Responding to Iranian proxies in Iraq: Lowering the cost of accountability

The February 16 attack on US forces in Erbil that killed one US contractor and injured nine others, including one US service member, represents yet another escalation in the ongoing conflict between Iran and the United States. Especially concerning is that it spreads Iraq’s sectarian violence into the Kurdish region, which has been largely free of such attacks until now. But perhaps the more immediate concern is that the attack does place the Joe Biden administration in a bind. When a similar attack happened in December 2019, the Donald Trump administration launched a series of swift and effective air strikes that killed Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) Quds Force commander Qasem Soleimani, Kataib Hezbollah leader Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, as well as a number of its fighters. However, in the aftermath of those strikes, Iran-backed militias attacked the US Embassy and the popular protests that were ongoing at the time turned against the US, leading to calls for a full American military withdrawal.

It seems the US has no good military options in Iraq: do nothing, withdraw, or get kicked out. Obviously, none of these are acceptable.

Clearly, as Secretary of State Anthony Blinken has already stated, perpetrators of the attack should be held responsible. No administration should allow attacks on Americans without making every effort to hold perpetrators accountable. However, it is not clear how to do so without making matters worse. The December 2019 fatal attack generated similar calls for accountability that the Iraqi government could not deliver. Moreover, that failure is not simply a matter of will. Iran’s proxies in Iraq are well resourced and connected throughout Iraq’s government. As a result, confronting them invites significant risks and even personal costs. Even when the government does make a good-faith effort to rein them in, as Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi did when he ordered Iraqi Security Forces to round up fourteen members of Kataib Hizballah suspected in the attack, things do not always go well. In that case, their comrades were able to get them released within hours. What followed was a very public denouncement of Kadhimi that highlighted weakness rather than the hoped-for resolve.

Further confounding a US response is the uncertainty associated with fighting proxies. Awliyaa al Dam, the group that claimed responsibility for the attack, is very likely a re-branded Kataib Hezbollah, which is essentially an arm of the IRGC. Yet, whatever the US government actually knows about the perpetrators, the fact that the attack is attributed to a little-known militia limits the options the US can take. Awliyaa al Dam would likely be difficult to target unilaterally. However, striking at Kataib Hezbollah or even Iran will allow both to seize the narrative and portray the US as the destabilizing actor, repeating late 2019 and early 2020, when Iraq’s parliament voted to recommend the expulsion of US forces.

However, the fact that these attacks happened in Kurdistan represent an opportunity to model an effective bilateral response. Most Kurds continue to welcome a US security presence and are likely willing to support action taken against Awliyaa al Dam, regardless of whom it actually turns out they work for. Moreover, the Kurdish Regional Government is more resistant to Iranian influence and its security forces are more likely able and willing to find, detain, and, if necessary, kill these proxies who conducted the attack. It would be in the US’s interest to work closely with these local forces and provide what support they require to effectively respond to the attack rather than doing so on its own. In the end, it is in US, Iraqi, and Kurdish interests that the process of holding the attackers responsible resembles a law enforcement operation more than a military one, regardless of the forces used.

In doing so, however, the US also needs to coordinate closely with Baghdad, who will see any use of force they do not sanction, even in Kurdistan, as a violation of Iraqi sovereignty. The perception of such a violation will bolster Iran’s narrative of the US as the destabilizing influence in Iraq, which will lead to additional calls not just to withdraw US military forces from Iraq, but to limit other forms of cooperation.

Even without Iranian influence, the Baghdad-Erbil relationship is subject to domestic opinion that exacerbates the tension between them. Thus, any joint US-Kurdish response that does not involve Baghdad will likely be met with the same kind of protest that a unilateral response would have garnered. The point here is that whatever approach the US adopts to defend itself against attack, it makes little sense to do so in a way that increases tensions between Baghdad and Erbil.

The US can avoid this outcome—but only by ensuring that any response corresponds to the interests of Baghdad and Erbil and makes them more, not less, resilient against Iranian and domestic pressure for a US withdrawal. Of course, the US may need to apply some pressure to get the cooperation it requires. Nevertheless, while perhaps a slower response, doing so can improve on the current “no-win” alternatives that unilateral options would entail. Rather than being faced with doing nothing, leaving, or being kicked out, such a joint approach can make the US the more attractive partner, undermine Iran’s ability to control the narrative, and improve prospects for future security cooperation.

Dr. C. Anthony Pfaff is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Iraq Initiative and research professor for Strategy, the Military Profession, and Ethic at the US Army War College’s Strategic Studies Institute. The views expressed here are those of the author and not necessarily the US Government.

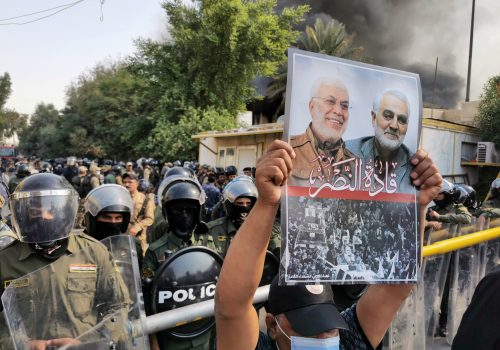

Image: People stand next to a roof damaged after a rocket attack on U.S.-led forces in and near Erbil International Airport last night, in Erbil, Iraq February 16, 2021. REUTERS/Azad Lashkari