Factbox: The Syrian regime’s push in Idlib province

In recent weeks the Syrian conflict has escalated as the government seeks to retake control of Idlib province. This factbox aims to shed light on the latest developments, the humanitarian consequences, and the key actors involved. It follows a piece from December 2019 that looked at the Idlib crisis from a data analytics perspective.

What is going on in Idlib?

Since December 2019, the Syrian government has led an offensive on the northwestern Idlib province, which has intensified in recent weeks. Idlib is the largest area still outside of regime control and has tenaciously defied previous attempts to bring it to heel. It is also teeming with experienced rebel fighters, many of whom had been transferred there as part of negotiated surrender agreements after other rebel strongholds fell elsewhere in the country.

However, with much of the the rest of the country now back under control, the Syrian government has been able to turn its full attention to Idlib. In this effort, it is supported—as during its other offensives—by fearsome Russian airpower that demoralizes as much as it destroys, allegedly deliberately targeting civilian infrastructure such as hospitals to crush resistance. This pattern is so far repeating itself in Idlib, where dozens of hospitals have been bombed, many of which are completely destroyed.

As a result, rebel territory in the area is gradually being retaken by Syrian regime forces, taking a terrible toll on human life as the front-line advances.

The rebels are fiercely resisting. After being forced to retreat from the key town of Saraqeb on February 14, the rebels relinquished control to Bashar al-Assad’s forces of the strategic Aleppo-Damascus M5 motorway for the first time since 2012. On February 27, the rebels re-entered the town, handing the regime one of its first major setbacks since launching its latest offensive, but by March 2 government officials claimed the rebels had retreated once more.

At the same time, geopolitical consequences are mounting, with Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan saying that its own offensive in the area is only a “matter of time.” This follows the killing of thirteen Turkish troops in northern Syria in February as government forces pushed forward. In addition to a direct military incursion to bolster observation posts, Turkey is said to be providing artillery support to Syrian rebels, bringing Turkey and Russia ever closer to direct hostilities.

On February 27, at least thirty-three additional Turkish soldiers died in an attack by Syrian regime forces, with thirty more wounded. In response, Turkey claims that it struck two hundred Syrian government targets, “neutralizing” over three hundred Syrian troops. These latest developments are further raising fears that the conflict could descend into larger-scale confrontation between Russia and Turkey. Given Turkey’s membership of NATO, this could conceivably drag in other powers, including the United States. On February 28, NATO met at Turkey’s request to discuss the situation under Article IV, under which a signatory may request consultation if it is concerned for its territorial integrity, political independence, or security.

The geopolitical situation remains highly fluid. On March 1, Turkey announced a major offensive into Idlib and shot down two Syrian warplanes, but the following day agreed to talks in Moscow on March 5 aimed at achieving a ceasefire.

How did this offensive come about?

Idlib province was at the heart of a 2017 “de-escalation” agreement between Russia, Turkey, and Iran. It called for a six-month ceasefire in Idlib, as well as other key rebel strongholds in northern Homs, in the Damascus countryside, and along the border with Jordan. These other three areas have all since fallen to Syrian regime forces, in many cases with rebel troops and civilians transferred to Idlib and Aleppo as part of surrender deals. This fact makes the Idlib crisis all the more chilling. There is nowhere left to turn.

Despite Turkish and Russian troops monitoring the borders of the agreed de-escalation zone, the Syrian army proceeded to retake swathes of eastern Idlib over the winter during 2017 and 2018. After consolidating control in 2018 of other parts of Syria, the regime turned once more towards Idlib as the last major piece of contiguous territory still resisting. A 2018 buffer zone deal brokered between Russia and Turkey was never fully implemented, and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham’s (HTS) January 2019 takeover of much of Idlib made this a moot point. A limited offensive from April to August 2019 displaced four hundred thousand civilians but stopped after only slight territorial gains.

