Observers have described Jordan as an oasis of calmness and stability in the stormy uprisings of the Arab world during 2011; but regular weekly demonstrations across the country suggest it is not the stable sanctuary that King Abdullah hoped it to be.

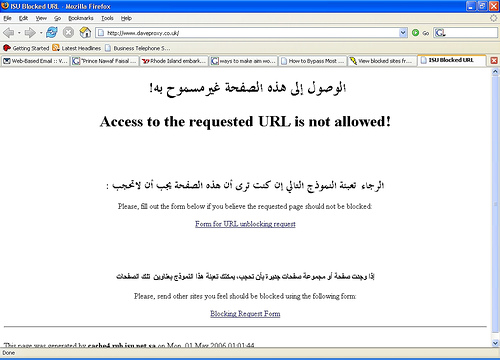

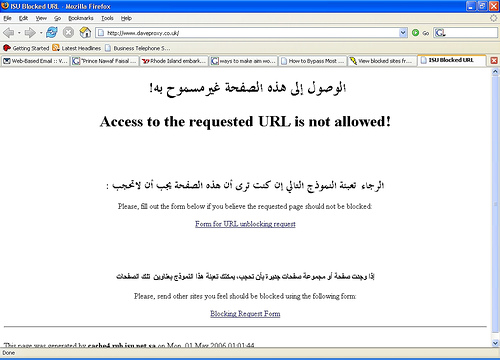

Activists were shocked when the government blocked more than 300 websites over speculation that the lower house of parliament planned to amend the press and publications law. Prime Minister Abdullah Nsour tried to justify the blackout by claiming that the managers for those websites were unregistered, but such claims are disingenuous at best. Commentators in the Jordanian blogosphere and independent media consist overwhelmingly of ordinary citizens—not journalists—and would require membership in the Jordanian Journalists Association as an editor-in-chief and a hefty registration fee of 1000 JD (1,400 USD) to even begin the registration process.

The anticipatory measure taken by the cabinet indicates a desire to minimize public debate and control the anger and frustration that would no doubt result from blocking websites critical of government policy. Alaa al-Fazzaa, director of one of the blocked websites (khabarjo.net), wondered: “Why would Nsour and his cabinet need to censor media?” Al-Fazzaa remains convinced that the enforcement of the controversial press and publications law at this time suggests an effort to mitigate resistance to imminent unpopular policies to be put forth by the Jordanian government.

It appears that Nsour is using this controversy as a diversionary tactic. Not only would the online media blackout naturally limit the exposure of opposition activities, protests, and other forms of free expression, the measure would also preoccupy activists with the press and publications law—diverting attention away from the expected rise in electricity and bread prices. As point of interest, numerous websites have escaped the government-imposed clampdown (such as international websites that remain unregistered in Jordan), but such sites significantly lower the bar in their level of criticism.

One senior government official said that it is considering new methods to block social media websites—the next innovative step in Jordan’s race to become the most autocratic country in the Middle East with regard to free expression. The press and publications law would thereby take on an even more expansive interpretation. Before taking sure measures, however, Nsour should ask himself: What is the cost of pushing Jordanian youth, particularly those who are politically active, to go to the street?

Representatives of the blocked websites have refused to remain complacent, strenuously arguing the unconstitutionality of the press and publications law. These representatives have already devised plans to confront the government, including coordination with international organizations to pressure decision makers in the kingdom. Alaa al-Fazzaa, among other employees of the blocked sites, met with Reporters Without Borders, the Committee to Protect Journalists, Human Rights Watch, and the International Publishers Association on June 20 to discuss the international law surrounding the issue and explore strategies aimed at repealing the legislation. These international organizations have also sent a direct request to King Abdullah, leveraging his public guarantees for freedom of expression, to stop the censorship. Website representatives also met with parliamentarians, members of the upper house, the cabinet, and local civil society organizations to exert additional pressure on the government, al-Fazzaa said.

Website employees also took technical steps to circumvent government censorship, such as opening their websites to use via proxy servers, replacing commercial URLs with private network addresses, or using individual Facebook to promote their work.

Government resistance to changing its stance emerged quickly. When website employees met with the National Education Committee in the lower house—the authors of the controversial legislation—to push the parliamentarians to amend or repeal the law, they were met with evasive, dismissive, or defensive responses from MPs. Many speculate that they received direct instructions from the government to forget drop the issue, further highlighting the lack of independence in the parliament.

Jordan would never make a move limiting free expression to this extent without at least implicit approval from its traditional Gulf allies. This recent clampdown suggests that Nsour got the green light from Jordan’s royal neighbors, sensing that such censorship would not threaten regional stability. His stance is bolstered by similar regional policies, such as Saudi Arabia’s tight control over social media space.

Given the dramatic changes of the Arab Spring witnessed over the past two years, King Abdullah would be wise to expand the political space, not restrict it. The criticisms of international organizations on Jordan’s tightening of free expression would certainly create a thorn in the side of the government in terms of international diplomacy, particularly with strong allies such as the United States. Embarrassment in the global press may seem inconsequential, but the exposure of such indiscretions on the part of other Arab autocrats contributed to the Arab uprisings and the continuing social transitions.

Clearly, tech-savvy youth have demonstrated their ability to compete with government restrictions on their activity, relegating policies such as the press and publications law to nothing more than an insult. If the Jordanian government means to celebrate another round of so-called free-and-fair parliamentary elections as it did in 2011—despite the unrest gripping the region—it would be wise to allow its MPs to actually represent its people, lest it suffer the same fate as other fallen autocrats.

Wael Al-Khatib is an Amman-based sociocultural anthropologist studying political development in Jordan.

Photo: Curtis Palmer

Image: Blocked%20web%20in%20SA.jpg