I’m the former foreign minister of Yemen. My country is starving and needs the international community’s help.

The Saudi-led coalition’s operations in Yemen to defeat the pro-Iranian Houthis and restore the internationally-recognized government of Yemen (IRG) are set to end their seventh year on March 26, with no signs of a political settlement. The protracted conflict and the economic collapse it has caused have pushed the country into the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.

According to various United Nations (UN) agencies, 20.7 million Yemenis—two-thirds of the total population—require humanitarian assistance—12.1 million of which face acute need. Many of those in dire need of aid belong to the country’s four million internally displaced persons (IDP). Yemen has become increasingly food insecure, with five million people facing emergency conditions and nearly fifty thousand facing full-blown famine. A 2021 UN Development Programme report stated that 377,000 Yemenis will have perished due to the war by the end of the year, nearly 60 percent of whom died from the war’s impact on access to food, water, and health care.

Causes of the crisis

Actors on all sides have contributed to Yemen’s descent into crisis. The Houthis have regularly looted UN convoys carrying humanitarian relief and food aid is often sold in marketplaces for profit. The Saudi-led coalition’s blockade of the al-Hudaydah Port on the Red Sea and Sana’a International Airport in the capital have restricted vital channels for aid delivery. While Saudi Arabia has expressed its willingness to negotiate the reopening of these channels, the Houthis have insisted that the reopening is a prerequisite for negotiation, not an issue open for discussion.

In IRG-controlled territory in the country’s south and east, poor economic governance has triggered rapid currency depreciation and exacerbated the humanitarian crisis. Since early 2020, the Yemeni rial has lost nearly half its value, with the black market exchange rate for one US dollar dropping from 600 to 1,650 rials in some areas. The collapse of the local currency has drastically weakened Yemenis’ ability to purchase imported food products, which comprise 90 percent of Yemen’s basic commodities. Alongside monetary issues, the government’s insolvency has prompted delays in public sector salary payments, and funding for service programs has dwindled.

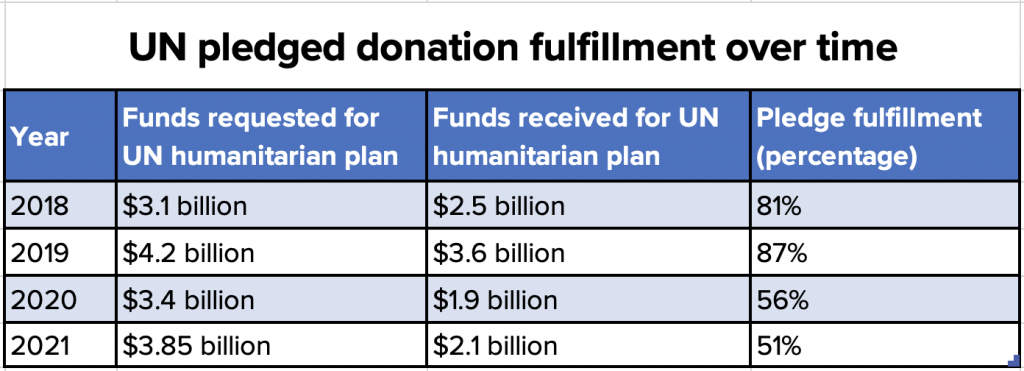

To make matters worse, the economic collapse has coincided with waning international support for humanitarian operations in Yemen. Donors to the UN-coordinated humanitarian response plan have fulfilled less and less of their pledged donations. Moreover, Saudi Arabia, which previously provided the IRG with crucial infusions of foreign capital to finance daily operations, appears increasingly reticent to donate additional funds due to rampant corruption within the internationally-recognized government.

The ongoing Houthi offensive on Ma’rib, the IRG’s last remaining city in the historical north, has added an extreme sense of urgency to the need to revamp humanitarian operations in Yemen. Ma’rib governorate now hosts a one million-strong IDP community, most of whom fled from other northern governorates when conflict erupted in 2014. The Houthis’ campaign to take the city has subjected them to front-line fighting, mortar strikes, and rocket attacks, and many camps have lost access to basic services as a result.

