Ammonium nitrate didn’t belong to Hezbollah, but they knew about its dangers

Beirut is still reeling from the August 4 explosion at its seaport—an event that’s being described as one of the largest ever non-nuclear explosions in the world and the worst disaster in Lebanon’s tragically violent history. As the Lebanese capital tends to its wounds, officials are investigating and promising to hold those responsible accountable. But citizens are understandably loathe to trust the same ruling clique whose incompetence and negligence caused this tragedy. Trending Arabic hashtags like #Prepare_the_Gallows capture their anger, which is generally directed towards Lebanese officialdom rather than just a single party or group. Some, however, are pointing their accusatory finger squarely at the militant group Hezbollah. Despite indications that the Party of God may not have been directly responsible for the incident, the group should not escape scrutiny.

Suspicions that the stash of 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate belonged to Hezbollah aren’t entirely unfounded. The group is known to exercise a degree of control over Beirut’s port and has a history of stockpiling and using the material in several of its global operations, including in London, Berlin, Thailand, Cyprus, Bulgaria, and elsewhere. But determining Hezbollah’s guilt based on its control over Beirut’s Port is relying circumstantial evidence, at best. Moreover, the group’s prior use of ammonium nitrate isn’t necessarily probative of its ownership of the cache at Beirut Port.

In fact, it seems responsibility for the explosive cache might never be definitively determined. The Lebanese government’s track record of bad faith investigations—and the fact that the game of “hot-potato” for responsibility has already begun—suggests its ongoing investigation into the matter might result in little more than a show trial scapegoating low–level bureaucrats to cover for more powerful officials.

The information currently available suggests that Hezbollah may not have been responsible for the importation of the ammonium nitrate nor its storage at Beirut Port. In 2013, Lebanese authorities seized the explosive material from aboard the Rhosus, a Moldovan-flagged ship captained by a Russian national, en route from Georgia to Mozambique. The cargo was then stored at a Beirut Port warehouse. There, due to the Lebanese authorities’ hallmark traits of incompetence and negligence, this ticking timebomb lay dormant—with several Lebanese officials having full knowledge of the risk involved—until some hapless welders accidentally set it off on August 4. Casting further doubt on Hezbollah’s ownership of the cache, explosives expert Dr. Rachel Lance said that the reddish color of the debris and smoke cloud from the explosion indicates that the ammonium nitrate—destructive as it was—was not military grade.

Nevertheless, Hezbollah shouldn’t be absolved of responsibility for the incident, as it hardly seems plausible that the group was unaware of the presence of the deadly cargo in the port’s warehouse, despite Nasrallah’s public denial to the contrary. According to the Treasury Department, Hezbollah’s security chief security Wafiq Safa exerts considerable influence over the activities at Beirut’s Port. Moreover, in addition to its connections to the Lebanese intelligence community, the group boasts its own vast and powerful intelligence apparatus that has previously demonstrated acute awareness of occurrences in Lebanon. Hezbollah simply couldn’t have missed the presence of this publicly known—albeit neglected—stash of chemicals.

The group is also acutely aware of the danger that such chemicals—even if not of a military grade—pose to nearby civilians, perhaps more so than any other entity in Lebanon. In fact, they factored it into their military deterrence calculus vis-à-vis the Israelis.

Beginning in February 2016, the group’s Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah threatened to inflict an explosion similar to Beirut’s upon Israel by targeting the latter’s ammonia tanks in Haifa. “Lebanon today possesses a nuclear bomb. I’m not exaggerating at all. A few of our missiles [fired at] these ammonia tanks in Haifa would produce a result similar to a nuclear bomb,” Nasrallah said at the time, repeating permutations of that threat several times in subsequent years.

Furthermore, as Lebanon’s strongest faction—possessing its own shadow state, media organs, influential parliamentary bloc, and ministerial presence—Hezbollah may have been uniquely positioned to rectify this dangerous oversight. And yet it failed to do so.

