The first day of parliamentary elections dawned cool and rainy, but warmed up by 8 am, bringing out Egyptian voters whose sunny mood matched the mild Mediterranean weather and the cartloads of neon-bright oranges and guava that festooned the streets of Port Said on November 28. Campaign workers for various candidates and parties—especially Freedom and Justice, Nour, and the Free Egyptians—handed out leaflets to voters as they walked into polling places, heedless of legal restrictions on election day campaigning. Children ranging from preteens down to toddlers weaved their way among the crowds near polling stations, handing out small cards featuring the name, photo, and symbol of their candidate.

The cards were probably quite an effective method of campaigning, as many voters seemed bewildered by the ballots they received. First there was a small pinkish sheet showing all the party lists (13 here) from which the voter was to choose one; most voters I witnessed seemed able to do that.

|

| Poll workers in Port Said |

But the ballot for the individual seats, from which the voter was asked to choose two, was an enormous sheet of white paper covered with over 100 names accompanied by symbols. Many voters puzzled over the sheet for some time; one tiny elderly woman caused an entire voting station to break into giggles when she called in a loud voice from inside the voting booth: “I don’t get this! I can’t even see the name of the person I want to vote for! Someone has got to help me!”

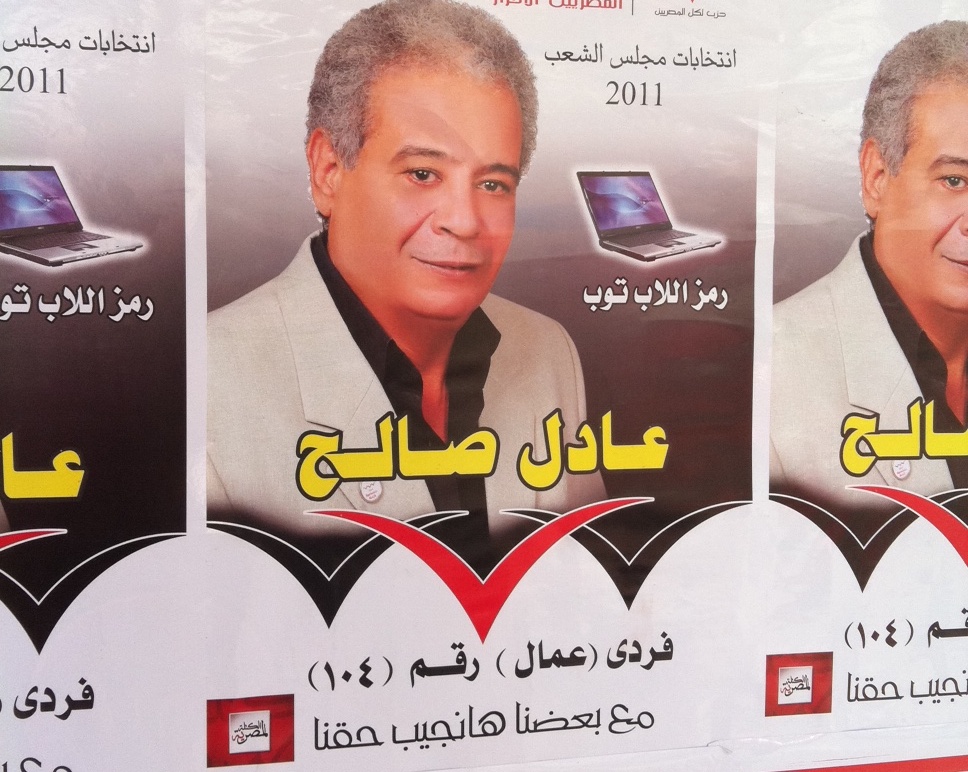

The candidate and party symbols themselves, meant to ease the voter’s predicament, are fascinating (there is definitely subject matter for a semiotics dissertation in this). The Free Egyptians have an eye; Freedom and Justice has scales (combined in the party’s logo with a bright, rising Islamic eight-pointed star); Nour has a Ramadan lantern; and the Wafd has a traditional palm tree. Individual candidates need to get more creative to distinguish themselves: a feather, a globe, a necktie, a tobacco pipe, a soccer goal, or (my personal favorite) a laptop.

The judicial officials who supervised the polls in Port Said appeared to be mostly in their 30s or early 40s, probably public prosecutors rather than actual judges, and some ran tighter ships than others. Some were extremely vigilant, even rather nervous, on their feet much of the time in order to see into every corner of the room and call out any violators of the rules, such as two people going into the voting booth together or agents advertising their candidate by wearing a large laminated photo or symbol around their necks.

|

| Party lists in a Port Said polling station |

Many Egyptians I encountered in a day of wearing my official mutaabi’ (observer) credentials were curious about our work and very welcoming, evincing pleasure in the international interest in their elections. A young man serving as a domestic observer for the Freedom and Justice Party approached me in a friendly manner, saying “I’m a member of the Muslim Brotherhood and when I tried to be an election monitor in 2005, I got thrown into jail. This time everything is different. The judge supervising this polling station is very fair and doing everything correctly. He even stops the voting for five minutes every few hours so that the observers can have a restroom break without missing anything. This is a dream come true for me.” A monitor from an Egyptian civil society organization agreed, saying, “We have real transparency for the first time ever in elections.” Then he smiled at me and added, “I guess you international observers would never have been invited if that hadn’t been the plan.”

But now begins a nervous night for those who want a fair and transparent election. Polls will be open until 9 pm (extended from 7 pm) tonight, at which point judges are to seal them and leave them under guard until reopening at 8 am tomorrow. With Egypt’s history of ballot-box stuffing and other forms of vote-tampering, this will be a nail-biter for many.

|

| A voter outreach campaign poster in Port Said advises voters: "Egypt is your home; care for it by voting just as you care for your home and family." |

Meanwhile, another form of ballot-box stuffing might turn out to be just as problematic. Each polling place (most of them school classrooms) I saw today had two sets of glass-sided wooden ballot boxes—one each to hold the pink (party list) slips and the white (individual candidate) slips. But those enormous white slips for the individual candidate seats, which need to be folded into quarters or sixths to be put through the slot, are filling up the boxes fast. Many boxes appeared to be nearly full as of late today.

Ballot boxes are not supposed to be unlocked until the counting begins some time after polls close on Tuesday night, but what if there is a strong turnout tomorrow and they fill up? Will voters and poll workers need to use superhuman strength to stuff more and more paper into the box? Will the judge open the box (a procedural no-no) to compress the ballots in order to fit more inside? Will new boxes appear? And whatever is done, will the whole process of transporting boxes, opening them, and tallying votes be open to domestic and international observers? The answers to those questions—as well as the continuation of the relative lack of violence of today–will determine in part whether the buoyant mood of November 28 soars or sours in the days ahead.

Michele Dunne is the director of the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East and an official observer of the first stage of the parliamentary elections. She can be reached at mdunne@acus.org.

Photo Credit: Michele Dunne

Image: port%20said-%20laptop.jpg