Can President Ebrahim Raisi turn Iran’s economic Titanic around?

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei met on January 30 with a group of industrialists and producers. He complained about the country’s economic situation and blamed government policies over the past decade for the rising inflation and inadequate quality of some domestic products. But the Islamic Republic’s economic troubles began decades ago with post-revolutionary domestic and foreign policies that put the country on the wrong foot from the start.

The passing of the country’s first president, Abolhassan Banisadr, last October in France—where he spent much of his life first opposing the Shah and then the Islamic Republic—caused a flurry of post-mortem analyses about his legacy. This Sorbonne-trained economist became president in February 1980, backed by the founder of the Islamic Republic, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, and 75 percent of the popular vote, but was impeached eighteen months later and fled back to France for fear of his life. Yet, in the Petri dish of post-revolutionary ideas, Banisadr’s short tenure was long enough to implement his questionable theory of a “monotheistic economy”—a blend of Marxist and Islamic concepts.

The revolutionaries confiscated 2,200 enterprises, transferred key industries to state-controlled foundations, and eliminated the pre-1979 industrial entrepreneurial class through expropriation, exile, or execution. One of the most harmful actions within the new economic order was adopting Article 44 of the new Constitution, which called for nearly all meaningful large-scale economic activities to be publicly-owned and administered by the state. It became such a ball and chain for the private sector that its revision was debated for decades. Privatizing state-owned enterprises in any country is always tricky, and Iran’s early effort to test waters was no different. The manner in which batches of assets were divested created a public perception that, as the Tehran Times wrote in 1998, “a number of healthy public industries were transferred to handpicked persons at peanut prices.” When finally, Article 44 was amended in 2004, it removed some barriers to the participation of the private sector in key segments of the economy.

However, from 2009 onward, state ownership was replaced by a complex web of parastatal organizations, banks, cooperatives, pension funds, and foundations tied to military-linked companies, which were assigned large publicly funded projects. This subcontractor class has since shaped the politics of the Islamic Republic and has stymied the independent private sector, which functions mainly in the margins—at the most on a small to medium scale.

