The short answer is no, but the Tamarod or ‘Rebel’ campaign can certainly create a massive headache for President Mohammed Morsi, the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party, and the security apparatus. Tamarod campaigners have made an impressive splash on the Egyptian political scene in recent weeks, collecting signatures from ordinary citizens to demonstrate a vote of no-confidence against Morsi and demand early presidential elections under the supervision of the Supreme Constitutional Court.

First drawing attention in late April, the campaign’s stated goal aims to collect 15 million signatures before June 30. Tamarod was born out of the marriage of individuals from the Kefaya movement, one of the most significant pre-revolution grassroots organizations that broke the taboo against direct criticism of then-president Hosni Mubarak, and the Popular Current, the eclectic grassroots group of civil, leftist, Nasserist, and anti-Islamist advocates inspired by presidential candidate Hamdeen Sabbahi. Neither Kefaya nor the Popular Current claim the campaign as their own, but after initial hesitation over the stance towards its goals both organizations expressed support for the initiative.

As yet another demonstration of the strength of organized grassroots efforts within Egypt, and within only a few weeks of the start of the campaign, Tamarod claims it has gathered over three million signatures. And why not? Driven by the same youthful energy that galvanized and mobilized support for the January 25 revolution, the campaigners tapped into the sense of discontent that has gathered steam since the start of Morsi’s ascent to the halls of power. The Egyptian Center for Public Opinion Research (Baseera) documented this decline in popular support, showing a significant drop in Morsi’s approval rating and an increasing unwillingness of the majority of those polled to reelect him were presidential elections held now.

As the Tamarod campaign gained momentum, political actors began to sit up and take notice. Last week campaigners received a significant upsurge in support when the Egyptian Federation of Trade Unions, the Dostour party, and a number of prominent opposition figures, including National Salvation Front leaders Mohamed ElBaradei, Amr Moussa, and Hamdeen Sabbahi, backed the initiative. First secretary of the Journalists Syndicate, Gamal Fahmy, also announced his participation in Tamarod, reflecting the sense of resentment felt by journalists at the assault on free expression at the hands of security forces, the public prosecutor, and the Muslim Brotherhood under Morsi’s rule. The April 6th youth movement, and even former presidential candidate Ahmed Shafiq, also threw their support behind Tamarod.

Of course the campaign is not without its detractors. As the first respondents, not surprisingly, Morsi’s Freedom and Justice Party (FJP) dismissed the campaign as irrelevant. Within days of Tamarod’s emergence, Muhammad Zakariyya Shaaban, a senior member of the FJP, was quoted saying, “The Tamarod campaign is illegitimate and deviates from the principles of democracy… especially since Morsi is the elected president.” When asked last week, the president’s office refused to comment on the initiative. Most recently, Mohamed al-Beltagy, a well-known Muslim Brotherhood leader and member of the executive committee of the FJP, called the campaign a “mere survey,” and challenged its organizers to translate the signature into political support. The largest Salafi political group, the Nour Party, also rejected the initiative, calling it illegal and unconstitutional.

But if the campaign were so irrelevant, why bother with the expense of taking its organizers, journalists, and prominent opposition supporters to court? In a manner too typical of Egypt’s post-uprising political intimidation, Ashraf Nagy, a pro-Morsi lawyer responsible for one of the lawsuits brought against Bassem Youssef, submitted a complaint to the public prosecutor, Talaat Ibrahim. In it, he accused ElBaradei, Sabbahi, April 6th Youth leader Ahmed Maher, and Mahmoud Badr (the general coordinator for Tamarod) of attempting to overthrow the regime. Ibrahim also recently referred similar cases against journalists and campaigners to the state security prosecution office. Clearly, someone in Egypt’s leadership fears this enough to make it a national security issue.

Despite the energy and the enthusiasm surrounding this campaign, Beltagy’s assessment is not far from the truth. Morsi is indeed an elected president, however one may feel about his ability to govern. The constitution contains no mechanism by which to remove a sitting president before the end of his (or her) term. If Tamarod actually achieves its goal of raising 15 million signatures by the end of June, there is no body or institution to which it could submit the names and demand a new election. That does not imply, however, that the campaign is meaningless.

