The debate about the role of Islam in new constitutions in Libya, Tunisia, and Egypt has begun with the formulation of the role of Islamic sharia in lawmaking: should Islamic sharia be the source, the principal source, or a source among sources of legislation? Ennahdha, the Islamic ruling party in Tunisia, eschewed the question by not referencing Islamic sharia at all in the draft constitution. The failed Egyptian constitution of 2012 established Islamic sharia as the principal source of legislation and created a role for the clerics of al-Azhar to consult ex ante in lawmaking. Neither borrowed the formulation of the Iraqi constitution, which bans laws that “contradict the established provisions of Islam,” or Pakistan, where an Islamic court adjudicates questions of Islamic law with the same authority as the Supreme Court.

The debate about the role of Islam in new constitutions in Libya, Tunisia, and Egypt has begun with the formulation of the role of Islamic sharia in lawmaking: should Islamic sharia be the source, the principal source, or a source among sources of legislation? Ennahdha, the Islamic ruling party in Tunisia, eschewed the question by not referencing Islamic sharia at all in the draft constitution. The failed Egyptian constitution of 2012 established Islamic sharia as the principal source of legislation and created a role for the clerics of al-Azhar to consult ex ante in lawmaking. Neither borrowed the formulation of the Iraqi constitution, which bans laws that “contradict the established provisions of Islam,” or Pakistan, where an Islamic court adjudicates questions of Islamic law with the same authority as the Supreme Court.

These textual and institutional arrangements will play an important role in the upcoming constitutional debate in Libya. In the next few months, Libyans will elect sixty members to a constituent assembly that, according to the interim constitutional declaration, will have four months to submit a draft constitution to public referendum. Libyans from across the political spectrum think that questions of Islam and Islamic law are important for the constituent assembly to consider. Not only that, but according to a nationally representative survey conducted by the University of Benghazi, 40 percent of Libyans prefer that Islamic sharia be the only source of legislation.

But taken alone, the vague formulations of “a source” or “the source” of legislation give little guidance to lawmakers or courts in implementing a new constitutional order. For one thing, a common critique is that Islamic law is a sprawling construct with infinite interpretations, at the first level divided into various schools. Even this critique, however, misses an opportunity to expand the debate over constitution making in the Middle East: how can the conception of Islamic law be broadened to describe other features of democratic constitutional design relevant to Libya?

One approach is to look for precedents in the history of Islamic law for what we now call international standards. For example, Islamic legal scholar and human-rights activist Chibli Mallat links the Quranic clause on religious freedom—la ikrah fil-din, or “no compulsion in religion”—to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

Furthermore, in Fall and Rise of the Islamic State, Noah Feldman argues that the balance of power, executive constraint, and the rule of law were fundamental aspects of Islamic governance in the Ottoman period—challenging the Western historical record that paints the Middle East as a perpetual haven of executive strongmen. Indeed, Ottoman legal scholars—the ‘ulama’—had an essential role in interpreting Islamic law to constrain and in some cases reverse decisions by the sultan. The development and interpretation of law was strictly bounded as an interaction between the sultan as the executive, God through religious law, and jurists and scholars as interpreters of the law.

A conference in June, hosted by Democracy Reporting International and the Libyan Center for Strategic & Future Studies, explored deep questions of Islamic constitutionalism in four panels drawing on leading experts from around the world. The strategy was to explore concepts of democracy through an Islamic lens. The four panels covered themes of human rights, women’s rights, judicial systems, and the balance of power. The conference report, including papers on these themes written by experts prior to the conference, is available online. Policymakers, future members of the constituent assembly, and democracy advocates should take the findings of the conference seriously as a way of building on Islamic law to develop democratic institutions in Libya’s transitional period.

Duncan Pickard is a nonresident fellow at the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East. The opinions expressed here are his own.

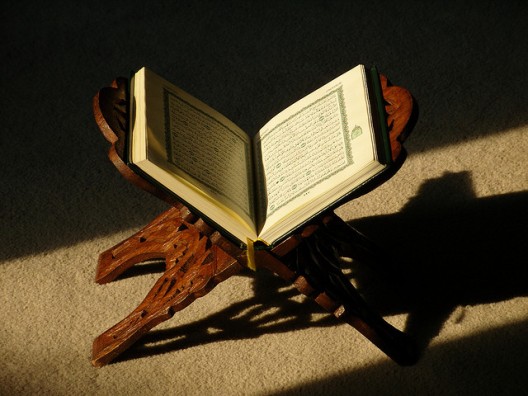

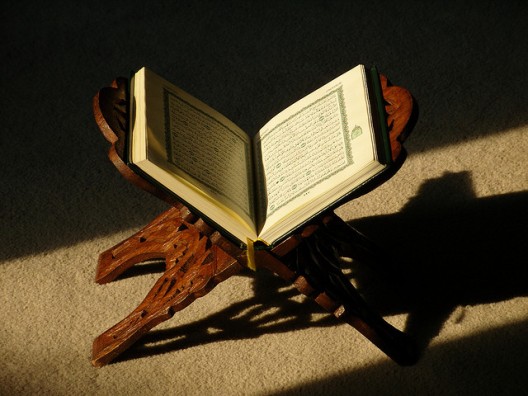

Image: The Holy Quran (Photo: Flickr/Zaid al Balushi/CC license)