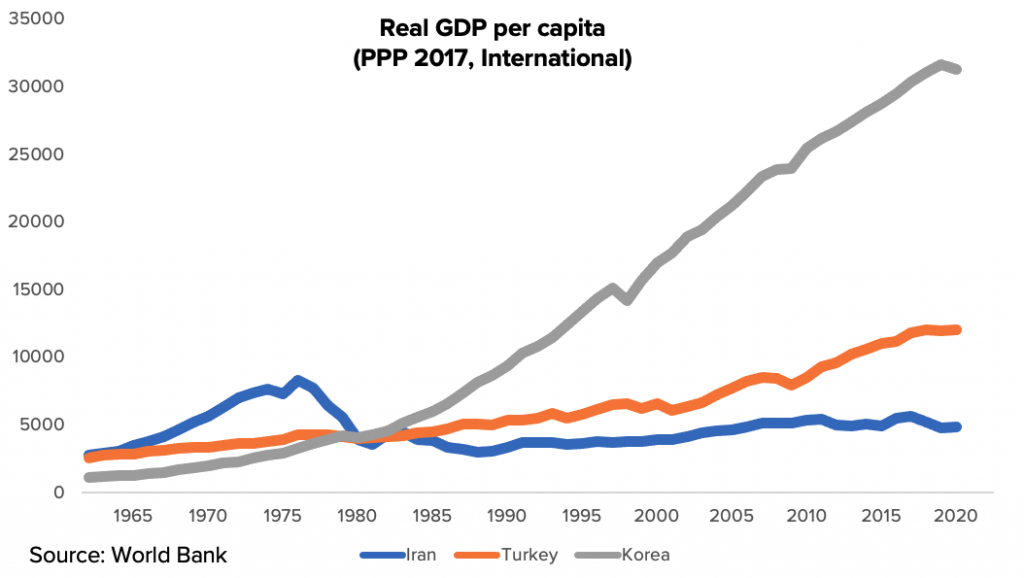

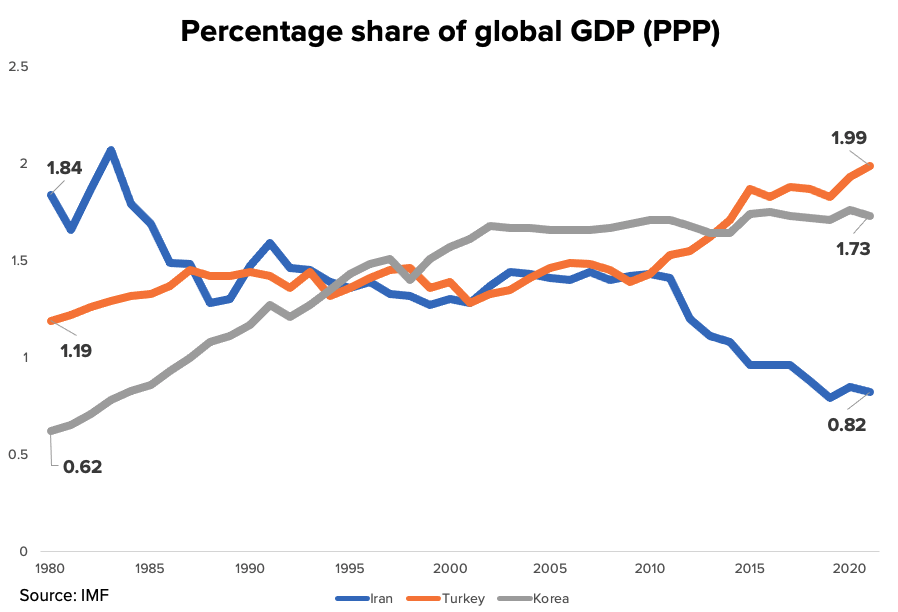

The figures below summarize the Islamic Republic’s report card over the past decade as a consequence of these policies. According to the International Monetary Fund, Iran’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP)—based on Purchasing Power Parity (PPP)—accounted for 1.86 percent of the world’s GDP (PPP) in 1980. By 2021, its share had declined to 0.8 percent. Within the same timeframe, South Korea’s share rose from 0.6 to 1.7 percent and Turkey’s from 1.2 to 2 percent. This means that Iran has lost considerable economic power on the global stage in comparison to where it was in 1980. Economic underperformance combined with a near trebling of Iran’s population has also led to a per capita income that has barely grown in three decades and one that falls short of its comparators.

Low growth, high inflation, and widespread un- or underemployment have diminished the purchasing power of many income deciles, causing widening income inequality. Iranians below the national poverty line have doubled in the past three years, now encompassing 35 percent of the population. There are daily reports of a decline in the purchase of basic food staples, such as a 50 percent drop in meat, dairy, eggs, and fruits. Even more affordable imported rice, rather than the domestic variety, is being sold one cup at a time rather than in bulk as was done before. There is a shortage of affordable housing, and an average of 40 percent of Iranians—and as high as 70 percent in Tehran—are “house-poor,” i.e. spend the lion’s share of their income on housing, leaving them exposed to sudden poverty in case of cost of living shocks. The anxiety about an ever-increasing uncertain future has also created a mental health crisis.

Unemployment among the educated youth is as high as 40 percent, and one in three Iranians is eager to emigrate. Since the revolution, Iran has become a leading country in brain drain. For instance, in just one category and in 1399 alone (the last Iranian calendar year: March 2019-March 2020), some 250,000 nurses left Iran. It’s a critical number for a country with one of the earliest and worst coronavirus outbreaks in the Middle East. Supreme Leader Khamenei has weighed in by issuing a stern warning against those who encourage the skilled to emigrate, calling it treason.

Officials are quick to blame Iran’s economic underperformance on decades of sanctions imposed by the United States, which have indeed impacted and distorted Iran’s economy. Yet, a 2021 paper co-authored by Hashem Pesaran, Iran’s most renowned economist, faults predominantly domestic policies. The study examines foreign exchange fluctuations and output growth as the leading indicators since 1989. It finds that 80 percent of foreign exchange fluctuations and 83 percent of variations in output growth cannot be explained by sanctions. These “most likely relate to many other latent factors that drive the Iranian economy,” writes Pesaran. Indeed, “state-dominated institutions, heavy-handed bureaucracy, and a banking sector plagued with problems are Iran’s self-imposed sanctions,” concurs Roozbeh Pirouz, a British-Iranian entrepreneur.

The Islamic Republic’s economic model, as designed and implemented by its founders, has failed to fulfill in the last forty-three years any of the grandiose promises that Ayatollah Khomeini made to the Iranian people, such as affordable housing, free utilities, and the eradication of poverty.

