Though August 6 marked the first set of re-imposed US sanctions against Iran, the economy had already started feeling the pain months earlier. Uncertainty about the future stirred up turbulence in the Iranian foreign exchange, and caused scarcity as well as a sharp price increase of essential goods, in addition to the gradual withdrawal of foreign companies investing in the country.

Though August 6 marked the first set of re-imposed US sanctions against Iran, the economy had already started feeling the pain months earlier. Uncertainty about the future stirred up turbulence in the Iranian foreign exchange, and caused scarcity as well as a sharp price increase of essential goods, in addition to the gradual withdrawal of foreign companies investing in the country.

Meanwhile, there have been reports of some businesses misbehaving: such as in-store hoarding, non-oil exporters refusing to supply export proceeds to the market, and Iranians rushing to shops due to worries over further price hikes.

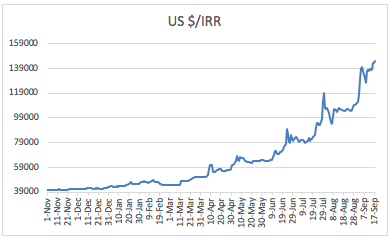

The national currency, the rial, was the first market that reacted to the threat of unilateral sanctions. Since November 2017, the rial started to plummet. The value of the rial against the US dollar has dropped by more than 250 percent since November, from 40,530 to 160,000 on September 24.

First and foremost, the rial depreciation is reflected in the inflation rate, mainly through the rise in costs of inputs and also through the economic anxieties it triggers. It is likely that in the second half of the current Iranian year (March 2018 – March 2019)—as a result of continued rial slide and shrinking domestic production—the economy will start struggling with double-digit inflation, after being in a single-digit realm for almost two years since the signing of the 2015 nuclear agreement.

Some experts maintain a positive outlook, claiming a very sharp increase in the inflation rate during the second half of the year is unlikely because of the inflow of petrodollars and market control mechanisms pursued by the Iranian government, not to mention their ability to evade sanctions.

Still, sanctions are expected to have a negative impact on GDP through a decline in oil exports, transport, industrial, service, and construction sectors. In its latest report, the Economist Intelligence Unit estimated a GDP growth rate of 1.6 percent for 2018, down from 3.8 percent in 2017. Meanwhile, the Central Bank of Iran’s first quarterly report of the year shows the economy grew by 1.8 percent last spring, which is 2.8 percent lower than last year.

The situation is expected to get worse in the last quarter of the year as the effect of oil exports drop will also be reflected in the GDP. According to Mohammad-Bagher Nobakht, the head of Iran’s Management and Planning Organization, the country exported 2.457 million bpd of oil from April to August 2018, up 10,000 bpd from the initial budget projection. But in September, Nobakht said that Iran’s oil exports dropped to 1.118 million bpd, and that the Iranian government has initiated strategies based on three scenarios of oil export drops:1.7 million bpd, 1.5 million bpd, and 1 million bpd.

On the up is trade with Russia and Oman, two countries Tehran has warm and expanding political ties. Statistics released by Iran’s Customs Administration (IRICA) show imports from Oman has increased by 318 percent during the first five months of the Iranian year, while Russian imports have soared by 116 percent. But a change in the country’s major trade partners—currently China, India, South Korea, Turkey, and the U.A.E.—is highly probable due to money transfer problems.

Iran will have to resort to an oil-for-goods arrangement which means more trade with oil buyers. In March, on the sidelines of the fourteenth Joint Economic Cooperation Commission, Tehran and Moscow agreed, among other things, on cooperation in oil and gas swap deals.

Although the Iranian economy is in decline due to a number of factors—sanctions, corruption, and mismanagement—it is certainly not collapsing. Oil exports will decline but not to zero, which the Trump administration is aiming for. The inflation rate will increase but not on the path of hyperinflation. The GDP will decline but still not as low as it was in 2012, when the economy contracted by 6.8 percent.

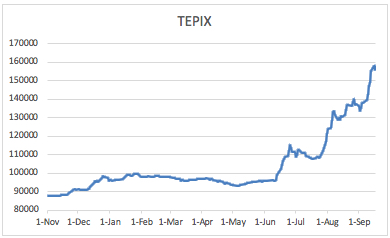

Moreover, the main index of the Tehran Stock Exchange (TEPIX) has shown little reaction to the intensified external pressures, and has increased by 79 percent in ten months. During all the years of multilateral sanctions before the signing of Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, the TEPIX has been growing because of the positive effect of the plummeting rial on the profitability of export-oriented companies.

Without a doubt, the uncertainty caused by sanctions have inflicted substantial costs on the Iranian economy but this should not distract from other causes. Some observers believe that sanctions have worked as a catalyst since the economy is also suffering from a set of self-inflicted problems including: runaway liquidity, an obscure business environment, mounting government’s debts, corruption, an outmoded banking system, and a politicized environment for making economic decisions.

The $20.6 million (18 million euros) economic package the European Union is preparing for Iran is able to act as a remedy through securing financial channels for transferring oil export money and establishing partnership between small and medium-sized enterprises. But it will not be able to provide the investment Iran needs to create millions of jobs. As a result, Tehran is trying to further solidify relations with China and Russia.

In July, the Supreme Leader’s Foreign Affairs Adviser Ali-Akbar Velayati visited Moscow to deliver Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s message to Russian President Vladimir Putin. Velayati called the negotiations very “constructive” and underscored that Khamenei considered bilateral relations “strategic.” In a separate development, the head of the Iranian Council of Foreign Affairs Kamal Kharrazi visited Beijing in September during which he unveiled a package proposed by Iran for engagement in China’s expanding road and rail networks including the Silk Road project.

From the Iranian leadership’s vantage point, a main difference between the 2012 and 2018 sanctions is that new sanctions are imposed by the US unilaterally, and European initiatives can help Tehran to continue selling oil and use a channel for money transfer. However, Tehran is facing some new challenges.

Today, most of Iran’s allies implement the anti-money-laundering regulations, which makes money transactions more difficult for Iran since it has not yet been removed from the Financial Action Task Force’s (FATF) blacklist. Tehran is currently considering FATF legislation.

Similarly, the bitter experience of the 2012-sanctions busting measures, which brought opaqueness and developed domestic corrupt networks, makes the path forward more difficult for the Rouhani administration. The disclosure of rampant corruption and cronyism in recent years, associated with the senior leadership of the Islamic Republic, has undermined the Iranian people’s trust in the establishment. Bearing the pain of sanctions has become difficult for people who see the luxurious lives of senior officials’ relatives.

It is also important to bring social factors into consideration. In his book, The Status of Human Development in Iran, sociologist and former political prisoner Saeed Madani argued that “although Iran is one of the most secure regional countries, the current economic, social and political crises and the ruling establishment’s reluctance to meet people’s demands for change on one side, and the presence of regional paramilitary groups on the other, escalates risk of future tensions.”

On this basis, some observers believe that because of the existing underdeveloped conditions in different Iranian provinces, compounded with deteriorating economic conditions, the resumption of economic-driven protests that erupted in December 2017 are likely.

Hoorozan is the pen name of an energy and economics analyst based in Iran. Follow her on Twitter: @HooRozan.

Image: An Iranian man taking note of the exchange rates (Jam-e Jam)