For decades, Egypt focused primarily on its foreign policy in the Middle East and North Africa, and in the process neglected its Horn of Africa policy. Meanwhile, Ethiopia began construction on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Nile River. Problems along the Nile continue for Egypt as droughts, rising temperatures, and general effects of climate change demand a response to Egypt’s growing water needs.

In 2013, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El Sisi acknowledged that the Nile was fast becoming the largest threat to Egypt’s security. Despite wide diplomatic outreach to countries across the region, with construction of the GERD nearing completion, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan—the “Tripartite”—are as far from an agreement on the future of the Nile as they were when the dam was first proposed. Now Egypt’s silence threatens its identity and heritage: access to the Nile River.

But what is the crisis? And what does it mean for Egypt?

Egypt is a water-scarce nation. As its population continues to rise at an unsustainable rate—almost 2 percent per annum—Egypt’s water needs now heavily outweigh its access and usage. The GERD has become the symbol of that water scarcity.

It is certainly easy for Egypt—its people and its government—to point the finger at Ethiopia and blame it for any impending water shortages. Without a doubt, the GERD, a hydroelectric dam, and the filling of the reservoir—up to 74 billion cubic meters—will directly impact Egypt and decrease its current share of the Nile River.

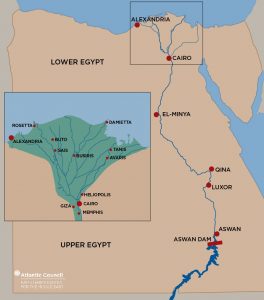

The river itself also remains a sensitive domestic issue, as it is the symbol of historic ethnic tensions in the country. Discrimination against a sizeable Nubian population continues, following its displacement by the construction of the Aswan Dam in the 1960s, robbed of its farming heritage, and still demanding the right to return to its lands.

Yet Egyptian politicians and leaders continue to ignore the stark realities of Egypt’s water wastage, the mass amounts of water already lost to evaporation at the Aswan High Dam, the non-existent water pricing policies for its farming community, and the lack of widespread advanced agricultural technology.

Egypt continues to plant water-intensive rather than value-added crops that could generate income through export to international markets while decreasing its water usage.

In an effort to curb the production of water-intensive crops, the government pre-emptively banned up to 75 percent of rice production across the country to prepare for the expected decrease in water. The decision provides no recourse or alternative income for farmers, nor does it police or monitor production. Some farmers will likely continue to cultivate rice using water-intensive irrigation methods because farmers in Egypt are not charged for water usage.

Egypt’s leaders continue to view farming and agriculture through the lens of domestic consumption and the need to feed its own population; particularly urban communities. The current agricultural model is simply unsustainable. Egypt will be heavily impacted by the GERD. The question is by how much.

The “fill” debate:

The 2015 Declaration of Principles, signed by the Tripartite countries in Khartoum, was a diplomatic success for Egypt. It committed Ethiopia to undertake independent studies of the project’s impact, fill timeline, and usage of the dam. However, Egypt is still struggling to reach a diplomatic settlement with its African partners. The primary concern is that the Tripartite has not reached an agreement on the GERD reservoir’s contentious “fill” time—the schedule for filling the reservoir behind the dam—and what the consequences of decreased water access look like for the Egyptian economy and society.

The fill time is expected to decrease Egypt’s water supply by 10 percent over six years. This would devastate a significant amount of the farming industry along the Nile. Egyptians tried to impose a fill time that would last over twenty years to lessen the negative impact on farms, but it is privately understood that the government has given up. Due to diplomatic and security disagreements, the Sudanese withdrew their support for Egypt (subsequent to the signing of the Declaration) and “switched sides” to Ethiopia. Jockeying for diplomatic favor by the Sudanese, and the recent change of leadership in Ethiopia, provides a new set of challenges for the Egyptians. Behind closed doors, Egyptians reluctantly conceded defeat and acknowledged the type of impact the country could see.

