How the US military should leave Iraq

A withdrawal of most US military forces from Iraq seems likely this year as the Iraqi government seeks to maintain some sort of diplomatic and economic relationship with the United States without alienating its powerful neighbor Iran. How this withdrawal is managed will help determine future US influence not only in Iraq but in the Middle East as a whole.

Iranian support for Prime Minister-designate Mustafa al-Kadhimi—who has had good relations with the United States—appears to be predicated on his agreeing to negotiate a new Status of Forces agreement (SFA) with Washington, which aims to remove the bulk of the several thousand US troops still deployed in Iraq.

The Americans’ mission was ostensibly to prevent the resurgence of the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) and to train Iraqi armed forces. However, the US jeopardized their continued presence in the country by breaching the terms of a 2008 SFA; they targeted Iran-backed Shia militias and the leader of Iran’s Quds Force, Qasem Soleimani, on Iraqi soil after a spate of attacks on American military and diplomatic targets last year. Even if the US actions were justified both to defend Americans and to deter future attacks, they represented a significant escalation in the rules of the game—an unprecedented targeting of a senior Iranian official in a foreign country.

The attack near Baghdad, when Soleimani was on an official visit, put Iraq in an untenable position. Iraq cannot afford to alienate a powerful neighbor with which it shares a 1,400-kilometer border and which has deep relations with a variety of Iraqi armed groups. If forced to choose, Baghdad will choose Iran, not the United States. It is, therefore, not in US interests to force Iraq to make such a choice.

While Tehran has long sought an exit of US forces from Iraq, Iran-backed militias did not attack US forces in Iraq while the US remained in compliance with the 2015 nuclear deal. The situation deteriorated after the US withdrew unilaterally from that deal in 2018 and sought to put a total embargo on Iran’s oil exports in 2019. That was when Iran commenced a series of retaliatory actions in the Persian Gulf and Iraq that prompted the assassination of Soleimani in early 2020. Also killed by the drone strike near Baghdad airport, were several Iraqis, including Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, the leader of the Kataib Hezbollah militia and deputy commander of all of the Popular Mobilization Forces that had battled ISIS. The assassinations led the Iraqi parliament to pass a non-binding resolution expelling American forces.

Tensions abated somewhat after Tehran accidentally shot down a Ukrainian civilian airliner on January 8, mistaking it for a hostile US missile. The outbreak of the coronavirus in Iran and its neighbors also took attention away from US-Iran strains. However, a second spate of tit-for-tat attacks occurred in March, leading to the death of two more Americans and a British citizen, as well as three Iraqi soldiers, an Iraqi civilian, and several militia members. US forces have now been withdrawn from three isolated outposts in Iraq and consolidated in the relatively safe Kurdish city of Erbil and at the al-Assad air base outside Baghdad. The United States also brought in Patriot missile batteries to defend these bases against militia rockets.

This author has argued elsewhere that the decision to kill Soleimani and Muhandis was an overreaction to Iranian provocations that would make a long-term US military presence in Iraq very difficult—if not untenable. That the crisis came at a time when Iraqis had been protesting in the streets against Iran’s excessive influence in their country made assassination even more strategically questionable. Overnight, the issue became the United States, not Iran.

However, it is still possible to retain US influence in Iraq and to offer Iraqis an alternative to complete domination by Iran. This goal would be advanced by an effort to de-escalate tensions with Tehran; at a minimum, to deal with any provocation by Iran-backed groups in a way that does not humiliate Iraqi politicians by violating their country’s sovereignty.

Ideally, the United States should re-examine its policy of “maximum pressure” toward Iran, which has not and will not achieve its stated goals. Iran is more, not less, aggressive in the region, continuing its development of ballistic missiles—including its first successful satellite launch—and has accelerated its nuclear program. More pressure will either lead to war, strengthen Iranian hardliners, or both. Even a botched initial response to the coronavirus does not appear to have increased the chances for regime change. If anything, these crises have increased the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps’ economic and political dominance.

The United States could use the pandemic as an opportunity to make goodwill gestures toward Iran. While the Iranian government has rebuffed such offers, they resonate with the Iranian people, whose views of America and its citizens have historically been much more positive. The neutral US reaction to the first transaction by INSTEX was a good first step and further guidance from OFAC facilitating the supply of medicine and medical devices to Tehran was welcome. Iran should, also, be allowed to receive the emergency loan it requested from the International Monetary Fund and have access to revenue frozen in foreign banks for medical supplies.

However, even in the absence of any real improvement in US-Iran ties, it should still be possible to remove Iraq from the middle of hostilities. This will oblige the United States to significantly reduce its forces in Iraq and restrict the remaining troops’ role to training and counter-ISIS operations. Iran, in turn, should restrain its Iraqi proxies from attacking US targets and give Kadhimi a solid chance to stand up a new government.

Since 2003, little has happened in Iraqi politics without Iran playing a role, which is predictable, given Iran’s long association with the Iraqi Shia and Kurds that opposed the rule of Saddam Hussein. The US lost opportunities to cooperate with or, at least, avoid antagonizing Iran, swayed by those in the administration who hubristically believed that they could instigate regime change in Tehran. Other mistakes—such as dissolving the Iraqi army, failing to protect Iraqi infrastructure from looting, and installing a Lebanon-like system in Iraq, with top positions for ethno-religious factions—doomed the country to sectarian strife and increased Iran’s ability to manipulate political developments. Nevertheless, as memories of the 2003 invasion fade, young Iraqis are more focused on constructing a less sectarian society that delivers jobs and other tangible economic benefits. They resent Iran’s meddling and want to reconnect with the Arab world and beyond.

The United States can support this trend by keeping Iraq out of its fight with Iran to make it easier for Iraqi politicians, businesspeople, and security officials to maintain some sort of constructive relationship with Americans. US intervention in Iraq has cost thousands of American and tens of thousands of Iraqi lives as well as billions in US taxpayer funds. For those who died and sacrificed on all sides since the invasion, the United States should find a way to withdraw most of its military forces with dignity. Otherwise, US credibility and influence throughout the region will fade to the benefit of Iran, China, Russia and ISIS.

Barbara Slavin is director of the Future of Iran Initiative at the Atlantic Council. Follow her on Twitter: @barbaraslavin1.

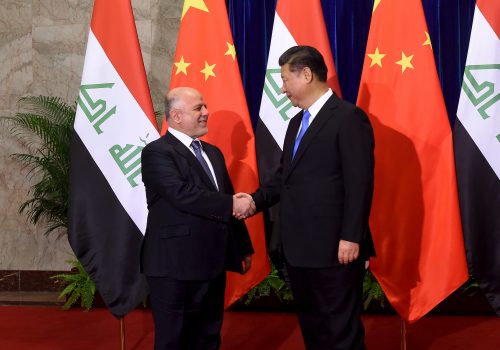

Image: U.S. Lieutenant Colonel Jace Neuenschwander, a battalion commander in Task Force Nineveh, shakes hands with Iraqi General Mohammed Fadel, who wears a face mask and gloves, following the outbreak of coronavirus disease (COVID-19), during a handover ceremony of U.S.-led coalition forces to Iraqi Security Forces as part of a drawdown of coalition troops at the Nineveh presidential palace, in Nineveh, Iraq March 30, 2020 (Reuters)