Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi recently announced his new war against corruption. In using the term “war,” he intended to convey the difficulty of implementing a productive policy to fight corruption. Abadi hopes to build on his successes in the war against the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and the crisis with Kurdistan by turning his attention to a popular and persistent demand: fighting corruption. International financial institutions and nonprofit organizations—including the World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF)- identify rampant corruption as a main impediment to development in Iraq, and Transparency International consistently rank Iraq among the most corrupt countries.

Notably, Iraqis hold different expectations on how the “war against corruption” should unfold and diverse views on remedies offered by international organizations. However, the common popular understanding of an anti-corruption campaign includes jailing complicit senior officials and minimizing growing income inequality. For this to happen and be credible, there has to be a serious effort to reform the justice system, itself suffering from corruption and politicization. But this would be a long process and require careful management of popular expectations, which could also mean decoupling anti-corruption campaigns from electoral calculations that some think to be the drivers behind Abadi’s escalating rhetoric against corruption. So far, the Prime Minister succeeded in avoiding populist actions that are legally dubious just to meet the legitimate public demands to combat the rampant corruption. However, during the last week, various lists of senior politicians to be targeted for their corruption spread in the social media, both raising popular expectations and confusing observers as how would this new “war” be conducted.

A main challenge here is to produce a vision that reconciles anti-corruption measures with more long term requirements for economic reformation, which sometimes include executing less popular measures. For example, while international organizations agree on the urgent need to fight corruption, they also insist on other types of reformation that Iraq’s political class would likely view as too burdensome. The World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF), for example, demand public sector reform, which could include salary reductions and a decrease in the government workforce. Clearly, employment in public institutions has long been used by political parties as a patronage tool to increase their influence. Thus, some proposed reforms in this sector face unequivocal opposition by public servants and most parliamentarians think that such reductions would harm them politically.

Abadi repeatedly denied reports of public sector salary reductions (as in his November 29th press conference), understanding that a battle with Iraq’s immense, but mostly dysfunctional bureaucratic machine, would damage both him and his party. Instead, he opted for more control over public sector appointments and long-term policies that would stimulate the private sector and ostensibly create employment opportunities. Not everybody is happy with those measures. For Iraq’s youth, hundreds of thousands of whom graduate every year from universities and institutions geared toward training public servants, a shrinking public sector implies imminent unemployment, especially in light of a private sector that has fallen behind and would need time to rebuild capacity, consumer confidence, and foreign investment. As with many welfare-based Arab countries, public service remains an attractive option, given the minimal effort involved, job security, and pension it offers.

In fact, many Iraqis demand ta’yeen (appointment in the public sector), taking to the streets to make their opinion known. For example, a group of part-time teachers in Iraq’s southern city of Basra demonstrated last September to pressure to accept them as permanent staff and earn the same salaries and benefits given to full-time teachers. One female teacher angrily complained to a local radio station of their unfair treatment and threatened continued protests if the government did not meet their demands for a more secure future. Just days earlier, university professors in Baghdad also protested a salary plan that would have reduced their earnings. In the same week, reporting from Mosul (which was recently liberated from ISIS), Niqash said that many local state employees were complaining that the government has not paid their salaries despite promises to do so. The report describes a gloomy picture where economic hardship and high unemployment are mixed with precarious security situation and rivalries between militias.

Rather than reducing state operational expenditures, the government sought to reduce the budget deficit—a situation exacerbated by the decline of oil prices and increased military expenses. Following advice from the World Bank and IMF, it took steps to increase government revenue by restructuring the tax system and raising prices for some services. A recent plan to privatize bill collection for electricity has triggered a wave of protests in southern Iraq, with many people arguing that it benefits investors at the expense of consumers. Government officials and economists have countered, claiming that the plan will not only keep electricity expenses the same but also improve service and revenue collection, but many are still doubtful.

Iraq will have a tough time balancing reforms demanded by international organizations, and reforms imagined by ordinary Iraqis—even more so in an electoral season when opponents will readily politicize economic measures and populist discourse escalates. Abadi might have touched the right nerve by emphasizing the danger of corruption and cultivating the image of corruption fighter. It is unclear, however, whether his main motive is to gain more popular support before the election or follow a well-crafted plan of economic reform. The former might lead him to lean towards a populist form of anti-corruption, which could mean clashing with influential political groups and power centers in the country. The latter will require carefully managing public expectations and avoiding attempts to politicize the reform agenda.

Harith Hasan is is a senior non-resident fellow with the Rafik Hariri Center. Follow him on Twitter @harith_hasan.

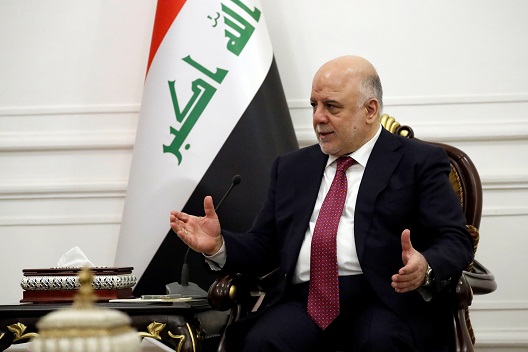

Image: Iraq's Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi speaks with U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson (not pictured) in Baghdad, Iraq October 23, 2017. REUTERS/Alex Brandon/Pool