The February 7 deadline for the General National Congress (GNC) has passed with news trickling in of a handful of legislators resigning in protest but no significant movement to shake the country out of its political paralysis and regenerate momentum for its transition to democracy. The streets, however, are grumbling as political maneuvers continue. Three critical dates approach on which Libya’s trajectory hinges. That these crucial decisions must be taken in a span of less than a week in a country where institutions lack capacity and elected bodies lack leadership sparks fears of a serious collapse of a politically negotiated transition.

The February 7 deadline for the General National Congress (GNC) has passed with news trickling in of a handful of legislators resigning in protest but no significant movement to shake the country out of its political paralysis and regenerate momentum for its transition to democracy. The streets, however, are grumbling as political maneuvers continue. Three critical dates approach on which Libya’s trajectory hinges. That these crucial decisions must be taken in a span of less than a week in a country where institutions lack capacity and elected bodies lack leadership sparks fears of a serious collapse of a politically negotiated transition.

February 14: Civil society organizations, inexperienced but enthusiastic, are tirelessly organizing themselves to launch mass demonstrations on February 14 against the GNC to call for new presidential and legislative elections to be held as soon as possible. Skeptics may question the efficacy of such an approach, considering the disparate nature of demonstrations held in Libya leading up to the GNC’s expiration date. While they have been numerous, the turnouts have been less than impressive.

Observers should bear in mind, however, that activists are operating in a climate of intimidation. Tensions escalated in the lead up to what was supposed to be the dissolution of the legislature, including with the Grand Mufti discouraging action against the GNC. Legislators are not yet entirely off the hook, however, as opposition among civil society groups rises over the passage of an amendment to the penal law sentencing anyone seen as insulting the GNC, government, or judiciary to jail time. The brewing anger could culminate on February 14 in a compelling show of outrage in the Libyan streets.

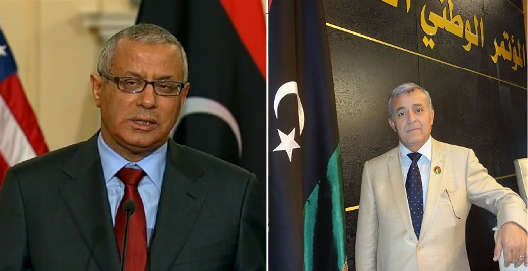

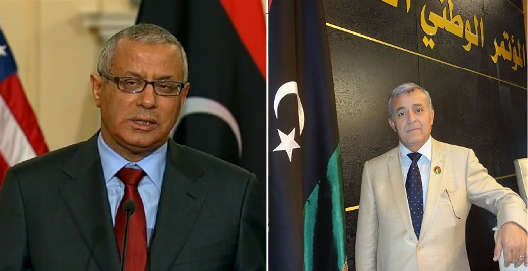

February 17: With the legislature still intact, GNC members resume their efforts to oust Prime Minister Ali Zidan. Legislators claim to have the votes they need to pass a no-confidence measure and have given Zidan until February 17 to resign; otherwise, they will force him from office.

Zidan has a few options to maintain his grip on power. He could continue to manipulate the divisions within the legislature and convince enough GNC members to side by him, preventing the GNC from reaching the necessary vote threshold. Although the GNC claims to have the votes, Zidan could potentially drive a wedge between the blocs and undermine their moment of unity in the context of weak party politics and dubious individual allegiances.

Alternatively, Zidan could simply ignore the GNC, invoking the February 7 deadline for its dissolution, dismissing the body as illegitimate, and rendering its calls weightless. It appears Zidan may already be using this tactic; despite news reports that the prime minister submitted his cabinet reshuffle proposal on February 9, private conversations reveal he is pushing back against this narrative, saying the legislature approved the nominations before February 7.

One last option, and most destabilizing, would involve Zidan’s reliance on armed support to stay in power. Shifting militia alliances make such an option highly unpredictable. A good part of the Zintani militias, including the Qaqaa, remain neutral, thereby lending tacit support for Zidan’s administration. Rumor has it this stance could be a result of backroom business dealings between the militia and the government. Should the arrangement provide enough incentives, Zidan may wield sufficient manpower to withstand pressure from the GNC to resign.

February 20: Elections for the constitutional committee are set for February 20. A wide cross-section of the Libyan polity questions the legitimacy of the committee that will eventually be formed. The severely limited allocation of seats for women and minorities has drawn criticism and ire; the Amazigh have effectively boycotted the system by not putting forth any candidates. The equally divided composition among the regions enshrined in the electoral law would see the least populated parts of the country acquiring outsized representation in the committee. With only an estimated one million voters registered (one third of whom cast their ballots in the July 2012 GNC elections), concerns over equal representation in the committee arise. Despite these concerns, civil society organizations have launched an ambitious public awareness campaign to promote transparency and accountability by publishing candidates’ positions on a range of social and political issues.

The government and the GNC are both responsible for the failures to respond to the dire situation gripping the country. As their credibility erodes, security continues to deteriorate and criminal activity escalates in the absence of a strong state. Political leaders risk plunging Libya deeper into chaos and pushing it farther from its international partners. The greater the disconnect between the state’s institutions and the Libyan people, the greater the threat to state legitimacy; and the more the state demonstrates its inability to harness aid from its international partners, the more likely that Libya’s allies will question whether their resources are worth expending.

Citizens bearing the burden of this paralysis drive the reversal of this trend toward positive change, beginning with the anticipated demonstrations later this week. As these critical dates approach, Libya’s institutions will need to respond to the people’s calls to keep the transition on track, even if that requires stepping down and appointing or electing new, credible Libyan leadership to the helm.

Karim Mezran is a resident senior fellow with the Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East focusing on the processes of change in North Africa. He is currently reporting from Italy and Libya researching the latest developments in Libya’s transition.

Image: Libyan Prime Minister Ali Zidan and GNC President Nuri Abu Sahmain. (Photo: US Dept. of State, Wikimedia)