Decades of arguments and analysis continue to discuss whether Arab citizens actually want democracy, whether they are “ready” for it, if appropriate conditions exist for democratic rule, and so on. Fortunately, two recent polls offer answers to some of these questions. Their results demonstrate how important Arabs consider the pursuit of democracy to be relative to other national priorities.

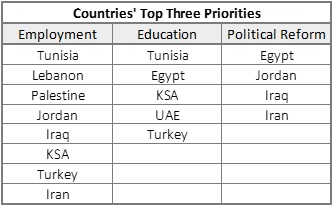

In August and September of 2018, Zogby Research Services surveyed 8,628 adults across Tunisia, Egypt, Lebanon, Palestine, Jordan, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Turkey, and Iran. Respondents in each country were asked to distinguish and rank their top three priorities from a list of ten issue areas.

In eight of the ten countries surveyed, participants judged “expanding employment opportunities” as the most important issue, while “improving the educational system” and “political and governmental reform” also garnered significant attention. Beyond these three priorities, countries disagreed on the relative importance of the following issue areas:

- ending corruption

- combatting extremist groups

- warding off foreign enemies

- improving health care

- protecting personal rights

- improving women’s rights

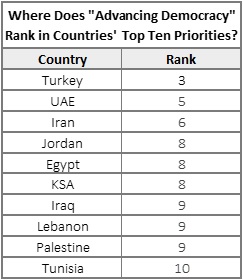

Notably, out of the ten states canvassed, only Turkey ranked “advancing democracy” as a top three priority. These results are not surprising. Even during the turbulence of 2011, survey respondents regarded employment as their highest concern, while only participants in Tunisia and Iran ranked democracy among their top three priorities.

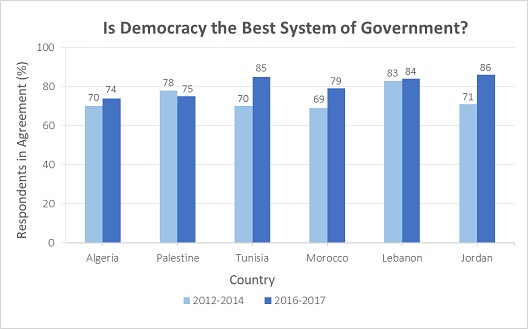

Some might interpret the survey results as demonstrating a lack of demand or a lack of belief in democracy on the part of Arabs. They would likely be wrong, or at least be selectively using data that supports their views. Results from the Arab Barometer’s 2018 survey demonstrate, for example, that Arabs increasingly consider democracy to be the best system of government. Other data in the report demonstrates how popular perceptions and other priorities may be impeding the actual pursuit of democracy in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) countries.

The immediate pursuit of democratic political systems was not listed as a top three priority in either data set. By ranking “expanding employment opportunities” and “political and governmental reform” above “advancing democracy,” respondents seemed inclined towards a better economic status and a go-slow approach to political change. While it is difficult to draw firm conclusions from the data, it would not be surprising if the results reflected general wariness towards the instability of democratic movements seen in Egypt and Tunisia.

However, it should be repeated that this disinclination for rapid change does not imply Arab fear of or distaste for democracy. Arab attitudes towards the system of democracy appear to be overwhelmingly positive; in the two most recent waves of Arab Barometer’s polling, all six Arab countries surveyed demonstrated a strong—and growing—acceptance of democracy as the best type of government.

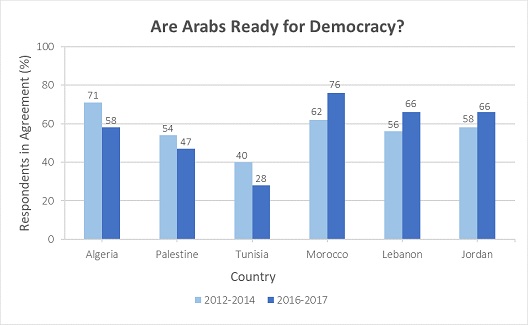

But do Arabs believe are they ready? According to the same Arab Barometer data, there has been an increased perception since 2014 that people in Palestine, Algeria, and Tunisia are not ready for democracy. This trend coincides with other data from the same report; in particular, these three countries happen to be the states most skeptical about democracy’s stability and economic payoffs. Meanwhile, Morocco and Jordan, where respondents expressed greater faith in democracy’s provision of stability and economic benefits, were the countries most confident in their suitability for democracy. In sum, some Arabs believe democracy is “ineffective in maintaining stability,” others believe lack of representative government is an “obstacle to stability.”

By juxtaposing Palestine, Algeria, and Tunisia against Morocco and Jordan, one may wonder why countries from the same region possess such contrasting attitudes towards democracy and its effects. Perhaps this phenomenon can be explained by the extenuating circumstances surrounding the first set of countries. It could be argued that Algerians, most of whom consider the country to be less democratic in 2017 than in 2014, glean their opinions about democracy from their geographical neighbor, Tunisia. If this were the case, both Algerians and Tunisians may feel less prepared for democracy now because the latter was shaken by the instability of its transition towards democracy in 2011.

This instability was particularly impactful in Tunisia—and not necessarily in Morocco or Jordan—because Tunisians lack significant trust in political leaders and institutions; more trust could have made the democratization process more stable. Meanwhile, Palestinians’ unpreparedness could be attributed to the unique difficulties of democratizing amid enduring political divisions and the ongoing Israeli occupation. However, these explanations are extrapolated from separate Arab Barometer and Zogby Research Services data sets and therefore, fall into the realm of informed speculation. For example, Algerians’ reliance on Tunisia as a political archetype could be overestimated.

There are other ways to explain MENA’s varied attitudes towards the process of democratization. Another potential explanation attributes Moroccan and Jordanian feelings of preparedness to incomplete democratic transitions. In theory, Morocco and Jordan’s monarchies hold competitive elections and attempt to alter citizens’ perceptions of their regimes. However, these reforms may not be as democratic as they try to appear, as evidenced by waves of reignited protests across Morocco. This explanation assumes that only countries like Tunisia and Lebanon have experienced the upheaval associated with true democratic transitions and can accurately understand their suitability for democracy. Of course, this prediction has its own limitations, one being the inability to concretely quantify democracy, especially as Moroccans and Jordanians both believe their states are more democratic now than in prior years.

While it certainly needs far more analysis than could be provided here, this data has implications for those outside the region who support and promote democratic change be they governments, NGOs, or concerned citizens who simply believe in democracy. Monarchs and dictators in the region would also do well to take note of the data.

The first observation we would draw from the data is that Arabs have decidedly not rejected democracy as a form of government suitable for them. Second, MENA countries need to respond to the unfulfilled economic aspirations of their people. It is consistently the top priority across the Arab world. Third, we should not confuse prioritization of material well-being with disinterest in progress towards democracy. Arabs surveyed expect more from their governments, as indicated by the constant interest in political and government reform, and by the abiding belief in the idea of democracy as the best overall political system.

Ambassador Richard LeBaron is a Non-Resident Senior Fellow at the Hariri Center who served in senior diplomatic postings in the Middle East.

Leah Hickert was a research intern at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center and is currently studying Middle Eastern peace and security issues at Boston College.

Image: Demonstrators gesture and chant slogans during a protest demanding the removal of the ruling elite in Algiers, Algeria August 2, 2019. REUTERS/Ramzi Boudina