The revolution’s second phase

Months into a new century (the current Iranian calendar year 1400, March 2021-March 2022), a new administration took office. In June 2021, Ebrahim Raisi became president with the lowest voter turnout in the Islamic Republic’s history in a tightly engineered race. Thus, the regime has achieved its goal of putting hardliners in control of every branch of the state. The Supreme Leader declared the new era as the “Revolution’s Second Phase,” a period to complete the unfinished business of reaching self-reliance and renewing the social and cultural order.

President Raisi inherited an economy constrained by the regime’s mismanagement, external sanctions, and a global pandemic. Still, his predecessor’s administration managed to hand over an economy, which according to the World Bank, had rebounded from its -6.8 percent decline in 2019 to register a 3.1 percent growth for 2021. However, average unemployment remained at 10 percent—and much higher for women despite a marked decline in the female labor force participation rate (from 18 percent to 14 percent). Government debt was at 33 percent of GDP, and inflation ran at 58 percent—the highest since World War II when the Allied Forces invaded and occupied Iran between 1941-1945.

Despite the formidable challenge of lifting sanctions by reviving the 2015 nuclear deal, Raisi promised four million housing units in four years, one million new jobs per year, single-digit inflation, and a unified exchange rate. A tall order under any circumstances.

The first step for any credible administration is to appoint the right people for the right jobs, then announce relevant policies and allocate adequate budgets for implementation. Judging by his first six months in office, it’s hard to see how Raisi can succeed.

A cabinet of questionable competence

The Raisi team demonstrates several characteristics. For one, he has appointed nine ministers from the Mahmoud Ahmadinejad government—a team that was largely seen as inept and the cause of Iran’s current internal and external challenges, despite high oil windfalls during its tenure (2005-2013). More than any of his predecessors, Raisi recruited a preponderance of veterans of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) not just at the cabinet level (currently eight ministers), but also deputies, managers, mayors, and governors.

Unlike the Hassan Rouhani cabinet, which boasted more PhDs from US universities than its concurrent Barack Obama administration, many of Raisi’s ministers are graduates of Imam Sadeq University—not one of Iran’s leading academic institutions and one that has seen its role largely as “Islamizing” the humanities and social sciences. Despite its debatable academic standing, it’s in high demand because it’s a pipeline to high posts in the regime, thus earning the nickname of Iran’s Harvard, where entrants must pass an ideological loyalty test. The increased reliance on graduates from this and similar institutions, which have mushroomed, signals the rise of a new power class of fundamentalists.

Nepotism and cronyism have been rampant in the Islamic Republic, but it has reached new heights, with many regime insiders giving their sons-in-law high-ranking positions. Critics turned the topic of the rule of the sons-in-law into a trending hashtag (داماد_سالاری#) and have challenged Raisi and the speaker of the parliament, Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf, during recent public appearances.

A further facet of the new administration is that many ministers have been assigned to portfolios for which they were least suited. Several nominees were confused about which ministry they were to head when making their case to parliamentarians, who complained about the choices, but in the end approved all but one.

In short, the Raisi team is seen as the weakest since the revolution, but one with the strongest links to the IRGC, and where allegiance trumps expertise. Despite its “group-think” appearance, subgroups represent different hardline factions. Sooner or later, their economic and political interests are bound to diverge or clash, thus further undermining the Raisi government.

Iran’s budget assumptions, revenue sources, and expenditures

All eyes are now on the nuclear talks in Vienna to see if the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) can be resuscitated, and if Iran can remove as many sanctions as possible. The Iranian currency, the rial, has depreciated by about 15 percent against the US dollar since Raisi took over. It also broke through the psychological ceiling of 300,000 rials to the dollar, oscillating up and down depending on signals and rumors from Vienna. Around the country, there are near-daily demonstrations by various groups—from farmers to teachers—protesting the rapid rise of the cost of living.

So far, however, decision makers have seen more urgency in tackling such issues as reversing Iran’s anemic birth rate, legislating rules to forbid pets, and planning on how to limit access to the Internet.

On December 12, 2021, Raisi submitted a draft budget to parliament, which is useful in assessing the government’s vision about meeting the challenges ahead. Some of the key assumptions are the expected oil revenues, fate of the preferential exchange rate of 42,000 rials per US dollar, level of cash subsidies, size of the deficit, methods to fill the budget gap, who benefits, and who foots the bill.

