Black Iraqis have been invisible for a long time. Their vibrant culture and struggle must be recognized.

When roaming the streets of Hila or Baghdad, it is almost impossible to tell who is Sunni, Kurdish, Baha’i, or Mandaean. One community, however, stands out in the intricate cultural, religious, and ethnic mosaic of Iraq due to its largely visible ethnic origins: Black Iraqis. Concentrated in the outskirts of Basra and Zubair in southern Iraq, this community is linked to a dark historical era when Basra was once a prominent center for the slave trade in the Islamic Empire between the ninth and nineteenth centuries. Visible traces of structural racism and xenophobia persist today and can easily be identified in the power relations governing Black Iraqis and the rest of society.

Black Iraqis are not only living on the geographical margins of urban agglomerations but also on the margins of society and its structures, with no political representation, no tribal umbrella, locked social mobility, and the constant stigma of being called abd (“slaves”), fahma (“piece of coal”), or other ethnophaulisms in everyday interactions. The community witnessed a short-lived political revival following the 2008 election of Barack Obama as the first black president of the United States and, more recently, with the Black Lives Matter movement, as media articles rushed to document this newly witnessed awakening. However, activists in Iraq calling for Black Iraqi rights continue to face violent oppression as members of the community and its activists have become targets of radical groups in recent years and have, unfortunately, opted to tone down their demands.

I was lucky enough—through an ethnographic project carried out with other Iraqi researchers—to penetrate the secretive world of Iraqis of African descent and discuss their positionality as a group in Iraq today and their unique Afro-Iraqi memory with local activists, performers, and academics from within the community, as well as with a few United Nations agencies. The observations and information I have included in this piece emanate directly from these fascinating first-hand encounters and debates.

Twelve centuries of disgrace

Black Iraqis are the descendants of immigrants and enslaved people from Sub-Saharan and East Africa. Their presence in Iraq dates back to the Abbasid empire, starting from the ninth century when some newcomers came to the region as sailors, workers, captured slaves, or enslaved soldiers. They largely originated from the coast of modern-day Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, Zanzibar, Ethiopia, and other African countries. In the absence of formal statistics, their community leaders estimate their numbers today to be as high as 1.5 to 2 million inhabitants. Black Iraqis are scattered across diverse regions of the country, concentrating in the governorates of Basra, Maysan, and Dhi Qar. There are also a few families in Baghdad, Wassit, and other cities. However, the largest community resides on the outskirts of the cities of Basra and Zubair.

Despite slavery being officially abolished in the nineteenth century and supported by Article 14 of the 2005 Iraqi Constitution, which stipulates “equality without racial-based discrimination,” Black Iraqis still endure systematic discrimination, marginalization, and structural racism embedded in historical stigmas and xenophobia against black people in the Arab world, according to activists I spoke to. Iraq is a melting pot of other ethnic, religious, and cultural communities. Yet, many of these groups are “invisible” and can easily fade in the crowd due to similar physical features. In contrast, Black Iraqis are the “visible others” who cannot be unseen or concealed. Hundreds of invisible cultural and social lines segregate the two communities, ostracize Black Iraqis, and reaffirm their otherness in urban design, tribal allegiances, and marriage arrangements.

One intriguing conversation I had with a group of non-black Iraqi academics, opened my eyes to the extent of denial most people feel about the subject. I was told repetitively, “We don’t have black and white in Iraq. We are all equal,” and was asked to drop the appellation black Iraqis or Afro-Iraqis and replace it with asmar or abu samra, which means tanned or brown in Arabic. Little did they know how offensive it is to deny the community its blackness and attempt to dilute it with a drop of whiteness. In contrast, the Black Iraqis I have been working with, including Dr. Thawra Yousif, Dr. Abdulkareem Aboud, and Dr. Abdel-Zahra Sami Farag, all influential figures in their community, proudly claim their blackness and celebrate it.

Structural racism and the absence of a tribal umbrella have relegated most black Iraqis to the margins of the economy and locked them into a number of small manual jobs as domestic help or performers. According to their representatives, the population also suffers from low educational attainment rates, unemployment, and poverty. Additionally, there is not a single Black Iraqi holding a high-ranking position in the government, nor do they have any political representation. Recently, human rights activists from the community have suffered assassination attempts and violence to oppress their demands, according to international reports.

