In mid-July of last year, in the affluent district of Heliopolis, a small group of citizens calling itself ‘The Silent Majority’ gathered to protest the protestors: “Tahrir doesn’t represent the Egyptian people – we have a range of opinions, and a host of demands far more significant than those belonging to the narrow interests of Midan Tahrir!” one woman fervently exclaimed. Such criticisms were to be expected at the time. Indeed, the question of who has the authority to speak on behalf of the popular uprising persists to the present day.

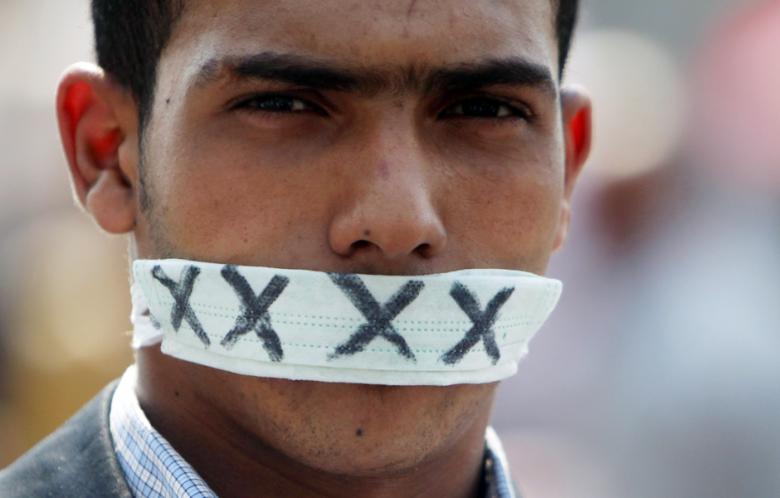

Also understandable was the urge, however misguided, to shoot the messenger. With Cairo’s nightly talk shows regularly giving voice to many disappointed with the speed or clarity of the country’s transition, the media opened themselves up to scapegoating by those supportive of the transition’s caretaker, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF). That day in July, Midan Roxy in Heliopolis featured posters of television personalities Reem Magid, Yusri Fuda, Wail al-Ibrashi, Ibrahim Isa, Bilal Fadl, Adil Hamuda, Hala Sarhan and others. Their faces were crossed out with red “X” marks and a caption below the images read “Spare Us Your Faces.”

Today, in light of an established record of SCAF antagonism to criticism, the practice of ‘concerned citizens’ blaming the media looks different. Two weeks ago, a group of some 700 petitioners calling themselves ‘Liberated Men, Women and Youth of an Honorable Egypt’ filed a complaint to the Prosecution General, charging twelve prominent activists, politicians and media figures (including Nawara Negm, George Ishaq, Asma’ Mahfouz, Wa’il Ghunim, Buthayna Kamil, Yusri Fuda and Reem Magid) with “smearing the reputation of the Armed Forces leadership, fomenting unrest and propagating hatred for the Egyptian army in the hearts of the youth through falsified information.” Insofar as their complaint deals with defamation of the military, legal code stipulates that the issue be passed to the military for ‘consideration.’ So while the spokesman for the Prosecution General was quick to seize upon this minor technical distinction to stress that the group of twelve had not officially been referred to a military court, the intent to intimidate through indirect means remains clear. Even the threat of military referral represents the continuation of a long legacy of tactics designed to intimidate regime opponents.

A quick scan of incidents in the last few months demonstrates this intent to stifle criticism:

After having abolished the Ministry of Information in March of 2011, the SCAF reinstated the agency in October and declared a suspension of issuing new licenses to television outlets and newspapers.

That same month, amid unclear circumstances, an episode of the talk show Akhir Kalam did not air. The program was set to examine recent comments by senior SCAF officials on the role of the military in the Maspero building confrontations – clashes which ultimately led to the death of 27 people, most of them Copts. The show’s presenter, Yusri Fuda, suspended his show in protest of what he described as “efforts to maintain the core of a regime which people went out in the streets to bring down.”

In late December, a contingent from the ‘Silent Majority’ turned up at the headquarters of the weekly newspaper Al-Fagr, threatening its editor, Adil Hamuda, with serious recriminations, including the destruction of his paper’s offices, should he continue to pursue an editorial line critical of the SCAF’s policies.

Incidents such as these led the media watchdog Reporters Without Borders to bestow Egypt with the dubious distinction in 2011 of the most dramatic decline in press freedom among Middle Eastern countries in its annual index. And should you question the agenda of a ‘foreign funded’ body like Reporters Sans Frontieres, one need go no further than Al-Misry al-Youm, Egypt’s widest-circulation, independent daily, where writers like Ala’ al-Aswani regularly chronicle the abuses of the military council. In one particularly comprehensive piece in December of last year, he describes the destruction of foreign correspondents’ equipment, the intimidation and forced confessions of local activists, trumped-up allegations against him and distortions in the state-controlled press, and summed it up bitterly, saying “It has now become clear that we have to feign blindness to satisfy the SCAF.”

This latest attempt to curb free speech is one element in a broader offensive on dissent that includes the ongoing campaign to vilify NGOs in state media and the recent acquittal of the army doctor who performed ‘virginity tests’ on female protestors. Remarkably, Egyptian journalists and activists have not yet been cowed, perhaps emboldened by the growing number willing to confront the military council. On the same day that the Prosecutor passed the citizens’ complaint to the military prosecution, a group of thirty prominent television personalities held a press conference announcing a new initiative to enhance journalistic standards, establish an independent television network and enshrine freedom of speech clauses in the new constitution. For those who support media freedom in Egypt, these journalists’ resilience provides a small measure of assurance in an otherwise bleak picture.

Kwame Lawson is a media analyst and former Managing Editor of the reform and democratization blog, Fikra Forum. He has a PhD in Arabic Literature from St. Andrews University.

Photo Credit: Akhbar

Image: Egypt_Censor_pic_4.jpg