Estimates of 10,000 Yemenis protesting in the streets of Sana’a against lifting fuel subsidies have prompted international concern—mostly regarding the Houthi movement’s ability to mobilize such masses in their aggressive game of Russian roulette with the Yemeni government. The Houthi movement has threatened further action unless a new government is put in place and fuel subsidies are reinstated, placing Yemeni President Abdrabbo Mansour Hadi in an impossible situation. The recent demonstrations illustrate two deeper and more serious trends that warrant attention.

Estimates of 10,000 Yemenis protesting in the streets of Sana’a against lifting fuel subsidies have prompted international concern—mostly regarding the Houthi movement’s ability to mobilize such masses in their aggressive game of Russian roulette with the Yemeni government. The Houthi movement has threatened further action unless a new government is put in place and fuel subsidies are reinstated, placing Yemeni President Abdrabbo Mansour Hadi in an impossible situation. The recent demonstrations illustrate two deeper and more serious trends that warrant attention.

First, the Houthi movement has tapped into a reservoir of frustration and resentment among the Yemeni public that reaches far beyond its traditional support base among the Zaydi Shia population centered in the northern Sa’ada province. Second, the complete lack of attention and lack of political will to address urgent economic and fiscal crises has now brought Yemen to a near standstill. In a country where more than 50 percent of the population lives below the poverty line and 30 percent suffer from food insecurity, the overnight removal of one of the few tangible social benefits is reason enough to take to the streets. Both points glaringly illustrate the failure of the transitional government to provide economic opportunities to improve the day-to-day life of millions of Yemenis.

Instead of reshaping the political order to bring in new political voices, address corruption, and introduce responsive and accountable governance, partisan interests have largely paralyzed the transitional government, perpetuating the elite-dominated politics of old Sana’a and its tribal allies. Economic issues have repeatedly fallen off the agenda, as the president and his inner circle constantly prioritize security crises and the fight against al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) over much needed economic reforms. The international community helped Yemen form a stabilization plan, but implementation has been spotty at best. The government lacks any coordinated economic planning, with key ministers hailing from competing political parties lack any incentive to work toward a unifying vision for the country.

The Houthi movement, with its own axe to grind, managed to capitalize on palpable frustration among diverse segments of the population and fears of an Islah-dominated government (the Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated political party). Although the Houthi movement emerged as one of the big winners from the multi-stakeholder National Dialogue process that concluded in January 2014 (effectively transitioning from a rebel opposition movement to legitimate political player), they were unhappy with the final outcome and the delineation of borders for a new six-state federal system. They expected their Dialogue participation would translate into a share of political power in the cabinet and government, reflecting the new political order in the post-Saleh era, which did not happen. As a result, since April 2014, the Houthis have been resorting to arms to expand their sphere of influence, capturing the city of Amran, and even approaching the city limits of Sana’a.

The Houthi movement has been remarkably savvy and opportunistic in leveraging the pervasive sense of frustration among the broader population, calling for the formation of a new government and rallying against poor governance, lack of services, and corruption—many of the same cries heard in 2011. The recent demonstrations clearly challenge President Hadi and his internationally backed government, signaling the woefully ineffective nature of the existing political arrangement, seen as illegitimate by a growing segment of the population and potentially unsustainable.

President Hadi enjoys a relatively high degree of legitimacy, but this sentiment has never extended to the prime minister and cabinet. The current government falls short in countless arenas, particularly in addressing deteriorating socioeconomic issues, and has yet to articulate economic policies beyond how to use donor dollars allocated by the Friends of Yemen donations. The Yemeni government, in partnership with the international community, outlined and agreed to an economic plan, including structural reforms, outlined in the Mutual Accountability Plan, but never implemented it.

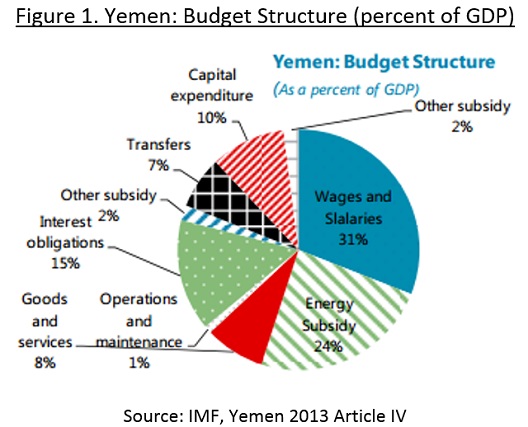

The specific case of removing subsidies is an illustration in the extreme. For years, economists and experts have highlighted the urgent need to initiate subsidy reforms in Yemen, which simply cannot sustain the massive subsidy expenditures. Yemen has among the highest level of energy subsidies in the region. Given its low per capita income and staggering fiscal deficit, the country cannot afford to subsidize energy—especially since the elite and big businesses benefit the most from subsidized prices, not the poor. In the last ten years, energy subsidies have cost a staggering $22 billion. In the first half of 2014 alone, expenditures on energy subsidies amounted to $3 billion—more than 20 percent of total public expenditures, an increase of more than 11 percent from the previous year (Figure 1).

