President Mohamed Morsi’s recent constitutional declaration was a blow to the goals of the revolution; to achieve a real democratic transformation, to establish the rule of law, a separation of powers, and an independent judiciary. In effect, the president declared himself Pharaoh, putting himself above any challenge or opposition. Despite the decree extending the deadline fir Egypt’s draft constitution by two months, in yet another unexpected move, the Constituent Assembly took its final vote on the articles of the constitution, with only 85 members present, the vast majority of them Islamists.

Eleven members of the Constituent Assembly were replaced by alternates who were not given the opportunity to participate in previous discussions about the articles or the draft’s language. It seems that their only role was to contribute a vote of support for the drafted articles, and this is indeed what happened.

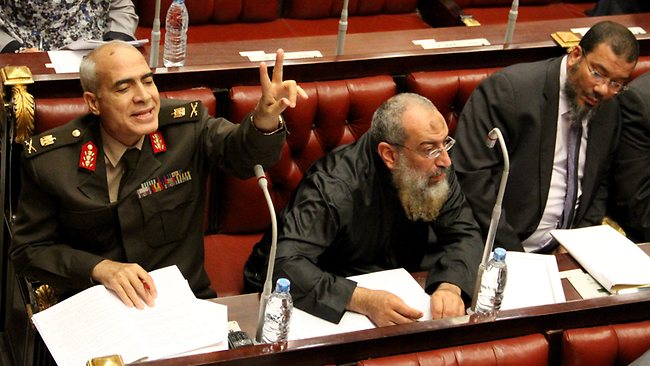

The assembly’s last session, continuing into the early morning hours on Friday, was completely void of any serious discussion on the articles of the constitution. The session ended with agreement on the draft, and Hossam al-Gheriani, the Assembly head, formally announced the result to the president on Saturday, who quickly called for a referendum on December 15.

There are no guarantees as to the integrity of a constitutional referendum since a large scale judges’ strike, mounted in opposition to the constitutional declaration, has disrupted the legal proceedings and judiciary logistics needed for a referendum.

The constituent assembly has engaged in a mix of political, legal, and administrative trickery that threatens the future of Egypt’s legitimacy. It ignored the fact that its own destiny is still subject to judicial ruling and continued its work moving the draft constitution toward public referendum even though the Supreme Constitutional Court has yet to rule on the legitimacy of its very existence. Apart from its legal standing, the assembly clearly lacks societal legitimacy. The political parties dominating the formation of the assembly have dealt with the constitution as though it is the private property of the dominant parties in the parliamentary elections. They ignored the fact that the composition of the assembly is not only a matter of political representation but, more importantly, a matter of true societal representation.

The draft constitution reveals a deep antagonism towards democracy and human rights. The assembly, for instance, has insisted on keeping al-Azhar in the place it held in the previous draft, requiring the consultation of a group of senior Islamic scholars in matters relating to Islamic law. This gives clergy the right to interfere in legislative affairs and the right to rule on whether laws passed by an elected parliament conform to the second article of the constitution which affirms that “the principles of Islamic law are the main source of legislation.” This is a clear offense to a modern democratic nation, and one which paves the way to the creation of a religious state.

For the first time in Egypt’s constitutional history, the constitution specifies a religious school of thought for the country and imposes loosely interpreted principles of Islamic law. This does nothing to help solve Egypt’s problematic relationship of religion and state but rather aggravates it. In the end, the rights of citizens and their basic freedoms become subject to the whims of the party that has a majority in parliament or maintains political control of Al-Azhar.

The constitution also opens the door to state interference in citizens’ private lives by granting the right to establish so-called “organizations for the promotion of virtue and prevention of vice.” It also refers to the role of the country and society in “preserving the authentic character of the Egyptian family, its cohesion and stability, and deepening and protecting its moral values, all as regulated by law.” It is unclear, however, how these ‘moral values and the character of the Egyptian family’ can be regulated by law. The constitution also mandates the state to protect societal values “as regulated by law.”

