Civil society organizations and nongovernmental organization (NGOs) in Egypt are in a crisis. In late June, the Ministry of Solidarity presented a restrictive new NGO draft law that would severely restrict the formation, activities, and funding of NGOs. Egypt’s repressive climate for NGOs, however, is not new. In December 2011, the Egyptian authorities, objecting to foreign (mainly US) funding of international democracy NGOs operating in Egypt, raided 10 NGO offices, including four American organizations: Freedom House, the International Republican Institute (IRI), the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ), and the National Democratic Institute (NDI). In February 2012, the Egyptian prosecutor general indicted 43 employees of these organizations and a German organization on charges of operating without a license and receiving illegal foreign funds. In June 2013, a Cairo criminal court convicted all 43 defendants to prison terms in what observers, including the US and European governments, said was a deeply flawed trial. In response to the verdict, Secretary of State John Kerry said, “The United States is deeply concerned by the guilty verdicts and sentences, including the suspended sentences, handed down by an Egyptian court today against 43 NGO representatives in what was a politically-motivated trial.” The White House echoed Kerry’s statement, while European Union High Representative Catherine Ashton and Commissioner Štefan Füle expressed “concern” over the verdicts. German Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle stated, “We are outraged and highly disturbed by the harsh sentences imposed on employees of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung in Cairo,” and European Parliament President Martin Schulz called the conviction “unacceptable, unjustified and intended to strangle a vivid civil society in Egypt.” Meanwhile, Human Rights Watch described the verdicts as “unjust convictions based on an unjust law.” In addition to the prison terms handed down to the 43 defendants, the Egyptian offices of the NGOs were shut down.

Civil society organizations and nongovernmental organization (NGOs) in Egypt are in a crisis. In late June, the Ministry of Solidarity presented a restrictive new NGO draft law that would severely restrict the formation, activities, and funding of NGOs. Egypt’s repressive climate for NGOs, however, is not new. In December 2011, the Egyptian authorities, objecting to foreign (mainly US) funding of international democracy NGOs operating in Egypt, raided 10 NGO offices, including four American organizations: Freedom House, the International Republican Institute (IRI), the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ), and the National Democratic Institute (NDI). In February 2012, the Egyptian prosecutor general indicted 43 employees of these organizations and a German organization on charges of operating without a license and receiving illegal foreign funds. In June 2013, a Cairo criminal court convicted all 43 defendants to prison terms in what observers, including the US and European governments, said was a deeply flawed trial. In response to the verdict, Secretary of State John Kerry said, “The United States is deeply concerned by the guilty verdicts and sentences, including the suspended sentences, handed down by an Egyptian court today against 43 NGO representatives in what was a politically-motivated trial.” The White House echoed Kerry’s statement, while European Union High Representative Catherine Ashton and Commissioner Štefan Füle expressed “concern” over the verdicts. German Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle stated, “We are outraged and highly disturbed by the harsh sentences imposed on employees of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung in Cairo,” and European Parliament President Martin Schulz called the conviction “unacceptable, unjustified and intended to strangle a vivid civil society in Egypt.” Meanwhile, Human Rights Watch described the verdicts as “unjust convictions based on an unjust law.” In addition to the prison terms handed down to the 43 defendants, the Egyptian offices of the NGOs were shut down.

Consequently, the House Foreign Affairs Committee’s (HFAC) Subcommittee on the Middle East and North Africa requested that the Government Accountability Office (GAO) “examine the ability of the US government and its implementing partners to operate in Egypt after the convictions and the effect the trial had on US efforts to promote democracy and governance in Egypt.” The focus of the GAO’s subsequent report, entitled Democracy Assistance: Lessons Learned from Egypt Should Inform Future US Plans, was threefold. First, it examined the extent to which the US government identified the risks of providing democracy and governance assistance in Egypt. Second, it examined what support the US government provided to the NGOs prosecuted by the Egyptian government. Lastly, it looked at how the 2013 prosecution has affected US democracy and governance assistance in Egypt.