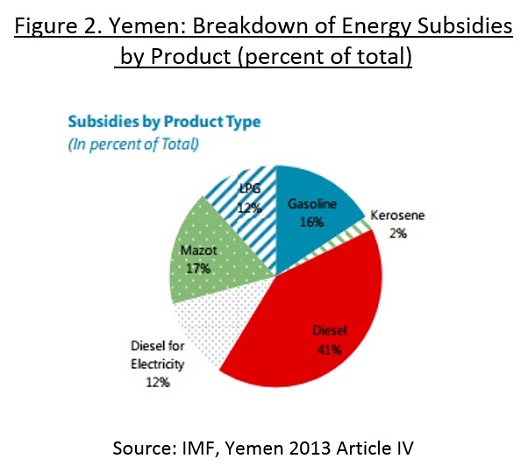

More importantly, as continued oil pipeline bombings and acts of sabotage undermine economic development, the government no longer has the fiscal space required to continue spending two-thirds of hydrocarbon revenue on subsidies. Between March 2011 and March 2013, the country lost nearly $5 billion in oil revenue, adding to the fiscal deficit expected to reach 13 percent of GDP. The recent price adjustment has brought the cost of gasoline and diesel on par with global market prices; gasoline increased by 60 percent (from YER 125 per liter to YER 200) and diesel by nearly 100 percent (from YER 100 to YER 195).

Despite the clear recognition among Yemeni experts and ministry officials that subsidies were unsustainable, the government could neither develop political consensus around this reality nor sufficiently prepare the public for the inevitable. Instead, it waited until a fuel crisis meltdown forced its hand, pushing the measure through in one fell-swoop. While necessary to salvage public finances, the rollout was an unmitigated disaster—a perfect case study of how not to introduce subsidy reform.

The cash-strapped Yemeni government had been negotiating with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for more than a year to secure a loan as a way to access much-needed financing and draw other financial commitments from donors and investors. The loan program would require the removal of subsidies, but the IMF recommends gradual price adjustments and an information and communication campaign to prepare the public. Neither of these were done. The IMF and other international donors also emphasize the need to expand the social safety net and cash transfer payments to those who would be most affected by the price increases. The United States and other donors had even increased their contributions to the Social Welfare Fund (the body tasked with distributing cash support to the poor) in the summer of 2014 in anticipation of subsidy removal. Sadly, Yemen ignored the advice.

Most importantly, the government failed to launch a comprehensive education campaign to communicate exactly what would be done and when, why energy reforms were necessary, how the most vulnerable population would be protected, and how funds would be reallocated toward other social benefits. Many Yemenis resisted the idea of subsidy removal because they lacked confidence that the money saved would be used in any way to benefit average Yemenis rather than just lining the pockets of a different group of corrupt officials. Clearly, budget transparency and buy-in from key political leaders and opinion-shapers could have mitigated some of the public outcry.

Of course, even if the Hadi government had communicated and undertaken a measured reform strategy, it is possible—perhaps even likely—that popular protesters would have taken place. The government may have intentionally avoided an official announcement to catch Yemenis off-guard, as witnessed in Egypt with the recent removal of its energy subsidies. But what Yemen’s subsidy reform exposes, beyond simple incompetence, is the unraveling of the social contract between the state and its people.

President Hadi and his government missed a valuable opportunity by not implementing a broad-based education campaign, connecting this reform to combating corruption, and engaging the Yemeni public in a discussion about what redefining the social contract will mean for them. President Hadi may have his hands full addressing the Houthi challenge to his authority, but he must now rebuild his credibility by prioritizing accountable, effective governance that can implement an economic plan oriented toward delivering concrete improvements in the daily living conditions of millions of Yemenis. Without it, the Houthis may not be the only group to challenge his authority.

Danya Greenfield is the acting director of the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

Svetlana Milbert is the assistant director for economics at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

Image: Army and police officers loyal to the Houthi Shi'ite group demonstrate near the Cabinet's headquarters to demand for the resignation of the government, in Sanaa September 1, 2014. Defying calls by the U.N. Security Council to end hostilities against the Yemeni government, Shi'ite Houthi leader Abdul Malek al-Houthi on Sunday urged supporters to wage a campaign of civil disobedience until their demands are met. (REUTERS/Khaled Abdullah)