Iran’s 1401 (March 2022-2023) budget is 36,310 trillion rials ($121 billion at the market rate), including the budget for state enterprises and $50 billion for general government expenditures. It’s nominally 46 percent higher than the last Rouhani government budget, but, considering inflation, it’s contractionary in some parts. It assumes an 8 percent GDP growth rate even in the absence of any sanctions relief, hence the claim that sanctions’ impact on the Iranian economy will have been neutralized. Whether that is so, is much in doubt.

Oil exports in the budget are projected to be around 1.2 million barrels per day (bpd) at U$55-$60 per barrel. This is below the 3.8 million bpd Iran exported before the US withdrawal from the JCPOA in 2018. But, it may be reasonable since, according to the Financial Times, Iran’s exports rose to 2.4 million bpd during January-November of 2021.

Noteworthy is the government’s resolve to phase out the preferential exchange rate of 42,000 rials per US dollar, which was supposed to buffer price hikes for key consumption items. Instead, the preferential rate led to corruption and rent-seeking—thus distorting the economy rather than protecting the vulnerable. This rate applied to some 1,200 items, not all considered necessities. Its use will now be restricted to a few items, such as wheat and, possibly, medicines, although the latter is still being debated. Unifying the exchange rate would undoubtedly lead to inflation because of the higher cost of many imported goods.

Another policy decision concerns subsidies—how much and to whom. There will be three types of cash subsidies. Using the market exchange rate of 300,000 rials per US dollar for convenience purposes, two of the subsidies will amount to about $3 per month, and all Iranians are eligible. The third subsidy is targeted toward the seven lower income deciles. Individuals in the lowest four deciles, the “poor”—those with a monthly income of less than $120 per person—receive $4 per month; those in the fifth, sixth, and seventh decile, the “middle class”—a monthly income of $120-$180—get $3. While the share of the population in each category hasn’t yet been determined, it could be said that a “poor” household of four can receive a total of around $28-$30 from the various cash subsidy schemes, and a “middle class” household around $25 per month.

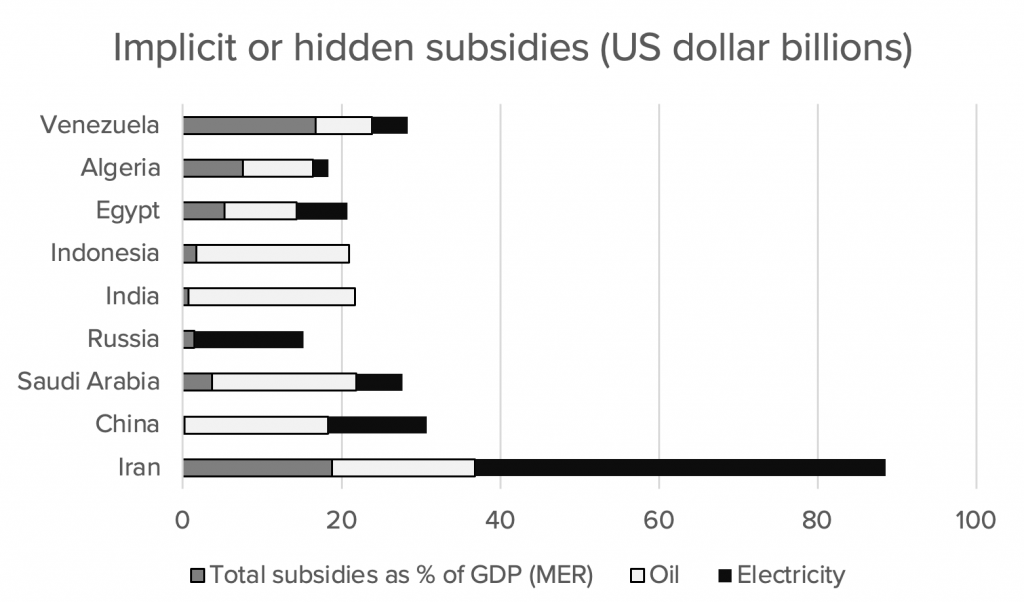

Cash subsidies are transparent and deposited each month into people’s bank accounts. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), there is a host of other implicit or hidden subsidies amounting to around 19 percent of the GDP per year. These consist of below market prices for oil, electricity, and gas. Iran ranks highest in terms of such payments (see below). Unlike the cash subsidies targeted toward lower income deciles, the rich benefit from these subsidies because they consume more. There have been many debates and studies on their impact and how to possibly phase them out or target them better. No solution has been found so far. Reducing or removing such subsidies will undoubtedly impact many producers as well, whose viability has for long depended on low energy costs.