On July 24, 2014, the findings of the GAO report were presented to the Subcommittee in a hearing entitled “The Struggle for Civil Society in Egypt.” In the first panel, Charles Michael Johnson, Jr of the GAO delivered a summary of the report. In the second panel, four of the convicted NGO workers testified about how the trial affected their lives and civil society in Egypt. The witnesses were Charles Dunne, Director of Middle East and North Africa programs at Freedom House, Sam LaHood, former Egypt Country Director at IRI, Patrick Butler, Vice President of programs at ICFJ, and Lila Jaafar, senior program manager at NDI.

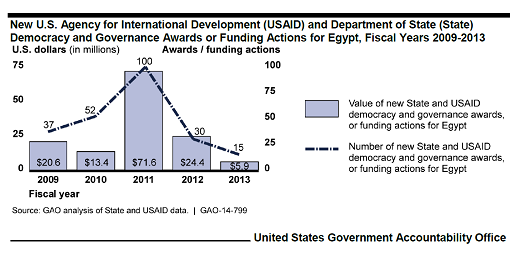

In his testimony, Johnson noted that the NGO case led to a significant reduction in US funding for democracy and governance assistance in Egypt. From 2010 to 2011, US funding awarded in Egypt increased from $13 million to $72 million. This came after Egypt’s January 2011 revolution and included an increase in direct funding to NGOs totaling about $65 million (including to the four prosecuted US NGOs). By 2013, funding had dropped to about $6 million. In addition, the GAO reported that the number of grants awarded for new democracy and governance projects also decreased from 100 in 2011 to fifteen in 2013.

The GAO report’s main finding was that since the 2013 conviction, the US State Department (DOS) and US Agency for International Development (USAID) have not “documented lessons learned from the US experience in Egypt and have not incorporated these lessons into their future plans for democracy and governance assistance.” Johnson reported that DOS and USAID both concurred with this recommendation. Johnson, however, stated that in conducting research for the report, his team faced burdensome and unnecessary procedures in acquiring needed documents from DOS and USAID.

In his testimony, Johnson asserted that, “Consistent with State and USAID policies and internal control standards, the US government identified potential risks in providing democracy and governance assistance in Egypt dating back to 2005.” He cited the US government’s awareness of the Egyptian government’s “likely objection to the US plan to use $65 million to directly fund NGOs shortly after the revolution in 2011” and pointed to a cable issued in 2013 by DOS and USAID that contained guidance on how to counter increasing risks to NGOs globally, as examples of steps taken to manage the risks of providing democracy and governance assistance in Egypt.

Congressman Ted Deutch (D-FL) asked Johnson whether DOS and USAID have the ability to handle the risks associated with providing democracy and governance assistance in Egypt. Johnson answered affirmatively, but added that it is important for DOS and USAID to apply lessons learned from Egypt in order to mitigate and plan for future risks. In response to similar questions from Congressman Gerry Connolly (D-VA) and Congressman David Cicilline (D-RI), Johnson continued to give DOS and USAID credit for identifying and taking steps to mitigate risks as early as 2005. Johnson declined to offer recommendations for policy changes regarding risk management, stating that policy recommendations were not under the purview of the GAO. While Johnson declined to offer policy recommendations, he did offer some specific lessons to be taken away from the GAO report after being pressed by Congressman Cicilline. For example, he stated that NGOs should be aware of activities to which host countries are likely to object, and that such activities should be documented. Johnson added that an alternative approach for moving forward with democracy and governance assistance would be to support NGOs other than those that were prosecuted. However, Congressman Deutch objected to this recommendation, commenting that the goal should be to avoid prosecution by the Egyptian government in the first place, not to work around it.

The testimonies of the four convicted NGO workers provided a counterbalance to the somewhat uncritical findings of the GAO report. In his testimony, Dunne explained that the conviction was especially damaging for several Freedom House’s employees who were forced to flee Egypt for fear of being imprisoned. He explained that those employees, who are not American and have or are currently seeking political asylum, “have five young children among them, effectively exiling them from their parents, who are not free to go back home to see their families.”

Butler also offered a more detailed account of the destructive effect of the whole episode. He explained that for him, the conviction has been an “inconvenience.” However, his colleague Yehia Ghanem, an Egyptian journalist and editor with nearly 30 years of experience, is now in the United States and has been separated from his wife, three children, and ailing mother, for over a year. If he returns to Egypt, he will be jailed, and he has lost his career in Egypt and his pension. His family in Cairo has suffered continued harassment from the Egyptian authorities. Security forces have conducted three raids on their home, including one just last week.

