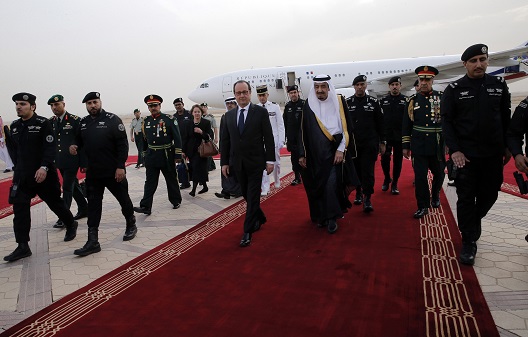

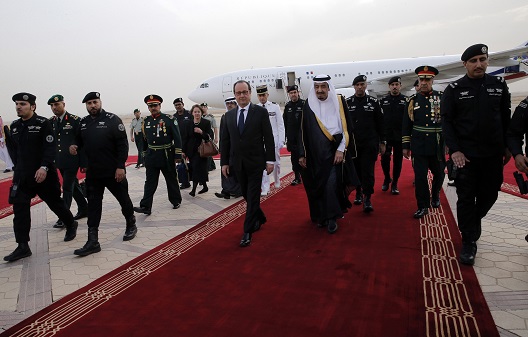

President Barack Obama will host the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) leaders next week at the White House and Camp David to discuss security issues in the Middle East. As preparations for the visit are underway, Saudi Arabia invited French President Francois Hollande as a “guest of honor” to Riyadh to discuss regional issues with Gulf Arab leaders. Hollande is known to have the toughest stance against Iran’s hegemony in the region, mainly in Syria, and his presence was significant.

President Barack Obama will host the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) leaders next week at the White House and Camp David to discuss security issues in the Middle East. As preparations for the visit are underway, Saudi Arabia invited French President Francois Hollande as a “guest of honor” to Riyadh to discuss regional issues with Gulf Arab leaders. Hollande is known to have the toughest stance against Iran’s hegemony in the region, mainly in Syria, and his presence was significant.

During the preparatory meeting on May 5, Saudi King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud and Hollande agreed on two points—both of which shed a light on what GCC leaders expect from the meeting with Obama next week: First, they confirmed the need to reach a robust, lasting, verifiable, undisputed, and binding deal with Iran, which must not destabilize the security and stability of the region, nor threaten the security and stability of Iran’s neighbors.” Second, they reiterated that there would be no future for President Bashar al-Assad of Syria after four years of civil war. Although Obama does not differ on these two points, the problem lies in how his administration perceives regional threats and prioritizes efforts to mitigate them.

Obama views the nuclear deal with Iran as mutually beneficial; it would stabilize the region by stripping Iran of its capacity to weaponized nuclear power. He also does not see Assad as a viable leader of Syria. But Obama does not yet appreciate the extent to which Iran will feel empowered to finance its proxies across the region once sanctions are lifted. Increased trade and international acceptance would increase Iran’s influence over Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen, further destabilizing the region with sectarian tension as it pursues its hegemonic ambitions.

For Syria, continued US indecision on how to remove Assad and the snail’s pace approach on training and equipping Syrian rebels have frustrated Arab leaders who had hoped for more robust US leadership. As events in Syria demonstrates, these leaders have started taking matters into their own hands. The Nusra Front and Ahrar al-Sham have consolidated their leadership under the Army of Conquest coalition and now fight together. This coalition came about through increased cooperation between Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Turkey, a new alliance with the will and means to change the facts on the ground in Syria, much faster than the rebel training by the United States.

Containing Iranian hegemony in the region through Assad’s removal should be the main points on the table for the meeting between Obama and the GCC leaders next week to be effective—which should place Syria at the top of the agenda.

The meeting comes at a time when Iran is losing ground in Syria. As the June 30 deadline to reach a nuclear deal approaches, Iran will try to maintain its gains. After four years of a multi-billion dollar investment in military operations, propping up the economy, and providing services, Iran will not accept defeat nor will it leave Syria if or when Assad falls. Iran will demand that the United States guarantee its control over strategic routes in Syria: the coastline to Homs and Damascus and Qalamoun along the Lebanese border to guarantee Hezbollah’s protection. If granted, Iran will likely withdraw, even if it means ceding control to radical Islamists in Syria’s north.

But without the GCC’s approval and coordination with factions on the ground, the United States cannot guarantee Iran anything and, given their own geopolitical concerns, Gulf leaders will not likely approve of any Iranian control in Syria—even without Assad. Iranian power projection inside Syria would only prolong the war and delay any peaceful solution or prospects for stability. Iran would use Shia and Alawites in Syria to boost its expansion agenda, which in turn would support its influence over Lebanon and Iraq and pose a continuous threat on the doorstep of Gulf countries.

Yet Obama’s priority remains his nuclear deal with Iran, for which he needs GCC support. He will likely try to ease Gulf security concerns by offering stronger security cooperation with the Gulf States and, according to recent statements by White House officials, promise to defend the GCC states against any threats from Iran. However, the real Iranian threat for the GCC and others in the Middle East is not Iran militarily attacking or invading them; it is Iran’s explicit goal of exporting the Islamic Revolution and exerting subtle control over the region.

The United States can only calm the Gulf leaders’ concerns by guaranteeing that Iran will not receive US approval to boost its hegemony in the region. In this context, Assad’s removal is vital. Without Assad, Hezbollah will be cut-off and Iran will have to retreat. Without the Western support and with Arab countries aligned against it, Iran cannot hope to sustain its control. With the right security assurances, the GCC could support the nuclear deal. Ultimately, the United States would satisfy its interests in limiting Iranian nuclear capacity, Iran’s interests in lifting sanctions and reengaging on the international stage, the Gulf’s interests in limiting Iran’s regional influence, and Syrian interests by removing Assad and restoring hopes for a stable future.

The meeting next week will determine the GCC’s next steps in Syria. Gulf support for unified operations against Assad and Shia militias in Syria will likely continue, with or without US support. It will not be enough to reiterate the US position on Assad’s illegitimacy and the need to remove him from power. Neither will it suffice to show off US training for the small number of vetted Syrian opposition fighters. A slow approach towards the Syrian crisis will only show the GCC leaders that the United States remains uncommitted to their regional security interests. If Obama decides, however, to offer a no-fly zone and a train and equip program “on steroids,” the United States will be better positioned to direct events on the ground, determine the destination of military equipment, and support the rise of moderate voices in Syria.

Hanin Ghaddar is a Nonresident Fellow at the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East and the Managing Editor of NOW (mmedia.me). Follow her on Twitter @haningdr.

Image: French President Francois Hollande, left, is greeted by Saudi Arabia's King Salman upon his arrival at Riyadh airport, Saudi Arabia, Monday, May 4, 2015. (Reuters)