Egypt could find itself suffering in the long term, particularly if affected countries cannot reach a sustainable transboundary water agreement and further development occurs upstream, including more dams and reduced water flows for irrigation. Although experts warn that any threat to Egypt from Sudanese agriculture is wildly out of proportion, it does pose the biggest direct threat if realized.

It is expected that water loss in Egypt could affect approximately seven to ten million people who are connected to the land. The Upper Egyptian community is unlikely to be directly affected because it has direct access to the Aswan Dam, which will remain unaffected according to the Tripartite. It is expected that the Delta and Nile Valley lands will be the most affected. Indeed, they already are.

The effects of water scarcity are evident in the building permits given to farmers with swathes of land. Construction is a quick way to make money in an era of economic decline. As a result, residential construction is increasing and farms across the region are turning from green pastures to building blocks. Meanwhile, domestic farming output is decreasing. This is causing further knock-on effects, notably with the Delta’s rising salination levels, primarily as a result of rising sea levels.

What does this mean?

In realistic terms, the reduction of access to water does not need to be the existential fight that Egypt purports it to be. New technologies that use solar energy could be implemented to support the country’s farming community and bring in much-needed revenue for the country and balance its import and exports balance sheets.

Ultimately, the reduction of the farming community, with no recourse or alternative source of employment, can only add to the current social and economic pressures within the country. The domestic economic stresses are already immense. Adding more unemployed people to the growing numbers—and rising due to rapid population increase—will only exacerbate the crisis. For now, it seems there are no policy solutions from a government whose main response in the face of economic decline is to regularly impose austerity measures, despite the crisis that already exists.

But the issues of the GERD go far beyond domestic socio-economic effects. Politically, having imposed its “red line”—the zero-sum game of bringing Ethiopia’s policies in line with Egypt’s needs—Egypt finds itself caught between a rock and a hard place. Privately, it is known that the government accepts that there will be water shortages to come. Publicly, however, the government continues to argue that the construction and completion of the GERD will not affect Egypt in any way. The two are simply not reconcilable positions. In essence, the public message that leaders continue to send to the people remains divorced from reality.

The GERD is a major dilemma for Egyptians: the unilateral development of the River Nile by upstream countries, in the absence of any effective management agreement, is likely to have a detrimental effect on Egypt and its water access. From the Egyptian perspective, such activity—by Ethiopia or others—cannot be left to continue unchecked, with officials arguing that activity along the river constitutes a national security threat.

Egypt has a vested interest in ensuring that the GERD negotiations result in the recapture of its position as the powerful hegemon of the Nile, despite its positioning as the furthest downstream. While Egypt has seemingly missed the boat on attempting to get ahead of the GERD project and be an integral partner in its development, the economic opportunities that now exist as a result of the dam should not be ignored by the Egyptians.

As they move toward a resolution, parties should focus on the opportunities that exist in relation to electricity sales, food imports, and future potential to engage in joint development projects in agriculture that can benefit the Tripartite as a whole. Any agreements on the river should therefore include potential for joint economic engagement on river development, and future projects in farming, irrigation, and more advanced hydroponic technology.

The Tripartite should engage international allies, multilateral organizations such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund—including the Gulf countries—and friends of the Horn region to support the development of the region as a whole. Engaging countries invested in the GERD and support broader multilateral frameworks—to monitor and effectively manage the river itself—will provide the Tripartite with the required power to build towards a long-term agreement. If such an agreement is reached, it can survive the effects of climate change, and more importantly protect the interests of all the countries, while still unlocking the economic and environmental potential that exists. Such potential ultimately provides political security for all Tripartite countries.

Hafsa Halawa is a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East. Follow her on Twitter: @HafsaHalawa.

Image: Photo: A farmer flattens the soil using a horse to prepare his land for growing rice in the 6th of October village in the Nile Delta province of Al-Baheira, northwest of Cairo, May 22, 2014. For the past 15 years, antiquated irrigation systems and a government conservation drive have kept many farmers from nutrient-rich Nile waters, forcing them to tap sewage-filled canals despite their proximity to the world's longest river. REUTERS/Asmaa Waguih