LaHood described the challenges he has experienced as one of the NGO staff who was “entangled in an intergovernmental dispute between the United States and Egypt.” He explained that it is unclear whether his conviction as a felon in Egypt applies in the United States. He testified that his conviction has complicated applications for loans, jobs, visas, and life insurance. In addition, his voting status in Virginia remains unclear, because the state’s voting law is vague and stipulates that convicted felons can only vote once they have completed their sentences. His ability to travel has also been severely curtailed due to the fear of being extradited to Egypt by other countries. In an op-ed in the Washington Post published the day of the hearing, LaHood wrote that “a year later, the full implications of my conviction are still emerging.”

The testimonies suggested several steps the US government should take to support the convicted NGO workers. The GAO report stated that the US government “provided the four prosecuted US NGOs with diplomatic, legal, financial, and grant flexibility support.” The witnesses, however, called on the United States to do more. LaHood explained that Congress, by statutorily affirming that the convictions were politically motivated and are not recognized under US law, has the ability to “remove the legal question mark” over the heads of those convicted and end the “frustration of trying to determine, under 50 separate State jurisdictions, whether the convictions affect our ability to conduct routine everyday business.” Dunne and LaHood also urged the United States to press the Egyptian government to pardon the convicted NGO workers. Dunne explained that he had not been given a point of contact at DOS for information about US efforts in the case, and that after a year it feels as if DOS has moved on. Butler also echoed the need for a point person at DOS. Congressman Deutch expressed confidence that following the hearing it would be easier for the convicted NGO workers to identify such a point of contact.

The testimonies also suggested that the US hasn’t done enough to keep supporting NGOs after the conviction, and those testifying all called on the US to do more to support democratic activists and NGOs working towards reform in Egypt. In her testimony, Jaafar asserted that “Democratic activists in Egypt do exist and they have every intention of working for genuine political reform. They deserve international support.” She explained that many civil society organizations in Egypt that had worked with Freedom House, IRI, ICFJ, and NDI feel abandoned as they continue to work towards reform despite increased repression. LaHood urged the US not to downgrade its support of civil society organizations in the region. Dunne called on the US to “use the megaphone of the presidency and the State Department to call out human rights abuses, so as to encourage our friends in civil society and, most important, to let Egyptians know they are not forgotten and abandoned in their fight for freedom.” Moreover, he argued that the US must “reevaluate the basis of the relationship [with Egypt], including military aid, and consider shifting most if not all aid to economic support and educational programs, which will actually help the Egyptian people. “

The testimonies also offered insight into the current climate in for NGOs in Egypt, an assessment that was absent from the GAO report. Specifically, the testimonies called attention to Egypt’s recent NGO draft law, put forward by the Ministry of Social Solidarity in late June, and drew connections between the law and the 2013 NGO convictions. Both Butler and Jaafar reflected that NGO prosecution and trial was a “canary in a coalmine- a warning of even worse things to come.” The draft law is even restrictive than the law under which Jaafar and her colleagues were convicted. She explained that under the draft law, “International NGOs like ours would still be subject to the prior approval of multiple government ministries, including the state security apparatus, before registration is granted, and even afterward be subject to constant monitoring and vulnerable to charges of violating the law due to the overly broad language included in the draft.” She continued, “Our verdict, the raids on NGOs, the trials of journalists, the protest law and the proposed NGO law…directly contradict the promises of freedom of expression and association, and a free press guaranteed in the 2014 Egyptian Constitution.”

Dunne argued that the draft law seems aimed at preventing NGOs from conducting democracy promotion activities. He stated, “All in all, the draft law would take control of the NGO sector in a way that violates the norms of democracy, US interest in a politically stable and free Egypt, and Egypt’s own commitments under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which it is a State party.” LaHood commented that if the NGO draft law is approved, it will “deal a serious blow” to the Egyptian NGO community and subordinate such organizations to the control of Egypt’s security establishment. Butler placed the current draft law in perspective with the 2013 conviction, and added, “Everything the Egyptian leadership is now doing to intimidate the country into acquiescence could have been foretold by the verdicts last year against the NGO workers.”