Domestic and external oil and gas revenues are projected to increase by 9 percent over the previous budget year. In addition to higher export volume and price assumptions, each Iranian receives a 15 liter per month fuel allocation; any consumption beyond this amount will be at market prices, which will generate income for the government. Frugal users can resell their allotments to others—effectively creating a secondary market that may benefit low-income families, who are typically low users of such resources. Nevertheless, its overall impact would be a rise in transportation costs—be it through the repurchase of allocations or free market sales—and an inflationary ripple effect across the economy.

Tax revenues will cover the bulk of the expenditures, which are expected to increase by 61 percent compared to the 1400 budget year. The source of the increase will have to come from a 126 percent jump in tax collection from businesses and “legal persons” (IRGC-related units are exempt), 55 percent from salaried individuals, 43 percent from import duties, 64 percent from taxes on goods and services, as well as a 68 percent increase from a value-added tax.

Relying on tax-based revenues is not bad per se. But in difficult times, governments usually tax those with more disposable means. Curiously, though, revenues from wealth taxes are expected to decline by 20 percent. This happens not only at a time of growing income inequality, but also when Forbes Magazine reports that during the pandemic, “the number of high net worth individuals in Iran grew by 21.6 percent, way above the global average of 6.3 percent,” adding that “the collective wealth of these dollar millionaires grew even faster at 24.3 percent.” This suggests that one class of people is doing extremely well. Hence, it’s understandable for average citizens to feel that the regime is emptying their wallets and shielding the rich “insiders,” particularly when an October 2021 motion requiring officials to declare their assets before and after their tenure was defeated on the basis that such information constitutes “state secrets.”

The combination of high inflation and these higher taxes impact the middle class disproportionately more, and as Pesaran warns, Iran is likely to become an economically more polarized society. Evidence shows that as the middle class expands, so do ideals of democracy, freedom, and secularism, values that may conflict with the social and cultural goals of the second phase of the Islamic revolution.

About two-thirds of the current proposed budget will be for salaries, which assumes a 10 percent average increase—considerably lower than expected inflation. Another item is the replenishment of pension funds on the order of $7 billion; a similar amount goes for servicing government debt. It’s unclear how much of the budget is geared toward development—or production—possibly embedded into the budgets of relevant line ministries. This suggests that the funds are more destined for consumption than toward investments in the future.

With roughly 10-15 percent of Iran’s population, Tehran receives the highest regional budget allocation. Thereafter comes Isfahan and Khuzestan, not the next most populous provinces, but the ones in which the regime has witnessed worrisome demonstrations linked to water shortages and livelihoods.

Among the budget items that have raised eyebrows is a 2.4 fold increase in funds for the IRGC, whose mission is to protect the Islamic Revolution. The task of protecting the country falls on the traditional military, which is to receive around a 50 percent increase—keeping up with inflation. Regime publicity organs, such as the broadcasting corporation and a slew of religious/ideological centers, are to receive generous provisions, often above those of traditional line ministries. For instance, just one entity, the Center for Seminary Services, is to receive 1.5 times the budget of the Environmental Protection Agency, despite Iran’s formidable climate change challenges. Beyond the Ministry for Islamic Enlightenment, the budgets of at least a half dozen other separate religious propaganda entities are also enshrined in the proposal. These allocations are, of course, used to proselytize the kind of Islamic culture and ideology preferred by the regime. One example is the establishment of eleven thousand Islamic neighborhoods as reported by the Basij, among many similar schemes to intensify religious vigilance and oversight, as fewer and fewer Iranians observe religious norms.

The proposed budget attempts to present a picture of a leaner government with modest raises for agencies and ministries that are typically more transparent, while increasing disproportionately the resources of entities closely tied to opaque power centers. A tweet by Pedram Soltani, the former vice president of the Chamber of Commerce, says it well: “The 1401 budget in one sentence: we tax you, and give the money to those who brought us to power.”

Does the proposed budget signal a danger the system senses to its existence and legitimacy, that discontent and protests could become even more widespread? Or, is the regime nervous about an uncertain succession, or possibly contested transition, when Ayatollah Khamenei dies? Is it placing its bets on loyal pillars that have a vested interest in keeping the regime intact? Time will tell.

From “Dutch disease” to “Iranian malaise”

In general, Iranian administrations have done a poor job of maintaining fiscal discipline. Budgets have run out shortly after mid-year, forcing the government to fill the gap by borrowing from the Central Bank and issuing debt. Financing the deficit by resorting to the Central Bank fueled inflation, and the debt financing crowded out resources that could have been made available to the private sector, which could have used such funds for investments and job creation.