The group has long been a critical political player in parliament (since 1992) and the cabinet (since 2005) and has formed crucial alliances to amplify its governmental numbers. Hezbollah has used the latter to either promote its interests or otherwise obstruct Lebanon’s political process until it gets its way. Yet at no point did the group use this outsized influence to raise the issue of the ammonium nitrate stored in Beirut’s port. This was the case despite the fact that, at almost all times during the relevant time period between 2013 and the August 4 explosion, Hezbollah’s allies headed the Transportation Ministry responsible for all Lebanese ports, including Beirut’s, and the Finance Ministry, which controls the Lebanese Customs Authority.

Nor did Hezbollah try to remedy this oversight or raise public concern about it through its vast private resources, which it has not hesitated to mobilize in the past when need for it arose. Most conspicuously over the past decade, it enthusiastically deployed its forces to Syria at Iran’s behest to rescue Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s regime, notwithstanding the vast price Hezbollah paid in blood, treasure, and prestige, and the negative repercussions this intervention had on Lebanon.

Hezbollah has also unilaterally acted within Lebanon in the past when it has felt justified in doing so. The group has been traditionally cautious about appearing to take over the Lebanese government’s prerogatives, even as it quietly usurps them. For example, through its motto of “Army, People, Resistance,” Hezbollah seeks to convey the impression that its armed activities complement, rather than replace, those of the Lebanese Armed Forces. Yet, in 2017, the group disposed of this caution when its black-clad militiamen conducted a unilateral police-raid against drug-dealers and gangs in south Beirut’s neighborhood of Burj al-Barajneh. Hezbollah executed the operation to address a public safety concern that they claimed the state’s official security forces were incapable of solving.

Later that same year, Hezbollah brought the full weight of its massive apparatus to bear on destitute Shia shopkeepers in Hay al-Sullom, a neighborhood in its southern Beirut stronghold. The shopkeepers attacked Hezbollah on national television for inspiring a slum clearance and redevelopment project that deprived them of their meager livelihoods—admittedly derived from illegal kiosks. But because this criticism threatened Hezbollah’s carefully-crafted image as the caretaker of the traditionally downtrodden Shia community—the very source of its strength and legitimacy—it spared no effort to cow them into silence, including defamation via traditional and social media, armed and verbal intimidation, and exploitation of the Lebanese legal system.

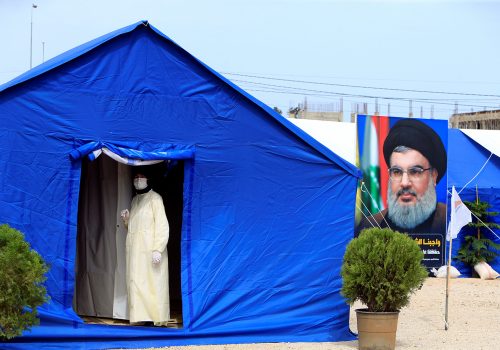

The group didn’t have to go to such extremes if it wished to privately address the issue of the stored ammonium nitrate. It could have employed its media organs—or Nasrallah’s oft-used bully pulpit—to raise awareness of the danger lurking at Beirut’s port, as it has been doing with COVID-19 to bolster its aura of social responsibility since the outbreak spread to Lebanon.

Hezbollah presents itself as being cut from a different cloth than other Lebanese political factions, such as being incorruptible and uniquely concerned for Lebanon’s security, dignity, and sovereignty. That’s how it justifies its retention of a vast private arsenal. Its utter failure to even raise the matter of the 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate—a bomb in the heart of Beirut—conclusively demonstrates the falsehood of its claims. It reveals Hezbollah as yet another corrupt faction benefiting from, and therefore feeding into, Lebanon’s nepotistic system, whose corruption and incompetence led to the explosion on August 4. Nasrallah often likes to state that “Hezbollah will be present wherever we must be present.” But where were they when Lebanon needed them this time? Most likely occupied with the continued obstruction of critical reforms that could have averted this disaster to serve its own interests.

David Daoud is a research analyst at United Against Nuclear Iran (UANI) on Hezbollah and Lebanon. Follow him on Twitter: @DavidADaoud.

Image: Lebanese army members walk near the damaged grain silo at the site of Tuesday's blast, at Beirut's port area, Lebanon, August 7, 2020. REUTERS/Mohamed Azakir