Will Haider al-Abadi survive Iraqi politics? The new Iraqi prime minister has certainly made bold decisions early on into his tenure as prime minister. Nevertheless, his political survival remains an uncertainty. Despite the years-long threat posed by the Islamic State (ISIS or ISIL), the real danger to his authority lies in Iraq’s politics. The layers of conflicting interests and disputes that have been built up over the past decade, are considerable, to say the least. But for Abadi to lessen his vulnerability, along with the high degree of uncertainty that plagues his position, he may be forced to follow the footsteps of his predecessor, Nouri al-Maliki, and consolidate power.

Will Haider al-Abadi survive Iraqi politics? The new Iraqi prime minister has certainly made bold decisions early on into his tenure as prime minister. Nevertheless, his political survival remains an uncertainty. Despite the years-long threat posed by the Islamic State (ISIS or ISIL), the real danger to his authority lies in Iraq’s politics. The layers of conflicting interests and disputes that have been built up over the past decade, are considerable, to say the least. But for Abadi to lessen his vulnerability, along with the high degree of uncertainty that plagues his position, he may be forced to follow the footsteps of his predecessor, Nouri al-Maliki, and consolidate power.

In Washington, the conventional narrative is that Abadi is the anti-Maliki—committed to stamping out corruption, nepotism, and incompetence within Iraq’s security institutions, redirect its strategic orientation closer to the United States, rectify Baghdad’s relations with the Arab world, and reconcile and reintegrate Sunni and Kurdish factions into an inclusive, power-sharing government.

In many ways, Abadi’s rhetoric and actions reflect the West’s hopeful expectations. Over the past month, Abadi sacked fifty senior officers and officials from Iraq’s military and security institutions—including Adnan al-Asadi, the acting minister of interior. Earlier this month, he announced that Iraq allegedly paid 50,000 “ghost” soldiers from its budgetary payroll, and made it his goal to challenge those actors benefiting from a corrupt and broken system. “There are a number of ‘ghost soldiers’ in other ministries. I am moving forward with reform to expose them,” Abadi stated. “Campaigns were launched and others will be launched to topple me… However, I will not back off, even if [this] leads to my assassination.” He clearly expects the resulting battles and threats as he aims to push for systemic reforms that cut against the grain of Iraq’s politics.

But while Abadi presents a willingness to combat corruption, incompetence, and sectarianism, the flip side is that these actions follow the same path toward consolidating power and securing his position from current and potential threats against his authority. Purges within the security forces were inevitable, but more importantly, have less to do with fighting corruption itself. Despite Abadi and Maliki coming from the same Shia Islamist party, the new Iraqi leader was unlikely to allow the security architecture that his predecessor built to remain intact. To do so would undermine his position and jeopardize his political survival.

In addition, Abadi has openly pleaded for increased security assistance from the United States, in the form of more airstrikes against Islamic State militants and more military resources supplied to Baghdad. While Washington may view the prime minister’s calls for more Western military engagement as a desire to see greater American influence, one should not interpret it as a willingness to reorient Iraq’s strategic orientation closer to the United States. For Abadi, the defeat of the Sunni insurgency is not a goal in of itself, but a means to regime building. Abadi surely desires intensified US engagement, perhaps on all fronts, but the underlying rationale is driven by concerns over his own political survival. Indeed, just as the US military’s presence served to build and secure Maliki’s Iraq, the current prime minister hopes to piggyback off the growing US presence and influx of resources to help him fortify and deepen his staying power, thus reducing his level of dependency.

Some Sunni Arab political elites are beginning to see Abadi as an ineffective leader and someone too weak to deliver on his promises. “Just talk,” one senior Sunni Arab politician described the new prime minister. “He makes promises to us like Maliki did, but nothing happens.” The lack of movement in drafting and ratifying a law that erects a Regional National Guard—a force made up of local Sunni Arab tribal fighters to combat the Islamic State in Sunni-dominated territories—is one of many political issues that Abadi must balance between revisionist and status quo advocates, often times marked by sectarian fault lines.

Recently, Abadi’s weakness was on full display as Iraq’s judiciary delivered death sentences to Sunni Arab elites arrested by the government in accordance with Article IV of the counterterrorism law. The court condemned former member of parliament Ahmed al-Alwani to death, a man whose release remains a Sunni political demand —along with the repeal or reform of the counterterrorism law, which many Sunnis claim has been politicized by the government and selectively used to marginalize them. The judiciary remains highly influenced by the Maliki era. “Iraq’s judiciary is still handing down convictions in politicized trials, fraught with legal irregularities,” said Joe Stork, deputy director of Middle East and North Africa at Human Rights Watch. “Despite promises of reform, the government is sitting idly by while Iraq’s terribly flawed justice system sentences people to death on little or no evidence.”

While it is too early to tell, Abadi’s path to securing his position may come in the form of masking his consolidation of power through the process of pushing and implementing reforms that increases his control and builds a regime loyal to him. On one hand, Abadi’s dilemma is characterized by his practical weakness; on the other, it is shaped by his political vulnerability. To satisfy Sunni and Kurdish demands, the prime minister needs to make compromises to devolve Baghdad’s power. But he is not powerful enough to make such concessions. While the West hopes that Abadi shapes Iraq, it may be the case, that over time, Iraq will shape Abadi. To be certain, the same structural and systemic features that have characterized post-Saddam Iraq remain intact. The constraints that undermine compromise and the incentives to maximize power have not followed Maliki’s exit. They remain forces that Abadi recognizes and must deal with, especially if he wishes to survive in Iraq’s jarring politics.

Ramzy Mardini is a nonresident fellow at the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

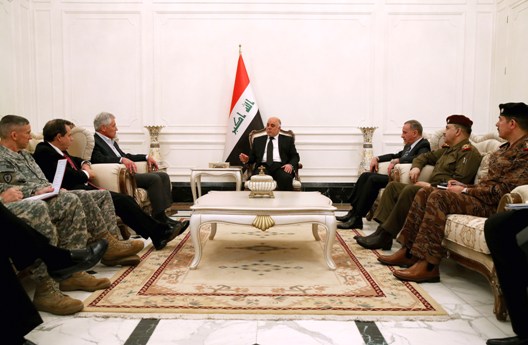

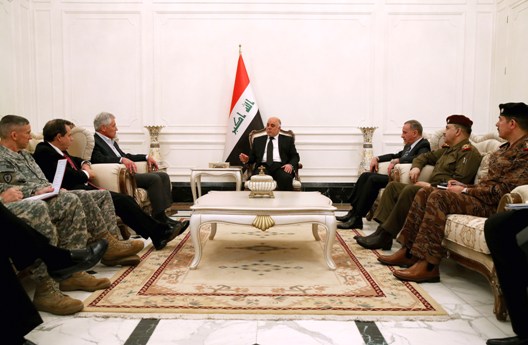

Image: U.S. Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel (3rd L) meets with Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi (C) in Baghdad December 9, 2014. REUTERS/Mark Wilson/Pool