This past weekend’s mass death sentences handed down to former Egyptian president Mohamed Morsi and more than 100 others is another stark reminder of the government’s relentless assault on all forms of dissent in Egypt. By far the biggest targets have been supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood, but also opposition figures, critics, journalists, and rights activists. Thousands remain jailed and continue to face prolonged, unfair trials.

This past weekend’s mass death sentences handed down to former Egyptian president Mohamed Morsi and more than 100 others is another stark reminder of the government’s relentless assault on all forms of dissent in Egypt. By far the biggest targets have been supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood, but also opposition figures, critics, journalists, and rights activists. Thousands remain jailed and continue to face prolonged, unfair trials.

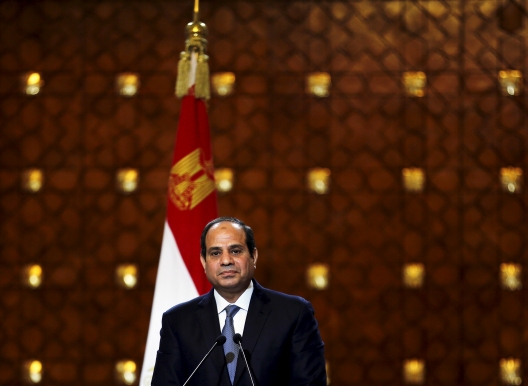

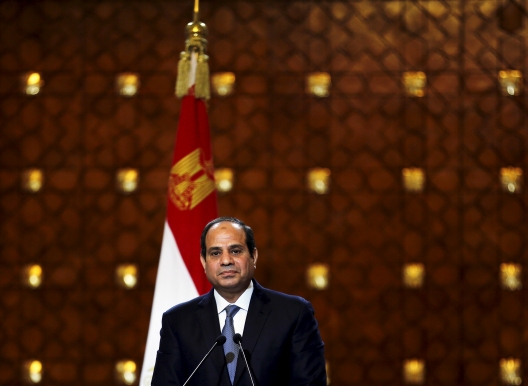

Next week marks one year since Abdel Fattah al-Sisi was elected president. While much media attention has been paid to his government’s controversial “war on terror,” and its dire consequences for civil society and human rights conditions in the country, less attention has focused on how Sisi’s government has responded to the Egyptian people’s right to freedom of religion or belief in a post-Morsi, post-Islamist environment.

Sisi’s decimation of the Brotherhood remains the hallmark of his tenure as both military leader and president. After Egyptian security forces killed hundreds of supporters in August 2013 – as well as suffering casualties themselves – the government branded the organization a terrorist group and the Egyptian judiciary has jailed thousands and imposed stiff prison terms and death sentences on hundreds. To date, seven executions have been carried out, six of which took place a day after Morsi was sentenced to death. To be sure, there have been legitimate and necessary government efforts to stamp out violent extremism, but the tactics used by the interior ministry and judiciary have resulted in numerous allegations of torture and sham trials with grave breaches of due process and little or no transparency.

While playing the familiar role of strongman, Sisi has cast himself as a reformer and leader for all Egyptians, regardless of belief or creed. His “religious revolution” speech in January, addressing senior Muslim clerics at Al Azhar, was a laudable call to reshape conservative religious discourse, combat religious extremism, and revise the country’s outdated and intolerant religious curricula, which is now underway.

He also became the first Egyptian president to attend a Coptic Christmas Eve mass. He demonstrated solidarity with Copts in the aftermath of the Islamic State’s killing of twenty Egyptian Christians in Libya, by consoling Coptic Pope Tawadros in person, declaring a week of national mourning, and telling Copts that so long as he is in power, they will have equal protection as citizens.

Assuming the best of intentions and Sisi’s ability to follow through, to rely on the favor of a single individual is to live precariously. What happens when the ruler passes from the scene or loses control? In an instant, safety and security for the most vulnerable can vanish.

