The reciprocal criticisms between the Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and his Shia rival, Moqtada al-Sadr, reflect the changing dynamics of Shia politics in Iraq. On several occasions, Sadr, the leader of the Iraqi Islamist Sadrist Movement, warned of a possible “return to dictatorship” in Iraq while denouncing the government’s “exclusionary” policies. Critical of Maliki’s recent visit to Washington DC in October, he condemned it as an attempt by the prime minister to seek US support for a third term in office. Maliki’s office replied with an unusually defiant statement, reminding Sadr that his militias were largely involved in the sectarian violence during the civil war and accusing him of participating in efforts sponsored by hostile regional powers to unseat Maliki. The statement threatened a harsh reprisal in the future should Sadr not change his behaviour.

The reciprocal criticisms between the Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and his Shia rival, Moqtada al-Sadr, reflect the changing dynamics of Shia politics in Iraq. On several occasions, Sadr, the leader of the Iraqi Islamist Sadrist Movement, warned of a possible “return to dictatorship” in Iraq while denouncing the government’s “exclusionary” policies. Critical of Maliki’s recent visit to Washington DC in October, he condemned it as an attempt by the prime minister to seek US support for a third term in office. Maliki’s office replied with an unusually defiant statement, reminding Sadr that his militias were largely involved in the sectarian violence during the civil war and accusing him of participating in efforts sponsored by hostile regional powers to unseat Maliki. The statement threatened a harsh reprisal in the future should Sadr not change his behaviour.

Iraqi commentators saw in those public attacks an early initiation of the electoral campaign for the general election due to take place in April 2014. Internal competition over the position of prime minister among the three major Shia forces—the Maliki-led State of Law coalition, the Sadrist Movement, and the Supreme Islamic Council led by Ammar al-Hakim—will exert unprecedented influence over the course of the elections. Although Sunni-Shia and Arab-Kurdish divides will keep playing important roles in shaping political alliances, the growing polarization resulting from Maliki’s legacy will likely dominate the electoral discourse and post-election trends.

Maliki consolidated his power by controlling or coopting public institutions—including the military and security services. For Sadr and other key politicians, Maliki’s power grab threatened the political space in which they operate, sparking the fear that his hold on these institutions might crystallize if it remained unchallenged. This opinion was shared by Kurdish leader Massoud Barzani, Sunni leader Osama al-Nujeifi, and Shia liberal Ayad Alawi, Maliki’s main rival during the general election in 2010. Sadr, unlike his fellow Kurdish and Sunni leaders however, felt increasingly pressed to engage more heavily in this confrontation given his direct competition with Maliki for the same constituency. Despite the solid support base in the poor and crowded neighborhoods of Shia cities, Sadr felt compelled to present himself as a leading force for Iraqi Shias to counter Maliki’s potential to seize the Shia vote.

By publicly calling Maliki out, Sadr sought to benefit from the increasing public dissatisfaction with Maliki in order to broaden his constituency and Maliki’s critics welcomed Sadr’s new aggressive stance. Some commentators suggested a genuine transformation in his character—rather than a politically pragmatic shift to the center—from a focus on previously closed and factional interests into openness and effective interaction with different groups and ideas. Many reference how the Sadrist Movement has refrained from an explicitly sectarian discourse (despite the participation of its militias in sectarian violence that pervaded Baghdad and other mixed cities in 2006 and 2007). But both Sadrists and Iraqi Sunnis distrust most opposition groups (Maliki, in particular) that returned to the country from exile after 2003. Capitalizing on this sentiment, the Movement has deftly used the Sadr family legacy, based on a nationalist ideology with Islamic traits, to reposition itself at the center of political spectrum in recent months.

The Sadrists demonstrated this new approach in parliament when they allied with non-Shia forces, whether to push legislation aimed at reducing the federal government’s powers or to reject proposals by Maliki (such as the infrastructure law). Sadr participated in meetings that took place in Erbil (in May 2012) with Kurdish, Sunni, and liberal parties and even backed a motion to vote Maliki out of office. Although Iranian pressure on Sadr and President Jalal Talabani prevented Maliki’s opposition from success, these meetings illustrate the extent to which Sadr can push his own policy agenda.

