The previous article reviewed the likely reactions of two of the Arab states which neighbor Libya—Algeria and Tunisia—should a joint Arab intervention be proposed in order to put an end to the worsening crisis in Tripoli. Of the Arab states neighboring Libya, Sudan is the only one whose predicted reaction to a joint Arab intervention in Libya remains to be analyzed.

The previous article reviewed the likely reactions of two of the Arab states which neighbor Libya—Algeria and Tunisia—should a joint Arab intervention be proposed in order to put an end to the worsening crisis in Tripoli. Of the Arab states neighboring Libya, Sudan is the only one whose predicted reaction to a joint Arab intervention in Libya remains to be analyzed.

Many of the interests of the Omar al-Bashir regime are tied up with the Muslim Brotherhood in one form or another, both domestically and internationally. There is no doubt that the Sudanese regime was negatively affected by the sudden wave of attacks against the Muslim Brotherhood which swept the Arab region and took back much of the ground gained by the organization following the Arab Spring uprisings. The clampdown in Egypt – the Brotherhood’s birthplace and stronghold – was particularly damaging to Khartoum. Indeed, Bashir had been preparing not only to move beyond his traditional stance of isolation by expanding engagement with Cairo, Tripoli, and even Tunis, but also to achieve a unique integration between these four Brotherhood-led regimes, which would collectively govern both the vastest territory and the largest human population in the entire Arab region. With the dramatic collapse of the Brotherhood regimes in Cairo and then in Tripoli, however, Bashir was shocked into realizing that his regime was not immune to being subjected to the same fate.

Any Arab intervention in Libya to eliminate the threat of armed groups, including takfiri groups, would certainly not end in such a way that the Muslim Brotherhood would be able to return to power. Rather, the matter would undoubtedly be settled in the favor of groups antithetical to the Brotherhood. This means that, if necessary, the Bashir regime will intercede directly to prevent such an intervention from occurring.

Two weeks ago – in a development indicating that the conflict in Libya had reached new levels – the Libyan government that was established by the new parliament issued an official statement in which it blatantly accused the Bashir regime of involvement in supplying weapons to certain armed groups in Libya. According to the official statement, a Sudanese military transport plane had entered Libyan airspace without authorization or an official request from the Civil Aviation Ministry.

In its statement, the Libyan government declared: “This act by the state of Sudan represents a breach of Libyan sovereignty and an intervention in Libyan affairs. Through its support of a terrorist group seeking to undermine the Libyan state and its provision of arms to this group, Sudan has committed a flagrant violation of international resolutions, the most recent of which was a resolution adopted by the UN Security Council to impose an arms embargo on Libya.”

*********************

In light of the reactions of these Arab countries to the prospect of a joint Arab intervention in Libya – which at best reflect serious reservations and at worst outright opposition to such an intervention and even support for armed conservative groups within Libya – Cairo would clearly not be able to depend on any of these countries if it were to pursue either a direct or indirect intervention in Libya. The only support that Cairo would be able to count on is that of its strategic partners in the Gulf: namely, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

The reality is that the strategic alliance that crystallized over the past year between Egypt and its Gulf counterparts of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain must be prepared to overcome numerous challenges in the near future. These challenges will test the mettle of this alliance; its cohesion and durability, in addition to its ability to expand naturally and incorporate other states.

This alliance is based first and foremost on a philosophy of mutual defense, according to which Riyadh and Abu Dhabi provide economic support to the new Egyptian regime in order for it to confront its enemies and critics and achieve internal stability. In return, Cairo adopts security in the Gulf – a region that faces numerous threats both from within and from abroad – as a top priority.

Despite the established commonalities that led to the creation of this alliance, it will be necessary for the alliance to define its strategic priorities and to unify its vision regarding how to confront the challenges facing the region in order to remain intact and incorporate additional states as partners.

Nevertheless, the perspectives of these three states on how to deal with the Gaza crisis are less congruent than is the case with regards to the situations in Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria, even though there is some common ground.

Indeed, the gap between the respective national security considerations of these states is narrow and may appear to be closing even further, to the point that the security calculations of the members of this alliance will soon become completely unified. In effect, this should mean that the alliance will become integrated into a joint defense system. However, the current reality is that the Egyptian regime, for instance, faces a strategic problem within this alliance due to its prioritization of its confrontation of takfiri militias.

For Egypt, the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) appears the remotest of the threats currently facing the country – despite the possibility that some scattered, ineffectual takfiri groups in Egypt could become ideological followers of ISIS, even as the Egyptian army’s next confrontation will almost surely be against takfiri groups along Egypt’s western border with Libya. From the perspective of the Gulf members of this alliance, however, the tremendous spread of ISIS militias in Iraq and Syria appears much closer to home. These divergent perspectives threaten to divide the alliance’s efforts across two very distant fronts.

