a year. Nine hundred million Chinese citizens are not yet living comfortable urban lives and are waiting for their turn.” The problems of 2022, which will be an economically bad year for China, are expected to cast a shadow over the country’s economy for many years to come.

Regarding the second axis—namely, a future world system based on Russia and China as new poles—this approach reflects the Islamic idealist and leftist nature of the 1979 Iran revolution.

At the beginning of the revolution, the new regime sought to disrupt the international system. But following the devastating Iran–Iraq War of the 1980s, Iran faced limitations that jeopardized the survival of the regime and forced them to adjust to new structural constraints.

In the 1990s, the Islamic Republic sought to integrate into the international system. However, the failed efforts to de-escalate tensions with the West in the Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani—who pushed for a China-like model—and Mohammad Khatami administrations, as well as the Western bloc’s unprecedented economic pressure on Iran, led Tehran to pursue strategic cooperation with US rivals.

The recent Iran-China cooperation document and Iran-Russia agreement can be seen in this light.

Iran’s “Look to the East” policy seeks to use Russia and China to bolster Iran, especially on the nuclear issue, and to withstand Western sanctions and threats. But, in practice, Russia and China don’t always support Iran in the United Nations and even showed some relative compliance with US unilateral sanctions during the Donald Trump administration.

The “look to the East” policy also has domestic implications, reinforcing a uniform political and social structure and leading to the erosion of the middle class.

Reformists who back a “look to the West” view have been largely eliminated from the Iranian political structure and it is practically impossible for them to return to power, as former Iranian President Khatami recently acknowledged.

In promoting the third axis of Iran, Russia, and China, Khamenei stresses that cooperation isn’t limited to trade and economic relations and includes military ties. The recent visit of China’s defense minister, which was depicted as an extension of the Tehran-Beijing twenty-five-year document, is significant in this regard.

Iran’s establishment sees the US adoption of “offshore balancing” and gradual withdrawal from the Middle East as the harbinger of a new order in the region that entails more and more cooperation with China.

In conclusion, there is a gap between the psychological milieu of Iranian political elites and the real-world balance of power. This may cause Iranian foreign policy to be less successful, but will strengthen conservatives in the political system and their supporters at the community level. Thus, the psychology of Iran’s foreign political decision-makers should be assessed from the perspective of domestic politics and the protection of the interests of the ruling elite.

Javad Heiran-Nia is director of the Persian Gulf Studies Group at the Center for Scientific Research and Middle East Strategic Studies in Iran. Follow him on Twitter: @J_Heirannia.

Further reading

Tue, Apr 5, 2022

The potential side benefits of a revived JCPOA for Middle East stability

IranSource By Barbara Slavin

If there is to be any chance of recalibrating this policy after Khamenei dies, as many inside Iran and outside it would like to see, reviving the JCPOA is a necessary first step.

Wed, Nov 24, 2021

How Iran sees the Biden doctrine for the JCPOA and Persian Gulf

IranSource By

Iranian experts in Tehran see the Joe Biden administration's approach toward Iran and the JCPOA in the context of his government's overall foreign policy and its desire to extricate itself from military conflicts in the Persian Gulf.

Tue, Feb 1, 2022

Can President Ebrahim Raisi turn Iran’s economic Titanic around?

IranSource By Nadereh Chamlou

The Ebrahim Raisi team is seen as the weakest since the revolution, but one with the strongest links to the IRGC, and where allegiance trumps expertise.

Image: Iranian women hold a picture of the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and the Iranian flag, during the celebration of the 43rd anniversary of the Islamic Revolution in Tehran, Iran February 11, 2022. Majid Asgaripour/WANA (West Asia News Agency) via REUTERS