The Raisi budget foresees a 19 percent deficit compared to 67 percent in the last Rouhani budget, which will be partially covered by the issuance of government debt. Internal observers were confused whether the proposed budget was inflationary or deflationary. If inflationary, the government won’t meet its deficit targets. If deflationary, Raisi is unlikely to generate the one million jobs per year he promised, the one million houses per year he vowed to build and reduce the poverty he hopes to eradicate.

In some ways, sanctions have helped address a long-time curse: reliance on oil. The economy has diversified substantially to meet domestic demand. Moreover, as sanctions truncated oil earnings, the state depends increasingly on taxes to fund itself. Academic literature suggests that reliance on tax income forces governments to become more accountable and democratic since voters use the ballot box to get rid of ineffective officials. Yet, the Guardian Council predetermines election outcomes and neutralizes the ability of citizens to demand accountability.

Scholars also often state that Iran’s economy suffers from the “Dutch disease,” which is a situation when natural resource exports overvalue the country’s exchange rate. This makes the exports of goods and services uncompetitive. But with uncertain oil revenues and the depreciating rial, exporters of the increasingly diversified range of products cannot benefit from exchange rate advantages as sanctions curtail their access to markets. Thus, Iran no longer suffers from Dutch disease.

Conclusion

The Supreme Leader’s recognition of the country’s economic performance was long overdue, and it was most likely intended to point fingers at the former President Rouhani’s administration and deflect criticisms from himself and his handpicked President Raisi. It would, therefore, not have been unreasonable to expect that the Raisi government would have been better prepared with policies, star performers, and shovel-ready programs to hit the ground running. After all, ever since Rouhani’s re-election victory against Raisi in 2017, it was widely suspected that the regime would engineer Raisi to be the next president. Instead, the quality of his team and the dearth of ideas is perplexing. Even the hardline parliament couldn’t help but complain numerous times that the president surrounds himself with a better team. Raisi, in turn, has asked for patience and reiterated that his policies would bear fruit in the next few months, even if he has resorted to some unusual methods, such as prescribing that inflation be lowered, or asking the Qom Seminary to provide solutions.

Sanctions have been a useful excuse for the underperformance of the economy and the institutions that underpin it. They bear part of the blame, but not all. The competition for power between the so-called reformists and hardliners resulted in gridlock. Unity was the rationale for bringing all branches under ultra-hardline control, even at the cost of alienating the population and erstwhile brethren. Historians will be quick to remind us that the beginning of the end of the Shah’s reign was when he established a one-party system—the Rastakhiz party—ostensibly to unify resolve and speed things up. Has the Islamic Republic now done the same?

On the eve of the forty-third anniversary of the Islamic Revolution on February 11, a second phase is underway, one that builds on far shakier grounds than the first one, which inherited substantially more robust economic fundamentals and still failed to deliver on any of its economic promises. Even with all branches of the regime now in the hands of hardliners, it’s unlikely that the Raisi government can turn Iran’s economic ship around by undertaking the much-needed reforms that could unleash Iran’s immense economic potential. At the very least, he could avoid making things worse.

Nadereh Chamlou is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and was formerly a senior advisor to the chief economist at the World Bank’s MENA Region. Follow her on Twitter: @nchamlou.

Further reading

Fri, Jun 26, 2020

Just how happy are Iranians with their lives?

IranSource By

Iran ranks 118 out of 153 countries on the UN’s 2020 World Happiness Index (WHI), slightly above the lowest quintile—the least happy.

Fri, Feb 1, 2019

Iran’s economic performance since the 1979 Revolution

IranSource By

Forty years have passed since the Iranian Revolution—a revolution that promised to usher in democracy, freedom, and prosperity for all. Ayatollah Mohammad Yazdi, an influential cleric, recently exclaimed that Iran has progressed more in the last “forty years than it had in the 400 years prior.” Has it? This note offers some perspectives on selected economic […]

Tue, Mar 9, 2021

As Iran enters a new century, many old challenges remain

IranSource By Nadereh Chamlou

At the dawn of their new century, Iranians still aspire for an accountable and effective government, social inclusion and economic security, and a productive and respectful collaboration with foreign powers.

Image: A man sleeps by his motorcycle in Tehran, Iran August 24, 2015. REUTERS/Darren Staples