A secretive African intangible heritage

Black Iraqis have maintained a vibrant cultural heritage, blending their Sub-Saharan and East African traditions and rituals with those of Mesopotamia. This distinctive intangible heritage has been dissolved or dissimulated sometimes for better integration and assimilation in the predominantly Arab and Islamic context of Iraq. Many aspects have survived and continue to flourish today. Black Iraqis possess a distinct dialect combining Swahili and Arabic, a particular genre of chanting, drumming, and tambourine performances, and continue to practice African-derived healing and exorcism ceremonies, which they practice secretly in remote huts called makkayid, away from the judgmental eyes of curious Arabs.

The body of literature documenting the diverse aspects of this culture remains sparse, as most studies solely focus on human rights concerns affecting the community rather than its ethnographic, cultural richness, avowal, and ascription of self and group. There are also few, if any, efforts to examine the stereotypes surrounding Black Iraqis through advocacy or education programs in an already highly contentious and fragmented social and political context, which widened the gap and emphasized disparities and stigmas regarding this community living in Iraq since the ninth century.

This dire economic and social situation contrasts with the community’s rich contribution to the cultural and artistic diversity of southern Iraq. Black Iraqi folklore and musical heritage have been transferred throughout the generations, maintaining original African names, such as the musical genres of bib, ankroka, gonbasa, al-liwa and the nuban, according to Dr. Abdelkarim Abdulkareem of the University of Basra and Abdel-Zahra Sami Farag. They also continue to use original drum and wind instruments with African ties like amsondo, kikanka, bato, and sarnai, while the performers hold mixed-gender dances dressed in vibrant embellished garments and animal skin belts. These traditional spectacles clearly set black Iraqis aside from the rest of the Iraqi gender-segregated society and are a strong staple of their African origins and identity. Abdel-Zahra Sami Farag, a local activist and performer, also revealed to me that members of the group regularly gather in the makkayid, where they perform folkloric and exorcism rituals.

Social cohesion is one of the main challenges facing Iraqi society today. Post-2003, many ethnic, cultural, and religious communities found themselves without state structures or a tribal umbrella that provides kinship support and protection that both Arabs and Kurds enjoy—both highly tribal societies. Black Iraqis are among these communities without tribal safeguards, legal status, or political representation. While other communities have received extensive media and academic attention after the invasion, Iraqis of African descent remain in the margins as an under-documented, under-studied, and highly visible “other” within.

Sarah Zaaimi is the deputy director for communications at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center & Middle East programs.

Further reading

Wed, Dec 14, 2022

Morocco’s World Cup victories are historical revenge for subaltern dreamers from the global south

MENASource By Sarah Zaaimi

The defeat-free journey of the Moroccan soccer national team, the Atlas Lions, is more than a simple sports score.

Mon, Mar 6, 2023

Afrocentrism is trending in the Maghreb. It’s because Sub-Saharan migrants are rewriting their narrative.

MENASource By Sarah Zaaimi

North Africa undoubtedly faces a serious migration problem that will continue to aggravate if not addressed regarding its social, cultural, and historical dimensions and root causes.

Mon, Jul 26, 2021

An “illiterate generation”—one of Iraq’s untold pandemic stories

MENASource By

The devastating impacts of COVID-19, coupled with years of spillover effects of violent conflict and extremism, have already proved to be detrimental to students whose education and future career ambitions already receive limited attention.

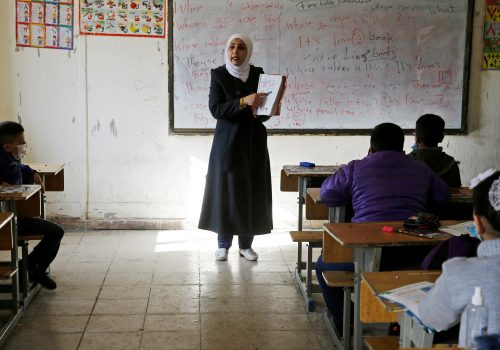

Image: African-Iraqi men sing after their group "Free Iraqi Movement" was approved as a political party to run in the coming local elections in Basra, 420 km (260 miles) southeast of Baghdad December 6, 2008. Inspired by Barack Obama's election in the United States, some black Iraqis plan to run in a forthcoming election, to end what they call centuries of discrimination because of their slave ancestry. Picture taken December 6. To match feature IRAQ/BLACKS REUTERS/Atef Hassan