Since December 2019, the Assad regime has renewed its assault, bringing with it a terrible deterioration in conditions that UN humanitarian chief Mark Lowcock has described as the “the biggest humanitarian horror story of the 21st Century.”

What is the human cost?

Idlib province is at the epicenter of an acute refugee crisis on a massive scale. Northwest Syria was previously home to around one and a half million people. Now there are over four million civilians crammed into this corner of the country. As the fighting intensifies, more than 900,000 people have so far been displaced within Idlib, 80 percent of whom are women and children, many already displaced from elsewhere in the country.

Children alone make up 60 percent of the displaced. In other words, a heartrending 540,000 children are scrambling for shelter as the bombs fall around them. For comparison, this is equivalent to the entire city of Tucson, Arizona. Refugee camps are full and 170,000 displaced individuals are living out in the open. As a result, babies are freezing to death in the bitter winter, with temperatures dropping as low as 15 degrees Fahrenheit at night. According to UNICEF Executive Director Henrietta Fore, “Children and families are caught between the violence, the biting cold, the lack of food and the desperate living conditions.”

Almost six million civilians have already sought shelter in neighboring countries, with roughly two-thirds of those—an extraordinary four million refugees—going to Turkey. However, Turkish authorities have said that they have already reached their limit. With the government’s noose tightening around Idlib, these refugees are trapped. They have been massing on the Turkish border as their last hope of escaping the retribution of a regime that sees these most stubborn of rebels as terrorists and traitors.

With the migration pressure building on the frontier with Syria, Turkey has sought to relieve it elsewhere, opening up its border with Greece and Bulgaria to migrants seeking to move into Europe. This goes against the terms of a 2016 deal which saw Turkey close its European borders to migrants, in exchange for aid from the European Union. Depending on the size and duration of this latest flow of refugees, it could spark another migration crisis akin to that seen in 2015, when over one million migrants arrived on Europe’s shores.

By the morning of March 1, Turkey claimed that 76,000 migrants had already crossed, with the United Nations putting the number much lower, at 13,000, not all of whom had attempted a crossing. Even so, at least 1,200 migrants had arrived on the Greek island of Lesbos by March 2.

Who is involved on both sides?

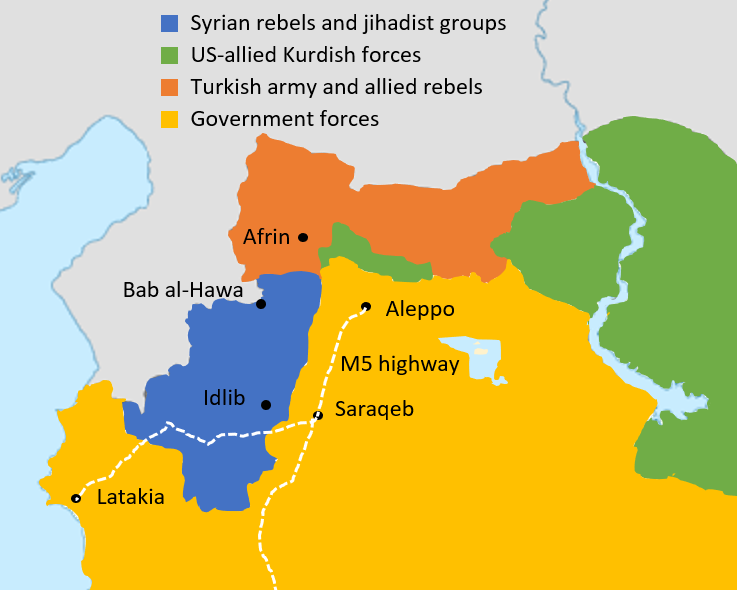

The Syrian conflict is the stage for an acronym soup of different actors, each oftentimes supported by an array of state and non-state backers. Broadly speaking, the four groups are: the Syrian government, Syrian rebels and jihadist groups, Turkish army forces and allied rebels, and Kurdish forces, who are allied to the United States. However, these buckets mask significant fragmentation within each category, especially within the rebel and jihadist umbrella, home to a cornucopia of different factions that are often at odds with one another.

