The Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) intervention in Syria’s war changed the outcome of the war and has, at least in the short term, secured the Assad regime in the face of a popular revolution and armed rebellion. The war is also changing the IRGC. Previously tasked with protecting Iran from a foreign invasion and countering internal threats to the regime in Tehran, it is quickly transforming into an expeditionary force.

The Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) intervention in Syria’s war changed the outcome of the war and has, at least in the short term, secured the Assad regime in the face of a popular revolution and armed rebellion. The war is also changing the IRGC. Previously tasked with protecting Iran from a foreign invasion and countering internal threats to the regime in Tehran, it is quickly transforming into an expeditionary force.

A survey of Persian language media coverage of funeral services held in Iran for Iranian nationals killed in combat in Syria, provides some indication of the IRGC’s transformational change: ever since the killing of Major Moharram Tork in Damascus on January 19, 2012, a total 476 Iranian nationals were killed in combat in Syria. The latest Iranian combat fatality registered at the time of the writing of this article was the March 26th funeral service of Hossein Gholami Moez.

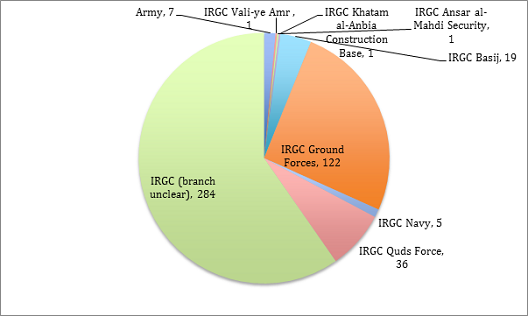

Further investigation into the service affiliation of the fatalities shows only 7 served in the Islamic Republic of Iran Army, and the rest in the IRGC. Ever since the 1979 revolution and establishment of the Islamic Republic, a dual military system is in place with the Iranian army constitutionally mandated with safeguarding the territorial integrity of Iran, and the Revolutionary Guards preserving the revolutionary nature of the regime. The IRGC’s constitutional mandate includes the concept of “export of the revolution,” which is a source of prestige and finance to the Guards.

This explains why there are so few army fatalities in Syria: in spite of repeated army leadership declarations of readiness to play a more active role Syria, the war fell into the Revolutionary Guards sphere of extraterritorial operations, and the latter likely does not want to share the prestige and financial benefits with a rival institution. While army presence in Syria was symbolic, the IRGC and its non-Iranian Shiite militias engage in heavy combat.

Apropos engagement in combat, the Revolutionary Guards leadership insists its forces are present in Syria in an “advisory” capacity. However, the IRGC fatalities taken into consideration, along with video footage of IRGC forces engaging in combat as early as 2013, the Guard’s leadership must have a very broad definition of the role of military advisers, which allows them to engage in a wide range of military activities in Syria. The fact that the IRGC engaged in ground operations early in the Syrian conflict reflects how committed the IRGC was to the Syrian regime, and how unlikely they are to back down from supporting it.

Persian language open source materials provide good information about what Iran calls its “martyrs” in Syria. However, the branch affiliation of less than half of the IRGC’s fatalities in Syria is known.

Figure 1: Total Iranian nationals killed in combat in Syria from January 19, 2012 – March 30, 2017 by branch

Only 36 members of the IRGC’s extraterritorial operations Quds Force (IRGC QF) were identified among combat fatalities, but due to the secretive nature of the Quds Force, there is every reason to believe the QF servicemen are statistically overrepresented among the 284 IRGC combat fatalities whose exact branch could not be determined.

More surprising is identification of 122 Revolutionary Guards combat fatalities who served in the IRGC Ground Forces. IRGC Ground Forces are trained for the dual purposes of resisting a land invasion and suppressing domestic unrest—like the post electoral anti-regime rallies in 2009—in their native provinces, making them unsuitable for anti-insurgency warfare. The structure of the IRGC Ground Forces dates back to the revolution of 1979 and emergence of the Guards from revolutionary chaos. As institutions of the Shah’s regime collapsed, IRGC cells emerged in each province to fill the power vacuum. Until today, the structure of the IRGC Ground Forces follows the administrative divisions of Iran: there are 32 IRGC provincial units corresponding to one for each province and two for Tehran. The units, which are composed of the natives of the province in which the IRGC Ground Force members serve, were renamed and restructured in 2007 as part of the IRGC leadership’s Mosaic Doctrine, aiming at securing Iran against “decapitation” attempts by the United States.

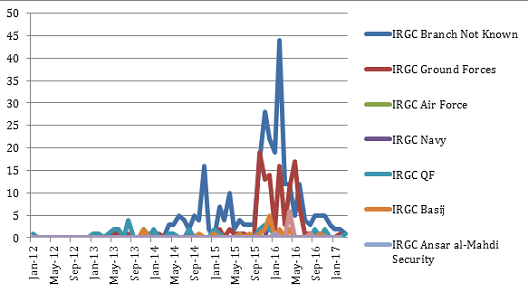

As reflected in Figure 2, IRGC Ground Forces suffered heavy losses from October 2015 onwards. This likely reflects the deployment of the Ground Forces as the nature of the war in Syria changed. The data reflects an increase in deaths from late 2014 until mid-2015, when Syrian rebels advanced against the Syrian regime, inflicting heavy losses, and the regime relied more heavily on its allies and paramilitary groups to keep it afloat. Post October 2015 there is a spike in the deaths of all IRGC forces, but particularly the Ground Forces. This may reflect large scale Ground Forces deployment in Syria in the wake of even heavier Quds Force losses in the war. Moreover, September 30, 2015 was the start of the Russian intervention, and the IRGC likely ramped up their forces to take advantage of, if not in coordination with, Russia’s presence.

Figure 2: Iranian nationals killed in combat in Syria from January 19, 2012 – March 30, 2017 by branch and month.

Increased deployment of IRGC Ground Forces in Syria rapidly changed the nature of the IRGC from a political army countering internal threats to the regime in Tehran to an expeditionary force capable of power projection faraway from Iran’s borders. This transformation is bound to impact security dynamics in the Middle East and Central Asia for two reasons:

The generation of mid-level field commanders, during the Iran/Iraq war from 1980-1988, rose to prominence within the ranks of the IRGC and in politics along with the growing economy after the war ended. The generation of IRGC officers now spending their formative years in Syria will dominate the military, political, and economic leadership of the Islamic Republic in the coming years. With the IRGC’s Syria doctrine a blueprint for winning future conflicts, that generation is not likely to show greater moderation when it comes to expeditionary warfare. If anything, the lesson from Syria is that scorched-earth tactics are the only way to ensure victory.

Just as importantly, the IRGC Quds Force, previously a small part of the Revolutionary Guards between 2,000 and 5,000, is likely to become more dominant. The Quds Force is the IRGC’s special forces and focuses on extraterritorial operations. As a ground invasion feels less likely to Iran, the best way to secure its regional interests is through these expeditionary campaigns and change the entire IRGC to act as one expeditionary force.

While the increased structural agility and battle-hardened forces give Iran the ability to intervene more easily in future regional conflicts, the war’s outcome may increase Iran’s willingness to be involved in other conflicts. Syria is a testing ground, and from the IRGC’s perspective, a successful campaign.

Ali Alfoneh is a Nonresident Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council.

Image: Photo: Members of Iran's Revolutionary Guards hold pictures of their Brigadier General Hossein Hamedani during his funeral in Tehran, Iran in this October 11, 2015 file photo. REUTERS/Raheb Homavandi/TIMA/Files