Egypt’s ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), catapulted from the barracks to the executive branch after removing Hosni Mubarak last year, has faced a steep learning curve in unfamiliar political territory. While the SCAF continues to display ineptitude in handling a series of crises, most recently the soccer-related violence in Port Said and the diplomatic fallout over the investigation of American-funded NGOs, the SCAF has pulled one tactic out of the Mubarakist playbook: the good cop/bad cop game. As the U.S. Congress threatens to suspend Egypt’s 1.3 billion military aid package over the politically motivated indictment of 19 American NGO employees, the SCAF has found a convenient scapegoat to deflect the blame: an allegedly independent judiciary.

When U.S. Ambassador Anne Patterson sent a letter to the Justice Ministry in late January urging Egypt to lift the recently imposed travel ban on six Americans working for NGOs in Egypt, Judge Sameh Abu Zeid rejected the request as “unacceptable” interference in the judicial inquiry. As domestic and international criticism of the SCAF escalated sharply with street protests on the first anniversary of the January 25 uprising, military officials attempted to distance themselves from the controversial investigation by pointing the finger at an independent judiciary operating beyond their control. On February 9, amid rapidly deteriorating relations with the United States, the SCAF issued a defensive statement denying culpability for the investigation and insisting that the NGO case was in the hands of the judiciary.

Egyptian Defense Attaché to the United States General Mohamed al-Keshki made the same argument, claiming that the military had no authority to intervene – even if it wanted to – in an investigation that was subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the judiciary and public prosecutor. By pinning the blame on a “bad cop” judiciary, the SCAF can watch the crackdown on NGOs unfold from a safe distance and pretend that it is powerless to stop it.

But the argument that interfering with an independent judicial investigation violates Egypt’s national sovereignty as well as the principles of democracy was a tune the Mubarak regime played frequently, and one that will be familiar to anyone who followed the politically motivated cases against civil society activist Saad Eddin Ibrahim between 2000 and 2003 and against presidential candidate Ayman Nour between 2005 and 2008. Ibrahim was charged with the explicitly political offense of “harming the reputation of the state” as well as of embezzlement, and Nour was charged with forging signatures on the application for registration of his political party. But it was crystal clear to any careful observer from the way the cases were conducted—the way state media were mobilized against the defendants, evidence was made public, and judges known to be close to the security apparatus were assigned—that they were 100 percent political in nature. All of those things are true of the anti-NGO cases now as well. And with the Ibrahim and Nour cases, Mubarak and all other Egyptian officials stoutly maintained that these were judicial matters and executive branch officials would not dream of interfering.

Nonetheless, at a certain point Mubarak decided that the costs of the Ibrahim and Nour cases had become too high and found a way to resolve them. In August 2002, after Ibrahim was sentenced to seven years in prison on appeal, President Bush informed Mubarak that he was rescinding an offer of $133 million in supplemental aid to Egypt in protest. Mubarak was furious and an anti-US campaign raged in the press for months. But in March 2003, Ibrahim’s case was referred to the Supreme Constitutional Court, which acquitted him of all charges after the briefest of hearings. Similarly with Nour, after years of tension with Bush over the case, Mubarak decided in January 2009 to resolve it in order to get relations with the new Obama administration off on a better footing. So Nour was released from prison on health grounds.

All of which goes to show that when the Egyptian government decides to resolve the NGO cases, it can and will do so. And it will most likely use the judiciary to resolve them, just as it used the judiciary to pursue them. Mubarak had a few people around who were smart enough to figure out how to do this; it is not clear so far whether the SCAF does, or whether all the smart people in the current government are on the wrong side of this issue.

Michele Dunne is the director of the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East. She can be reached at mdunne@acus.org.

Mara Revkin is the assistant director of the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East and editor of EgyptSource. She can be reached at mrevkin@acus.org.

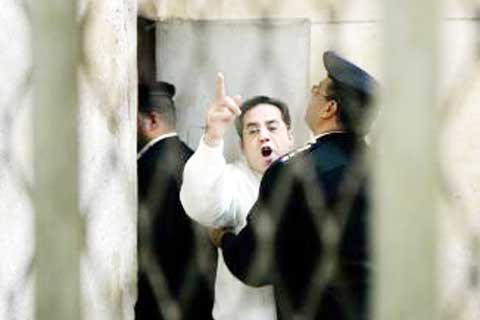

Photo Credit: The Daily News Egypt

Image: 63488.jpg