Japan’s energy policy towards Iran has been an area of struggle for independence from the United States for four decades.

Japan’s energy policy towards Iran has been an area of struggle for independence from the United States for four decades.

Even when Japan tried to pursue its own energy policy towards Iran, the US has generally had the final say. From Japan’s point of view, however, the US stance towards Japan-Iran energy relations has toughened gradually since the 1979 revolution.

In the early eighties, for example, Washington was not completely against Tokyo’s close relations with Tehran. At the end of 1980, even while Iran held US diplomats hostage, Japan kept importing Iranian oil. Japan continued these imports, as did some European nations, disregarding US warnings that the oil revenue would help Tehran’s war effort against Baghdad during the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq War. (According to the memoir of Shigeo Muraoka, a retired Japanese trade official, then UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher declined President-elect Ronald Reagan’s request to persuade oil companies to stop buying oil from Iran, saying “it is beyond my reach.”)

These days, however, the US has made it much more difficult for Japan to keep importing sizeable quantities of oil from Iran. Japan imports almost all its oil and historically, Iran has been an important and stable supplier. There is a famous episode in 1953, when Iran was under a British blockade for nationalizing Iranian oil. Japan began to directly import oil from Iran, ignoring the British blockade, which marked the beginning of Japan’s direct import from oil producing countries. Japan had relied in the past on “oil majors” for its supplies, which was very expensive. The import of Iranian oil was welcomed in Japan, in the context of regaining confidence in the post-WWII reconstruction period.

Even today, no Japanese official would question the importance of Iranian oil for Japan. When oil imports from Iran became difficult in 2012, due to multilateral sanctions against Iran over its expanding nuclear program, the Japanese government established a sovereign insurance scheme to facilitate continued imports. The scheme was introduced just before European re-insurance companies stopped covering tankers carrying Iranian oil. This special sovereign shipping insurance is still in effect.

However, it is necessary to establish a payment mechanism for Iranian oil to avoid US sanctions, which were re-imposed last November. The “toughest ever” US sanctions against Iran target all financial institutions that are involved in any kind of dealing with Iranian oil and it is impossible for foreign financial institutions to be part of a payment mechanism without a solid guarantee from the US that they will not face fines or exclusion from the US market.

Even though the US has issued waivers for eight countries to keep importing Iranian oil until March, for Japan, resuming oil imports from Iran has remained a difficult task, though it is vital for maintaining diversity of source of oil for Japan’s energy security. Japan imported close to 560,000 bpd from Iran in 2005 but cut the amount gradually and then significantly in 2012. In 2016, after the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), it increased again but in 2017 it declined to 165,000 bpd. The figure for October 2018, was about 50,000 bpd. It is not clear when and how much Japan will resume to import.

US sanctions have also jeopardized Japanese investment in Iran’s energy sector. In 2004, Japan signed a contract to develop Iran’s giant Azadegan oil field, despite US opposition. Japan eventually pulled out of the contract in 2010, after significantly reducing its share from 75 percent to 10 percent in 2006. This occurred after the Iran nuclear issue was referred to the UN Security Council. The Azadegan oil field was divided in two and one of them, the North Azadegan oil field, is now being developed by the China National Petroleum Corporation.

The possibility of re-entering Azadegan emerged after the implementation of the JCPOA in January 2016. However, that opportunity has been dashed again with the US unilateral withdrawal from the JCPOA last May. Japan still supports the nuclear deal as an international agreement in line with the Non-Proliferation Treaty, which was also endorsed by the UN Security Council. Like many US European allies, Japan had hoped that the JCPOA would be an important step for peace and stability in the Persian Gulf region. More than 80 percent of Japan’s oil comes from this region and thus is of vital importance for Japan’s economy.

With the Trump administration’s apparent determination to “punish” Iran for its non-nuclear activities, Japan’s desire for stable energy relations with Iran is again threatened. Iran has never been seen in Japan as a security threat. On the other hand, the turbulent East Asian security situation—and Japan’s reliance on US protection and its nuclear umbrella—does not leave much room for Japan to act too independently on Iran. Even though Japan wants to preserve the JCPOA, it cannot afford to antagonize the US administration considering the current unstable security environment.

Nevertheless, Japan will still try its best to save the JCPOA for it also fears that the collapse of the agreement would exacerbate instability in the Persian Gulf region. Thus Japan is trying to establish a mechanism to pay for Iranian oil without violating US sanctions.

With European countries still struggling to establish a Special Payment Vehicle to continue limited trade with Iran, it will no doubt be far from easy for Japan to create a similar mechanism. However, just increasing pressure to “make Iran surrender” with no end-game in sight will be detrimental to the stability of the region, which clearly goes against Japan’s national interests to secure a stable energy supply. Japan’s quest for independence in its energy policy thus continues.

Sachi Sakanashi is a senior research fellow at the JIME Center, Institute of Energy Economics, Japan (IEEJ).

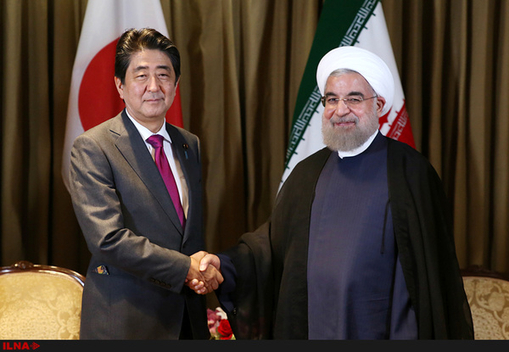

Image: Japanese Prime Minister Shinzō Abe and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani on the sidelines of the 2016 United Nations General Assembly (ILNA)