Netanyahu and MBS are not done with Trump just yet

Reports of an undisclosed rendezvous on November 22 between Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Mohammed bin Salman (MBS), the presumptive heir to the Saudi throne, raised eyebrows for its curious timing. One might have expected that, with Donald Trump already in the twilight of his presidency, Netanyahu and MBS would have deferred their tryst until the end of January and bestowed this welcome upgrade in Israeli-Arab relations as a housewarming gift to the incoming Joe Biden administration. Mitigating circumstances—chiefly, their shared anxieties over Iranian aggression—dictated precisely the opposite.

The meeting in Neom, the Red Sea venue showcasing Saudi Arabia’s vision of a “new future,” was another milestone in the creeping rapprochement between Riyadh and Jerusalem. Official Saudi denials of Netanyahu’s appointment with the crown prince were to be anticipated—the kingdom has signaled repeatedly that it is yet unprepared for full normalization with Israel—but are less than credible; the detection of the prime minister’s poorly camouflaged flight path to Neom and a chorus of sourced leaks have served to confirm that the summit, facilitated by US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, did indeed transpire. Smokescreens notwithstanding, the principals got what they wanted.

Netanyahu and MBS are circling their wagons. Like other Trump fans, whose team has started packing its bags in Washington, they are hunkering down now to meet the challenges of the impending post-Trump era.

With Israel on the verge of its fourth election in less than two years, the prime minister is fighting for both his political career and his personal freedom. A majority of Israel’s right-wing constituency, which holds Netanyahu directly responsible for the crisis of public confidence in national institutions, is actively engaged in a debate over who should replace him. Already facing three outstanding indictments, he confronts the possibility of a new commission that would investigate his role in a much-maligned bargain to purchase multiple submarines from Germany.

The prospects of the Saudi prince, as sovereign-in-waiting, are likewise clouded by his deep involvement in escapades gone bad—most prominently the intractable civil war in Yemen and the brutal killing of Saudi dissident and Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi—which have caused him to be vilified on the world stage. Like Israel’s premier, MBS is in desperate need of some positive news that might both deflect attention from his toxic shortcomings and rehabilitate his image and leadership.

These specific objectives would have been equally well-promoted if Netanyahu and MBS had reserved the prize of their extraordinary huddle for Biden’s watch. The masters of both Israel and Saudi Arabia, after all, will have significant work to do if they hope to gain the confidence of their many Democratic critics. What tipped the scale in favor of handing this win to Trump—the supposed “lame duck” incumbent—was the potential for quid pro quos that could soon be out of reach. The November 27 assassination of Iranian nuclear physicist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh is a case in point.

US President-elect Biden has telegraphed that he plans to “elevate diplomacy as the premier tool of our global engagement,” clarifying in September that he is “ready to walk the path of diplomacy if Iran takes steps to show it is ready too.” His nomination of a cohort of seasoned establishment professionals to fill senior national security positions underscores this return to traditional foreign policy after the unconventionality of the Trump years.

The Fakhrizadeh killing, which will likely complicate any effort to resume negotiations with Iran, would not have been an action that President-elect Biden would have been inclined to sanction.

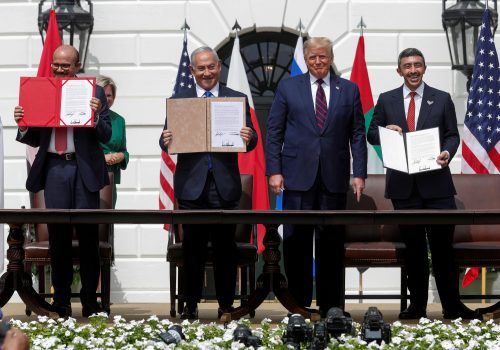

No single encounter between the Israeli prime minister and the Saudi crown prince could alter this calculus: Biden offered high praise for the Trump-chaperoned Abraham Accords between Israel, the United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain—an agreement that he will desire almost certainly to build upon—but his administration will manage America’s affairs methodically and circumspectly, not subscribing compulsively to Israeli or Saudi wishes, as Trump often did. Netanyahu’s warnings to Biden against reverting to the Iran nuclear deal are further evidence that the prime minister understands this predicament and is now adjusting to a new reality.