Fortunately there is a better way, the way of ensuring robust protections for religious freedom. Rulers and regimes come and go, but when a society commits itself to religious freedom, the security of religious communities – as well as that of dissenters from religion – is guaranteed no matter who holds power. Granted, to embed religious freedom and other human rights in a society is no easy task, however, the authoritarian and Islamist alternatives have failed, repeatedly.

During multiple visits to Egypt since the January 25, 2011 revolution – under military rule, under Morsi, and now Sisi – I’ve repeatedly reached the same conclusion: the government’s continued restrictions on religious freedom is a powerful indicator that it will not make any measurable progress on larger democratic and political reforms.

Unfortunately, many of the current laws and policies that adversely impact religious freedom remain in place in Egypt despite an improved 2014 constitution and Sisi’s encouraging gestures.

In its annual report released last month, the US Commission on International Religious Freedom found that Sisi’s positive sentiment did not outweigh the lack of genuine reforms and recommended that Egypt be named a “country of particular concern” for continuing violations of freedom of religion or belief.

Under the pretext of combatting extremism, Sisi’s government has increased regulation and control of Islamic institutions resulting in the closure of thousands of mosques and stifling various interpretations within Islam.

While the number of violent sectarian attacks decreased over the past year, the Egyptian government did not adequately protect religious minorities, particularly Copts, and lack of prosecutions for past large-scale attacks – such as Alexandria, Imbaba, and Maspero – continued to foster a climate of impunity. For example, in March, local police failed to prevent a mob attack on a Coptic church in the al-Our village in Upper Egypt, the hometown of thirteen of the twenty Copts killed in Libya, where Sisi decreed a new church be built in their honor. The mob vowed they would not allow the new church to be built and damaged several Coptic homes and businesses in the area.

To its credit, during the past year, Egyptian courts held some perpetrators to account for unprecedented destruction in 2013 of more than fifty churches and dozens of Christian properties. Nevertheless, courts continue to prosecute, convict, and imprison citizens for blasphemy, and new government initiatives to counter atheism emerged during the year. While most blasphemy charges are leveled against Sunni Muslim dissidents, the majority of those sentenced to prison terms are Christians, Shi’a Muslims, and atheists, mostly based on flawed trials. Article 98 of the penal code, which is often cited to prosecute blasphemy cases, must be revised.

Nothing has changed for the small, peaceful communities of Baha’is and Jehovah’s Witnesses. They remain banned by fifty-five year old presidential decrees and the Baha’i community continues to suffer from public demonization, including by government entities. For example, in December, the Ministry of Religious Endowments held a public workshop to raise awareness about the “growing dangers” of the spread of the Baha’i Faith in Egypt. To date, Baha’is are forced to put a dash on identity documents in the required religion section since the only options remain Islam, Christianity, or Judaism. The once-thriving Jewish community numbering tens of thousands in the mid-twentieth century is now only a small remnant with fewer than twenty members remaining.

Sisi has issued dozens of presidential decrees since assuming office, yet he has not advanced a decree that would end a century-and-a-half-old discriminatory law requiring government approval for building or repairing churches, but not mosques.

Notwithstanding a presidential decree, a new parliament could implement Article 235 of the constitution – passing a law governing church construction and renovation – but nearly two years since Morsi’s ouster, parliament has yet to be seated.

Nonetheless, Sisi’s positive statements continue. In a recent media interview, he identified himself as a devout Muslim who “respects the freedom of the people to choose their own religious denominations or even to not believe in God in the first place.”

If Sisi translates his reformist words into concrete protections to every Egyptian, irrespective of religion or belief, then Egypt could be headed for better days. If not, he likely will be remembered as just another strongman, at the expense of the Egyptian people.

Dwight Bashir is Deputy Director of Policy and Research at the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. The views expressed here are the author’s own. On Twitter @DwightBashir.

Image: Photo: Reuters/Amr Dalsh