The scenario of direct engagement in traditional warfare on the three fronts is likely to be officially dismissed, at least from the options being considered by this alliance, due to the considerations referred to above and because of the likely depletive effects of such a scenario. Another deterring factor is that internal conflicts are raging on at least two of these fronts (Libya and Yemen), which would result in fierce popular resistance to intervention by this alliance. Rather than being perceived as a liberator, as was the coalition that intervened in the crisis in Kuwait, the alliance would be seen as an occupier and likened to Iraq under Saddam Hussein.

It is most probable that the alliance will resort to proxy warfare, even if such a strategy proves insufficient in the short term to put an end to conflicts between parties of relatively equal strength, as is currently the case in Libya. In order to compensate for this, Cairo may be forced to significantly develop the traditional understanding of proxy warfare to include direct logistical support (providing supplies, preparation, and training), full intelligence support (providing necessary information, conducting psychological warfare, and penetrating armed groups), and perhaps even conducting unofficial special operations, if required to tip the balance in decisive battles.

*********************

The most significant obstacle preventing such a scenario in Libya is the severe internal divisions within the country and Libyan society’s fragmentation into multiple competing parties, all of which are severely suspicious of each other. This is particularly true in eastern Libya (Benghazi and the surrounding areas), where most of the fighting is taking place. This region was historically marginalized during Qaddafi’s rule, and it was this region that bore the brunt of the cost of the revolution. Now, eastern Libya will not easily cede leadership again to Tripoli without guarantees that it will not face a situation similar to that experienced under Qaddafi.

In this context, efforts to bring about national reconciliation and to unify Libyans, as well as attempts to disarm all militias in order to save Libya from becoming a failed state, are seen as an attempt by Tripoli to impose its dominance once again and to rob other tribes and groups of their economic resources.

Anyone who imagines that the current conflict in Libya is limited to a struggle between the state and takfiri militias – as is the case in Egypt, for example – is gravely mistaken. There are currently any number of points of conflict in Libya, including political influence, power and domination, economic and financial gains, revolutionary legitimacy, and even Libyan identity.

In a BBC news report, Dr. Hussein Oraibi, a member of the local council of Tajura who served as the media representative of the National Transitional Council during the revolution, stated that following the revolution, the transitional government inherited a weak state and that the government further undermined this state through its “lack of any decisive action by the Libyan [government]” to put an end to the influence of militias.

Meanwhile, Abdullah al-Thani (one of the two disputed prime ministers in Libya) holds a different view, asserting that it was the strength of these militias that prevented the state institutions from developing their roles, not the weakness of the state that allowed militias to impose their control.

In an interview with BBC last month, Abdullah al-Thani emphasized that the quantities and types of weapons that these militias possess – including “tanks, artillery, rocket launchers, and missiles” – surpass the capabilities of the state. “Through these weapons, militias became more powerful than the state and began to take over the role of the state in maintaining peace and security.”

*********************

The very term “militias” does not accurately describe the reality in Libya, as many of these armed groups officially belong to the ministry of defense or ministry of interior and their members receive salaries from the state. However, these groups do not always follow orders issued by the state and at times become a security problem.

While some militias do provide services related to maintaining security and order in their respective regions, others profit from the drug trade, human trafficking, and oil sales or carry out abductions for the purpose of blackmail. Many militias are also guilty of illegally detaining and imprisoning numerous individuals, as was confirmed by a statement made by a former Libyan official – on the condition of anonymity – to BBC.

The most difficult task now is finding a Libyan partner in the midst of all of this fragmentation who enjoys the necessary minimum level of consensus to make it possible to engage via proxies in the fighting in Libya.

Nader Bakkar is a co-founder of Egypt’s al-Nour Party and serves as a member of the party’s presidential and foreign affairs committees, as well as the chairman’s assistant for media affairs.

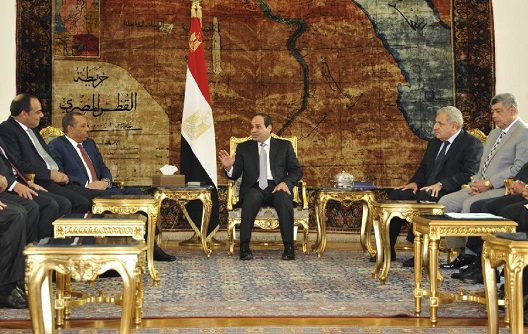

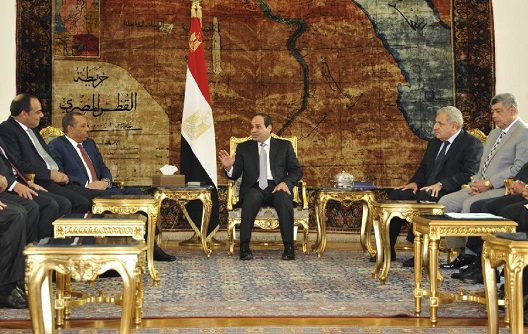

Image: Photo: Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi, center, meets Libya's interim Prime Minister Abdullah al-Thinni, second left, in Cairo, Egypt, Wednesday, October 8, 2014 [MENA]