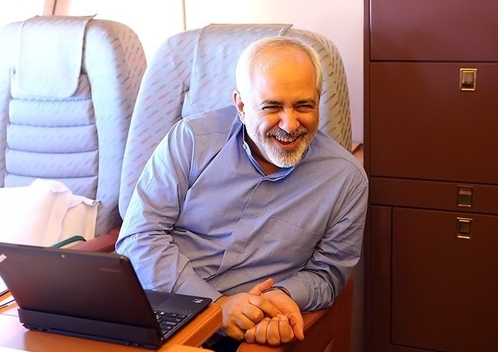

Iran’s US-educated Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif has always had enemies within the Iranian establishment.

Iran’s US-educated Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif has always had enemies within the Iranian establishment.

When Iranian-Canadian journalist Maziar Bahari was imprisoned during the 2009 post-election protests known as the Green Movement, his interrogators demanded not only that he admit to being a CIA agent but that Zarif—who had been sidelined by then hardline President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad after serving as Iran’s UN ambassador—had ties “to Western intelligence agencies.” By formally accusing Zarif of espionage, hardliners could have ended his career once and for all.

Zarif experienced a comeback after Hassan Rouhani’s election as president in 2013. Since his appointment as foreign minister in August 2013, Zarif has come under relentless attack from hardliners for pushing rapprochement with the West and negotiating the 2015 nuclear agreement known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Being called a Western spy or traitor is thus nothing new for Iran’s top diplomat.

Scrutiny of the “smiling minister” intensified once US President Donald Trump decided to withdrawal from the JCPOA in May. Hardliners have always argued that the Rouhani administration should never trust the United States, and Trump pulling out confirmed their stance.

With the re-imposition of unilateral and secondary sanctions after the US pullout, the Rouhani administration has had to address a variety of issues that impact the Iranian economy, including demands by the Paris-based Financial Action Task Force (FATF) that Iran address insufficiencies in its anti-money laundering and countering terrorism-financing measures.

Rouhani proposed several bills to prevent Iran from being blacklisted by FATF, which monitors the integrity of the international financial system. Tehran had failed to implement nine out of ten guidelines, and was given several extensions to pass the necessary legislation and bring Iran’s financial sector in line with international norms.

One of the main bills prompted a major debate within the Iranian establishment with even Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei criticizing the bill, only to accept it later, realizing it would help the country’s standing. Hardliners vehemently opposed the bill fearing that if they gave in, Iran would be controlled by the West and no longer able to fund proxies and militant groups such Lebanese Hezbollah. The bill eventually made it past parliament only to be turned down by the Guardian Council, on the basis of “flaws and ambiguities.”

The Rouhani administration believes the FATF bill is integral to keep Iran’s economy afloat after the US withdrawal and re-imposition of sanctions. In an interview with Khabar Online on November 10, Zarif spoke of money laundering as a “reality” and said that “there are many who benefit” without naming specific individuals or entities, though it’s assumed he was referring to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and organizations affiliated with the Supreme Leader. Zarif claimed that these groups made billions of dollars from money laundering and wanted to prevent the FATF bill from passing.

The foreign minister’s comment prompted widespread outrage amongst hardliners and even a summoning by parliament’s National Security and Foreign Policy Commission on November 11. Zarif defended himself, arguing that he had not specifically accused any Iranian institution of money laundering.

Hardliner MP Javad Karimi-Ghodousi, who has gone after Zarif in the past, called the foreign minister “the root cause of most of the woes Iran is currently facing.” Karimi-Ghodousi added, “By accusing other institutions, [Zarif] is trying to evade responsibility for the problems he created,” and called for the impeachment of “this paper tiger.” The spokesman of the judiciary demanded the foreign minister provide evidence to support his claims, while Judiciary Chief Ayatollah Sadeq Larijani weighed-in on November 19, calling Zarif’s comment a “stab right into the heart” of the Islamic Republic.

By then, rumors had begun circulating that the Iranian foreign minister had resigned, the second time such reports have surfaced since October. The foreign ministry spokesman Bahram Ghasemi eventually spoke out: “For sure, I reject this rumor. These are deliberately manufactured, processed and spread by certain circles. Mr. Zarif is energetically busy with his work. He was in parliament yesterday and today he is hosting a foreign delegation.”

Since the controversy began, many in Zarif’s circle have come to his defense, even going as far as disclosing “dirty money” numbers to buttress the foreign minister’s claims. Despite this, two dozen members of parliament submitted a proposal to impeach Zarif this past week. If he is removed, he would be the third minister impeached in recent months.

Aside from his “improper position on money laundering,” Zarif is accused of “failing to ensure national interests in international agreements,” “neglecting the economy in the country’s diplomacy,” “endangering the defense potential of the country,” “neglecting the expansion of ties with Asian, African and Latin American countries,” and appointing “inefficient ambassadors.” The proposal, which contains a total of eleven accusations, has garnered twenty-four signatures, enough to allow the procedures to move forward.

Etemad, a reformist newspaper that supports Zarif, claimed that members of parliament have an “addiction to impeachment” and accused them of abusing their authority by impeaching ministers at the “wrong time.” Javan, a conservative newspaper known for criticizing the foreign minister, also spoke out in support of him in an editorial with the headline, “Abort the Zarif impeachment” and also called parliament’s timing wrong. Similarly, on November 28, Ayatollah Naser Makarem Shirazi, a hardline cleric, defended Zarif saying, “If we want to change any ministers, especially ministers who are facing the enemy, it would the wrong move and the government should not be weakened in the current situation.”

It’s clear that hardliners are working to scapegoat the Rouhani administration for all of Iran’s economic woes, which includes rampant corruption and mismanagement. When a hardline MP was unable to gain traction to impeach the Iranian president earlier this year over nationwide protests and the state of the economy, they went for his ministers instead. In August, parliament impeached the minister of economic affairs and finance over the deterioration of the Iranian economy and the drop in the rial. Impeaching a foreign minister merely for speaking the truth about Iran’s endemic corruption and for negotiating a multilateral agreement—which the US, not Iran, violated—is not a justifiable offense.

Hardliners are merely looking to punish Zarif for negotiating the JCPOA in the first place—and to wipe that smile permanently off his face. However, Zarif is believed to retain the support of Khamenei and is likely to have the last laugh, for now.

Holly Dagres is editor of the Atlantic Council’s IranSource blog, and a nonresident fellow with the Middle East Security Initiative in the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security. She also curates The Iranist newsletter. Follow her on Twitter: @hdagres.

Image: Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif leaving Tehran to Vienna on April 6, 2015 (Mohammad Hassanzadeh)