Syrian regime forces are led by President Assad, against whom the people rose up at the start of the Arab Spring in 2011. Alongside domestic loyalist troops, this faction is bolstered by support from Iran and Hezbollah, its militia ally based in Lebanon, as well as Russian forces and mercenaries. Iran’s intervention–orchestrated by the late Major General Qasem Soleimani–was critical in the staving of regime collapse during the early days of the civil war. This involved deployment of both Iranian troops from the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corp’s (IRGC) foreign wing, the Quds Force, as well as up to 80,000 Iran-affiliated Iraqi and other foreign militias to bolster Assad’s flagging army. However, it is Russian air support that turned the tide since 2015 and has mercilessly borne down on Idlib in recent days.

The Syrian rebels and jihadist groups have been at best uneasy bedfellows and more commonly fierce rivals in the confined territory of Idlib. Each faction has jostled for power and influence, often bankrolled by outside powers such as the United States, as well as wealthy Gulf states like Qatar and Saudi Arabia. However, much of this support dried up in 2017 as foreign governments saw the writing on the wall. Over time, groups considered more moderate, such as the Free Syrian Army (FSA), have gradually been marginalized. More violent and radical groups have taken their place.

Following a bloody takeover in January 2019, a jihadist alliance known as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) assumed control over most of Idlib, with only occasional pockets being run by splinters of other groups. HTS originated from the al-Qaeda-affiliated al-Nusra front, who claimed in 2016 to have severed ties to al-Qaeda. Following a subsequent rebrand and several mergers, HTS emerged. As the noose has tightened around Idlib, HTS is said to have moderated their extremist rhetoric and behavior, though this decision may have been born of necessity, not conviction, as their ranks are thinned through conflict. At the same time, they have been reinforced by foreign jihadists such as Uighurs from China’s restive Xinjiang province and other central Asian countries. Those who consider that HTS has become too moderate split off in 2018 to form Hurras al-Din, now considered al-Qaeda’s new affiliate.

Most former fighters of the FSA and other moderate groups who did not join HTS were folded into the National Front for Liberation, which in turn merged with the Syrian National Army (SNA), also known as Turkish-backed Free Syrian Army (TSFA). These entities represent a catch-all alliance home to hardline Islamists as well as secular rebels. They are supported by Turkey, who controls significant parts of northern Syria following incursions over the border in early 2018 and late 2019 to drive Kurdish forces out of the border region.

Syrian Kurds and their allies are the other significant faction in northern Syria, although they are not in Idlib province. Under the umbrella of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) sit the mostly Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG). Turkey sees Syrian Kurdish forces as linked to the Kurdish Worker’s Party (PKK), which Turkey considers to be a terrorist organization. SDF and YPG forces were central to multilateral efforts to combat the spread of the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) in Syria and Iraq and are considered a close ally of the United States. However, President Donald Trump ordered US troops to step aside when Turkey decided to launch its attack on the Kurds, prompting claims of betrayal.

Reliable figures for these groups are hard to come by. Various sources put the combined number of anti-regime forces at anywhere from forty to seventy thousand. The United Nations considers that HTS fighters total between ten and twelve thousand, with a further five thousand affiliated with Hurras al-Din. The US Department of Defense reckons Turkish-backed militias across northern Syria number from twenty-two thousand to fifty thousand. The Royal United Services Institute in the United Kingdom believes foreign jihadists number several thousand.

If Idlib falls, the fate—and final destination—of these fighters is far from clear.

Kyle Thetford is an intern with the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs. Follow him on Twitter @thetfordk.

Image: Internally displaced Syrians are seen in an IDP camp located in Idlib, Syria February 27, 2020 (Reuters)