Even without reaching the full 15 million signatories, the campaign highlights – and exacerbates – the crisis of legitimacy facing Morsi by quantifying outspoken opponents to him, his government, and his party. The hyperbolic momentum would no doubt frighten the steeliest of political strategists, particularly given the clear demonstration of anti-Morsi sentiment that runs directly counter to the typical government rhetoric that claims popular support. A crackdown on the movement could slow the momentum but could also spark the kind of civil unrest that Morsi is trying to avoid, providing ammunition to campaigners and political opposition groups.

Some have suggested that the political opposition could use Tamarod to galvanize support for the upcoming parliamentary elections scheduled to take place in the fall. This theory could have some merit, but is not without its challenges. After an initial rejection of Shafiq’s endorsement of the campaign, the organizers issued a “clarification” that backtracked on the position, saying that they aimed to set aside political differences to serve all Egyptians in the hopes of ending Morsi’s rule. Unlike previous youth driven initiatives that have rejected overt political party or “felul” involvement, this campaign seems to soften this traditionally hard and fast line. If the political opposition can agree on a unified strategy and unified candidates (a big “if”) without falling apart, Tamarod has the potential to boost gains in the parliamentary elections. On the other hand, Egyptians are fickle and a failure to reach its goal or pressure a major concession out the Morsi government could result in the movement fizzling out. The timeframe between now and elections could deal a deadly blow to the movement.

Despite the impressive response garnered by the Tamarod campaign, it will not end in early presidential elections, no matter how many signatures they collect. Nonetheless, it could elicit a significant political shift. If the campaign can push voters towards a more balanced parliament, the potential for meaningful constitutional changes, via an agreed upon amendments process, could swing the odds towards the political opposition. It might even add a provision on the terms of early elections, shifting power away from the presidency. Morsi may have temporarily abandoned the active pursuit of political consensus in recent months, but a quantitative measure of his opposition could affect what legitimacy he still holds. The cases brought against journalists and political activists suggest that Tamarod is a risk Morsi is unwilling to take.

Tarek Radwan is the associate director for research at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center.

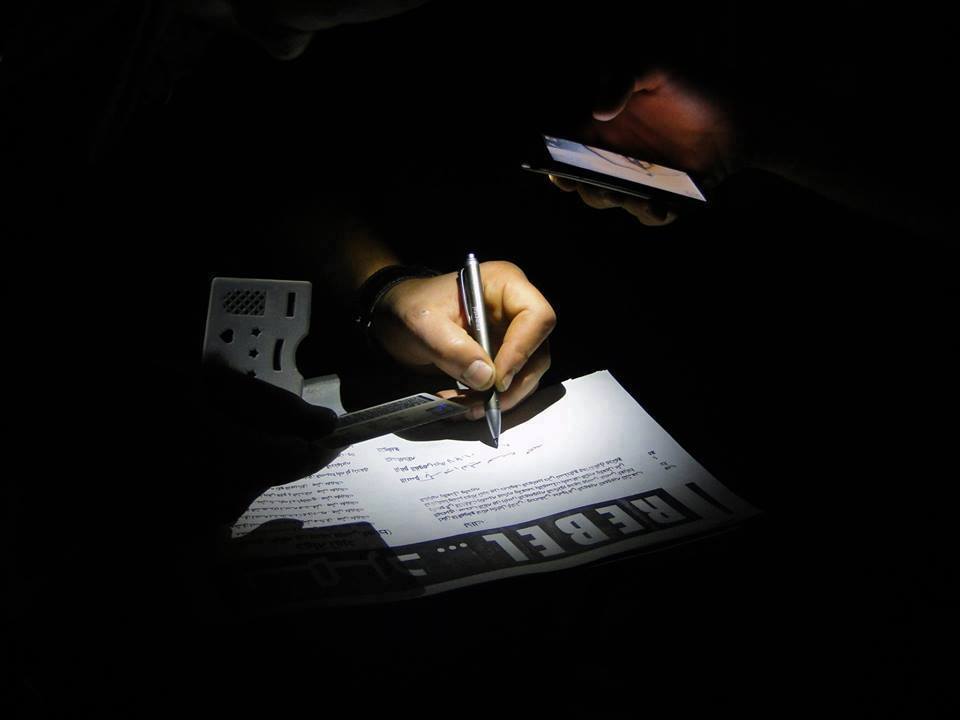

Photo: Tamarod

Image: Tamarod.jpg