The draft’s hostility towards human rights goes so far as to fly in the face of international human rights agreements of which Egypt is a signatory. The 1971 constitution, on the other hand, stipulated the legal standing of these agreements and treaties. The new constitution restricts the freedom of religious practice to Muslims, Christians, and Jews. It also allows for access to and disclosure of personal information in the need of national security with only the loosest set of poorly defined restrictions such as not violating private life or the rights of others.

The desire to restrict freedom of the press is also abundantly clear. Press freedom is limited by what the constitution refers to as basic principles of the state and society and by the requirements of national security. The draft allows the legislature room to exploit loosely framed articles to curtail press freedoms. The constitution also allows for the closure or confiscation of media outlets by judicial order and allows for censorship of the press in wartime or when the armed forces have been mobilized.

The draft constitution also includes the creation of a National Media Council to regulate “issues of audio-visual broadcast, print and digital media, and others.” Among the primary objectives of this council will be the establishment of standards to which the press and media will be held in order to observe so-called “constructive social values and traditions.” The specific sections describing the council are vague, making further restriction of press and media freedom that much easier. The constitution makes no mention of how the council will be composed and how its members will be chosen, nor does it mention any of the necessary safeguards to ensure that it will be independent of executive authority.

While the constitutional assembly does grant the right to demonstrate, provided advance notice of the demonstration is given, it leaves the substance of regulation to legislators. As it happens, the Ministry of the Interior has drafted a bill that would regulate demonstrations, which can be described as nothing less than despotic, essentially intended to curtail the right to demonstrate. The constitution also provides for the right to form organizations – but it gives the courts the right to order their dissolution as regulated by law. Egyptian human rights organizations recently uncovered details about a new law, prepared by the current government, that would regulate organizational formation and they have described it as worse than any issued by Mubarak’s regime. As for the related issue of labor organizations, the constitution stipulates that “a profession shall establish no more than one professional syndicate” – a clear violation of the right to trade union pluralism.

At a time when the Islamist political parties are accusing the civil democratic leadership of a desire to return to military rule, the constituent assembly, most of its members Islamists themselves, undermined one of the revolution’s goals – ending civilian trials in military court. The constitution provides for the possibility of trying civilians in military courts, courts that are not independent bodies and do not provide necessary standards for a fair trial. The number of civilians referred to military courts under SCAF-led rule is believed to be over 12,000. Instead of putting an end to this practice, the constituent assembly granted constitutional legitimacy to a practice that is a gross violation of human rights.

Keen to take aim even at settled constitutional principles, the constitution includes the same text of the Political Isolation Law that the Supreme Constitutional Court declared unconstitutional. Article 232 calls for the “suspension of political rights of all leaders of the defunct National Democratic Party’s general secretariat, policy committee, political office, and its members in the People’s Assembly and Consultative Assembly who won office in 2005 and 2010.” Quite simply, this amounts to stripping a large number of citizens of their political rights without a verdict and without any specific crime being alleged.

The draft also stipulates that the practice of all the rights and freedoms found in the constitution may not violate the principles found in the section on state and society. Thus, the articles in that section are used to trump the right of individual citizens to practice their freedoms and human rights.

Finally, we can easily see that the Islamist parties’ insistence on taking an insular approach while calling it the “will of the majority” has resulted in a disfigured constitution after the revolution that is an affront to democracy.This constitution does not express the aspirations of the diverse Egyptian people but instead entrenches political and religious tyranny even more deeply, threatening the country’s stability. The assembly that drafted it lacks all political and societal legitimacy and its members are concerned only with advancing narrow political interests even if they conflict with the interest of the entire society and the goals of the revolution.

Ragab Saad is a researcher and Managing Editor of "Rowaq Arabi" Journal at the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS).

Photo Credit: AP

Image: CA%20.jpg