Since the rapid expansion of the Islamic State (ISIS or ISIL) into Syria and Iraq, global leaders have struggled to understand the nature of support for extremist groups from local and international youth. ISIS affiliates have sprung up across the Middle East, including in Egypt where the government has waged a low intensity war with terrorist groups—particularly in the Sinai Peninsula. Egypt’s National Council for Human Rights reported that, since the ouster of ex-president Mohamed Morsi until the end of 2014, 700 members of the security forces have died.

In the subsequent six months, Egypt saw a surge in terrorist activity and most recently witnessed the most coordinated attack yet by the Sinai State, militants affiliated with ISIS, in the northern Sinai town of Sheikh Zuweid. In January, President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi called for a revolution in religious discourse in an attempt to combat violent extremism. Given the rise in frequency and intensity of attacks throughout Egypt since that time, a closer look at the religious arm of the government—the Endowments Ministry—may help shed some light on Sisi’s soft-power strategy to fight extremism.

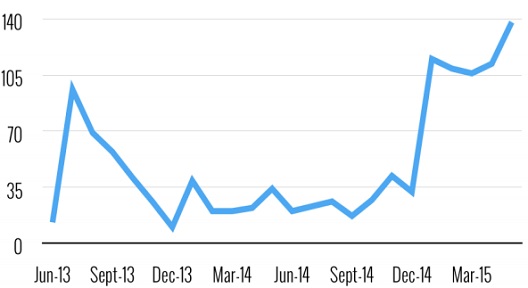

Source: Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy, “Egypt Security Watch Monthly Briefing 8: May 2015,” Table 5. Number of attacks countrywide.

Up until the January 25 uprising, Egypt faced a growing problem of unregulated mosques and unlicensed preachers spreading throughout the country due to underfunding. The problem worsened under Morsi as Muslim Brotherhood members and Salafis used mosques and the Ministry for political purposes. Nearly a year after Morsi’s ouster in June 2014, then-interim President Adly Mansour issued law 52/2014 regulating sermons and prohibiting those without government approval from preaching. In one of his first major policy actions, Gomaa revoked the licenses of about 55,000 imams. The Ministry said the ban targeted small, unlicensed mosques whose imams had incited violence, and also aimed at ensuring a moderate message coming out of Egypt’s mosques. Imams were given the opportunity to request a new license on the condition they held a degree from Al-Azhar or other state-affiliated institutions. The Ministry also replaced administrative boards of many larger mosques in an effort to stamp out Muslim Brotherhood influence.

After the Brotherhood’s use of the pulpit to promote the groups policies and ideology, the end of 2013 saw a focus on a policy prohibiting the use of sermons and mosques as a political platform. Endowments Ministry inspectors have rigidly enforced this provision, most recently, with the suspension and travel ban of one of Egypt’s most popular imams, Sheikh Mohamed Gibril. In a sermon during one of the holiest nights of Ramadan, Gibril prayed for protection against the “corrupt media, and the obscurantism of rulers,” which drew enthusiastic cries of amen from the approximately 10,000 worshippers gathered there. Media figures struck back, accusing him of praying against the nation and sympathizing with the Muslim Brotherhood, despite no explicit support for the group. The Endowments Ministry took an aggressive stance against the popular imam, with the Minister himself vowing in a televised interview that Gibril would never preach in Egypt in his lifetime and calling on all countries fighting terrorism to uphold the ban.

The Ministry has not limited its stance toward those it suspects of being Muslim Brotherhood sympathizers, but also extended its authority to block Islamists without ties to the group from preaching. Only a day earlier, two influential Salafi preachers, Mohamed Hassan and Mohamed Hussein Yakoub received word that they could not deliver sermons for Eid al-Fitr, the holiday at the conclusion of Ramadan. The Endowments Ministry released a statement saying that the imams could not preach without a license, adding that Yasser Borhamy, the deputy head of the Salafi Call, was the only person from the organization authorized to do so. It warned that government officials, in concert with security forces, would raid any unauthorized gatherings.

In addition to acting as a government watchdog on preachers, the Ministry has also proactively sought to destroy literature and audio materials in mosque libraries that incite violence and radicalism and monitor schools suspected of Muslim Brotherhood administration. Gomaa issued an order in June for all mosques to submit a list of library materials and abide by the requirement for government approval of any new materials. Although the head of the Ministry’s Religious Affairs Department Mohamed Abdel Razeq had publicly admitted to issuing orders to burn these and other books authored by Muslim Brotherhood figures, the Ministry website later denied this claim. In April, Gomaa also scrutinized private schools allegedly under alleged Muslim Brotherhood control, calling for authorities to place them under immediate surveillance and a replace their administrative boards to prevent “the prevalence of some Islamic cultures that do not belong to Al-Azhar or the ministry’s supervision.”

Although most government policies have focused on squeezing the Brotherhood from the religious sphere, some Endowments Ministry programs have tried to tackle the challenge of moderating and modernizing religious speech. In May, the Ministry held a conference to address Sisi’s call for a revolution in religious discourse specifically. Both the Ministers of Culture and Sports attended in an effort to reach out to Egyptian youth. In exploring new ways to discuss religion, Sports Minister Khaled Abdel-Aziz said, “If we want to reach out to them [the youth] we need to use the same modern tools of communication they use.” This sentiment may explain an attempt to train 300 preachers to use online social messaging to provide government support to imams confronting extremist rhetoric.

Nonetheless, such efforts seem to stumble as the Endowments Ministry struggles to reconcile a proselytizing message with Sisi’s desire for renewal. In April, the Ministry launched an effort to form anti-atheism awareness groups. “The gatherings aim at spreading awareness on the threats of atheism, Shia, Bahaism expiation, killings, and drug addiction,” said spokesperson Mohamed Abdel Razeq, illustrating a different understanding of religious moderation than perhaps that to which Sisi had suggested in his January speech to Al-Azhar.

While the Ministry of Endowments has taken steps to try to satisfy Sisi’s call for a revolution in religious discourse, it clearly reflects the attitude of the Sisi regime in its sentiment toward the Muslim Brotherhood. As part of a whole-of-government effort to confront any destabilizing efforts by the Brotherhood, the Ministry has mobilized to deny Brotherhood figures a sphere of influence within the religious community to agitate against the state. Along with Sisi and other government and security officials, Gomaa has repeatedly adopted the narrative equating the Muslim Brotherhood with terrorism and extremism—that the fight against the banned group is the fight against terrorism.

The Endowments Ministry’s efforts appear to continue its two-year policy geared toward enforcing government control over the religious sphere—an important policy to hold preachers accountable for their religious rhetoric. Yet an overemphasis on denying the Muslim Brotherhood (or other Islamists and political dissidents) a sphere of influence, the apparently clumsy efforts to modernize religious discourse through technology, and some inconsistency on the understanding of religious moderation have not yet achieved the stated aim of helping Sisi combat radicalism and terrorism.

Tarek Radwan is Associate Director for the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

Image: Photo: Youm7