In the context of sectarian polarization, reinforced by a system based on ethno-sectarian apportionment of power, Shia, Sunni, and Kurdish parties share the tendency to radicalize their discourse and move further to the right in defending their respective communal interests. However, some of Sadr’s Shia rivals currently lack the confidence in his commitment to the communal interest. Despite being a part of Shia politics, the Sadrist Movement has the social and cultural particularity and a distinct collective solidarity that characterize an autonomous, self-contained group. Sadrists feel that their antagonism towards Sunnis falls secondary to the conflict with Maliki, who seeks to weaken and isolate both forces. They also see Sunni and Kurdish parties as potential allies in any future attempt to replace him. Thus, Sadrists try to balance their need to appeal to these parties and their loyalty to the communal interest. They fully realize that the failure to strike such a balance between communal and national priorities can cause great political damage—as in the case of Ayad Alawi whose previous appeal to the Sunni vote was not balanced by equally serious efforts to win over the Shia constituency.

One must also acknowledge the personal nature of this rivalry between Sadr and Maliki. Sadr considers himself part of the leadership legacy that his family represented in Iraq. In his statements, he refers to his father as a religious and ethical authority that must be followed and obeyed. Maliki does not possess such a legacy and is seen by Sadr as lacking the sufficient legitimacy to lead the country. While Sadr derives his power from the charismatic character of his family, Maliki built most of his influence through the more shifting politics of patronage. Their political duel reflects two different concepts of leadership and political activism.

Maliki realizes that his diminished capacity to secure the support of his Shia rivals means that he should embrace a reconciliatory approach towards Kurdish and Sunni parties. In trying to overcome past disagreements over oil deals with international companies in disputed areas, he recently adopted a more flexible attitude in his government’s relations with Kurdistan Region . However, even if Massoud Barzani, the President of Iraqi Kurdistan, is less interested today in seeing Maliki unseated, his partnership with the latter cannot be guaranteed in the short-run. If the Kurds feel that they can secure similar or more generous concessions from Maliki’s rivals, they will likely support them in any negotiation to form a new government.

Maliki might seek to bridge the widened gap with the Sunnis by rebuilding the broken ties with the Awakening Groups (AGs) that fought against al-Qaeda together with the US Army in Anbar and other Sunni provinces. Many observers view the government’s failure to maintain workable relations with AGs as a significant factor in the recent deterioration of the security situation. Maliki could again face the same polarization dilemma that he could not resolve in his past seven years in office. On the one hand, he needs to make inroads to Sunni forces while, on the other, avoid making concessions that enrage Shia hardliners allied with him. Considering that the pre-election climate inhibits the chances for strategic compromise, it seems unlikely that Maliki would gain tangible support from major Sunni forces in the foreseeable future.

This dynamic might help explain Maliki’s impatience with Sadr. As rivals, they must contend not only for the Shia constituency and the backing of the Supreme Islamic Council, but also for Kurdish and Sunni cooperation after the election. The Maliki-Sadr conflict will play a crucial role in determining the future path of Iraqi politics and deciding who will be the next prime minister.

Harith Hasan is an independent Iraqi academic and political analyst of Iraq and Middle East affairs.

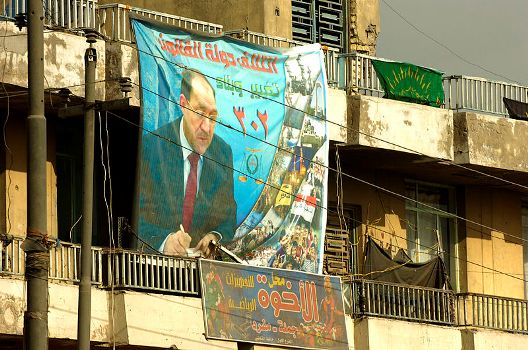

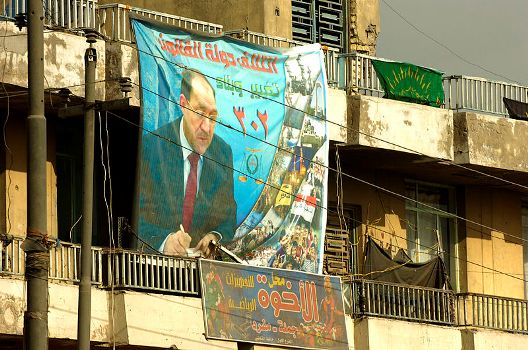

Image: A campaign poster for Iraqi Prime Minister Al-Maliki hangs from a building in Baghdad’s Sadr City district, Iraq, January 2009. (Photo: Wikimedia)