Options for the United Nations

Despite these realities, there remain options the UN can take to prevent the further collapse of the economy, stave off the onset of famine, and alleviate suffering in Yemen. First, the Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary General for Yemen should lead international efforts to stabilize the Yemeni rial and address the issue of public sector payments.

The UN-brokered Stockholm Agreement of 2018 previously established a joint account to finance civil servant payments in both IRG and Houthi territory using funds collected from taxes and duties paid at al-Hudaydah Port. While the account at the port fell victim to predation by the Houthis due to poor UN oversight measures, the concept of a joint account is still valid. During informal negotiations in Jordan in late 2018, the governor of the IRG-controlled Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) developed a plan to hold these funds in a Jordanian account. Reviving this idea will provide a new mechanism for delivering funds to civil servants across the country.

The international community, particularly the five permanent members of the UN Security Council (UNSC), should encourage the IMF to work with the IRG and Houthi authorities in Sana’a to formulate a joint response to the collapse of the monetary system. This should begin with forming an emergency panel of economic experts that includes officials from the two warring branches of the Central Bank of Yemen based in Aden and Sana’a to coordinate monetary policies. These cooperative measures may also aid in securing a new source of international funding as potential donors see greater potential for economic recovery.

The IMF’s endeavors should run parallel to a new set of World Bank projects designed to boost agricultural production, provide temporary cash for workers, rehabilitate service provisions in communities, and support fishermen. Some Gulf Cooperation Council countries have already established small projects in southern Hadramawt and Ta’izz governorates, which can serve as a blueprint for a more comprehensive economic response plan. These must be conducted through non-UN entities, as the United Nations considers these projects outside its mandate.

Instead, the UN can contribute to international efforts by developing a complementary humanitarian response plan that relies heavily on engagement with local civil society organizations. These relationships with Yemeni civil society organizations will allow the UN to identify communities of acute need—such as women, persons with disabilities, or other marginalized groups—and develop systems to provide them with additional social protections. They will also allow for more localized approaches to conflict management and economic recovery.

Finally, the UN must also rethink its engagement with various parties to the Yemeni conflict. While all permanent UNSC members have expressed their support for a unified Yemen, they have failed to coordinate their outreach efforts in a meaningful way. Together, the UNSC members can adopt a more aggressive diplomatic campaign that will more quickly and effectively bring together representatives from across Yemen’s political spectrum and geographical divides.

These countries, alongside the Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary General for Yemen, can then build on this cooperation to establish an international political conference on Yemen. This forum will not only place pressure on Iran to come to the negotiating table, but will also push the IRG’s nominal allies to address the crippling issue of corruption within state institutions.

The situation in Yemen cannot be permitted to continue on its current trajectory. Every day, purchasing power drops, services deteriorate further, and ordinary Yemenis sink further into crisis. The international community must act immediately to remedy these issues and change the country’s course from disaster to diplomacy.

Ambassador Khaled H. Alyemany is the former Foreign Minister of Yemen.

Further reading

Fri, Feb 12, 2021

A historic opportunity for peace in Yemen

MENASource By Nabeel Khoury

There is a hard and complex road ahead, but the Biden administration has taken a major first step in the right direction.

Tue, May 5, 2020

Aid groups desperately look for other options to combat coronavirus

MENASource By Borzou Daragahi

The pandemic has prompted organizations to reconfigure the way they provide aid.

Tue, Feb 23, 2021

Optimism mixed with realism about the Biden administration’s promises on Yemen

MENASource By Khaled H. Alyemany

The appointment of Ambassador Tim Lenderking as US Special Envoy to Yemen is the right step towards streamlining United States’ efforts internally and externally with allies to end the war, address its humanitarian impact, and avert the looming famine.

Image: Afaf Hussein, 10, who is malnourished, sits outside her family house in the village of al-Jaraib, in the northwestern province of Hajjah, Yemen, February 17, 2019. REUTERS/Khaled Abdullah