That’s why staying in the best graces of the departing president is a logical, short-term hedge for the likes of Netanyahu and MBS, who fear an imminent devaluation of their US currency. Trump, who has made no secret of his favoritism for those whom he considers to be “a good friend of mine,” is perfectly primed to respond effusively to overtures that cast his tenure in a glowing light. The groundbreaking dialogue in Neom fit this bill exactly (at any rate, the actual trophy of a formal treaty between the Jewish state and the Sunni kingdom remains on the shelf to be bequeathed to Biden at a later date).

With aspirations of mounting a campaign to recapture the White House in 2024, Trump is predisposed to display exceptional gratitude toward those who might allow him to continue looking successful and presidential right up until Biden’s inauguration. The Saudi-Israeli consultation provided the added bonus of invigorating the Abraham Accords, which have been popular among Trump’s Evangelical Christian base. A last-ditch attempt to end the ongoing feud between Saudi Arabia and Qatar—Trump’s senior advisor Jared Kushner made an eleventh-hour sortie to see the Saudi crown prince on December 1—can be decrypted this way as well. Netanyahu and MBS can hope for any number of rewards for their cooperation.

Recent actions by Secretary Pompeo lend credence to this theory of Trumpian Hail Mary passes. On November 19, Pompeo—who has his own apparent designs on the presidency—paid unprecedented back-to-back visits to a Israeli community in the West Bank and to the Golan Heights, giving tangible expression to Trump’s recognition of Israel’s presence in both places. Israeli defense officials suspect that the outgoing administration could also authorize the delivery of top-notch, sophisticated weapons to Saudi Arabia. Following President Barack Obama’s example of abstaining on UN Security Council Resolution 2334—which censured Israel’s settlement enterprise—during the waning days of his term, Trump would have no compunction about enacting his agenda without any particular regard for the views of his successor.

The biggest ticket is Iran, by far the foremost concern of both Israel and Saudi Arabia; both worry that a conciliatory approach could put their countries (and others) at grave risk. The elimination of Fakhrizadeh, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps brigadier-general considered by US and Israeli intelligence to be the “driving force behind Iran’s nuclear weapons program for two decades”—which ended in 2003—stands now to ignite a cycle of vengeance that decimates any chance of compromise. Trump’s trademark seems to be all over the operation.

Taking a brief intermission from his steady torrent of accusations that the 2020 US elections were rife with fraud, President Trump took conspicuous note on Twitter of Fakhrizadeh’s death, even taking the unusual step of retweeting a Hebrew-language burst that reported on Iran’s confirmation of the scientist’s demise. Whether agents of the US and/or Israel carried it out—Netanyahu warned an audience pointedly in 2018 to “remember [Fakhrizadeh’s] name”—or some other party, the mission appears to have won Trump’s blessing and would have doubtfully occurred otherwise. While true that such a precision strike would have required extensive research and preparation, it is also true that those determined to thwart Iran’s nuclear ambitions would have a variety of rainy-day contingencies available, and that these schemes would best be executed while the current US president is still cleaning off his desk.

Momentum is now with the advocates of a tough posture on Iran. Already on the brink of a potential escalation, the Persian Gulf is poised to turn more crowded and tense with the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz and an accompanying cohort of other US warships back in the theater. Although the naval vessels are being dispatched ostensibly to “provide combat support and air cover as US troops withdraw from Iraq and Afghanistan by January 15,” their presence enables the exiting commander-in-chief—who has previously pursued options for a military strike against Iran’s nuclear infrastructure—to order some parting shot across Iran’s bow if the spirit moves him.

Netanyahu and MBS may wind up getting the showdown they crave with Iran, but a powder keg is a dangerous thing to place in the hands of Trump, whose strategy—as one of his blunt aides told CNN—is “to set so many fires that it will be hard for the Biden administration to put them all out.” The coming weeks will tell whether a Trump decision to leave office in a blaze of glory will engulf the Middle East in flames.

Shalom Lipner is a nonresident senior fellow for Middle East Programs at the Atlantic Council. From 1990 to 2016, he served seven consecutive premiers at the Prime Minister’s Office in Jerusalem. Follow him on Twitter @ShalomLipner.

Image: Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu during a press conference on the flight from Israel to Abu Dhabi via Saudi Arabia in Jerusalem, Israel on August 31, 2020. Israel and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) gave this Monday ( 31) a symbolic step forward in the process of normalization of relations with the first flight between the two countries where Netanyahu encouraged the United Arab Emirates to return the visit.