As US officials have repeatedly acknowledged, Bashar al-Assad’s military “calculation” ultimately must change to enable a negotiated political transition. One option under consideration is a no-fly zone over parts of Syria. As with any exercise weighing the costs and benefit of a specific course of action in Syria, the discussion of a no-fly zone starts with objectives: what would the United States wish to accomplish?

In August 2011 President Barack Obama declared that Assad should step aside. Since then the president and other senior officials have defined the US objective in Syria in terms of a political transition from authoritarian family rule to a pluralistic system reflecting rule of law and civil society. "Democratic, plural system" is also the phrase used in UN Security Council Resolutions 2042 and 2043.

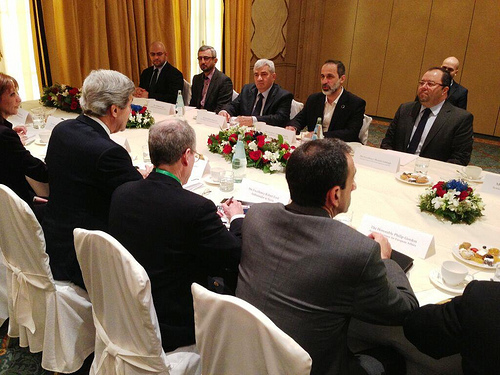

The president and others have also specified that this transition should be the result of Syrian negotiations reflecting the process and prospective results outlined by the June 2012 Final Communiqué of the Action Group for Syria. A follow-up international conference, this one including Syrian parties, is expected to take place in about two weeks.

The administration prefers that Syria’s political transition come about through negotiations between the Syrian government and the Syrian opposition, because it believes a negotiated settlement would avoid one of the harsh lessons learned in Iraq: that the complete collapse of the state and dissolution of governmental institutions can engender deep resentments and help spark an insurgency.

The administration’s preference for a negotiated compromise that would remove the family regime while preserving key institutions of government helps to explain why it has invested so little in a rebel military victory. This was true even a year ago, when arming vetted units of the Free Syrian Army would have been much less complicated than it would be now. Some senior US officials have even gone so far as to say that a quick rebel victory would be dangerously destabilizing.

However, the administration’s challenge is that the struggle for Syria has become totally militarized and that its preferred way forward seems to enjoy scant support among those Syrians who have irrevocably chosen sides in this conflict, including those doing the shooting. It is possible that that a majority of Syrians would actually favor the administration’s approach: out with the Assad family and in with a national unity government dedicated to stability and reform while preserving, to the maximum extent possible, the institutions of national government. But even if this is the majority view it does not, regrettably, seem to be terribly relevant at the moment.

The salient fact is that the Assad regime, basking in the glow of complete Iranian and Hezbollah commitment to its survival, seems to believe it can prevail militarily. It will send a delegation to Geneva mainly in the hope that the opposition will not. A key element of the regime’s military strategy is to terrorize presumed hostile civilian populations. In those areas it can reach by ground it does so by commissioning shabiha auxiliaries to commit massacres. In those areas it cannot reach by ground it does so through indiscriminate shelling and bombing. The effects of these terror operations are to send waves of refugees across international borders, create an internally displaced population in the millions, and kill, wound, and maim noncombatants by the tens of thousands.

The administration has concluded that Assad’s "calculation" must change for the regime to be at all disposed toward a negotiated compromise that would include the end of family rule. Some hope Russia will change that calculation. It appears, however, that Assad’s calculates mostly (if not exclusively) on his assessment of the military situation on the ground.

Protecting civilians, shielding US allies and friends from the effects of the regime’s war of terror, and changing Assad’s calculation all come together in the minds of many commentators under the broad rubric of the no-fly zone. Again, it is useful in this context to know the desired effects. The United States’ objective in this scenario could, for example, be to eliminate or seriously degrade the ability of the Assad regime to conduct missile, aerial, and artillery attacks against populated areas. The manner by which this objective would be achieved, if adopted by the president, would be determined by military professionals. Much might be achieved, for example, through the employment of stand-off weaponry to destroy regime weapons systems and support facilities on the ground rather than imposing a no-fly zone as was done in Iraq and the Balkans.

Regardless of the methodology, however, what would be required is a decision by the president, in consultation with Congress, to go to war. The regime will not, after all, consent to our use of military force on Syrian territory. There is no point in sugarcoating this reality.

If the United States decides to go to war it will almost certainly not have the benefit of a Chapter VII UN Security Council resolution, which would be the clearest international legal basis for either employing a no-fly zone or destroying regime assets on the ground. Nor would it be able to make a clear case under the self-defense provision of Article 51 of the UN Charter, although some would argue that a grave threat to regional peace and stability could amount to sanctioned self-defense so long as there is no attempt to seize the offending country’s territory or challenge its independence. Although a relatively new doctrine of humanitarian intervention has its strong adherents, nothing close to a consensus has emerged around the "responsibility to protect" thesis. In sum, a US decision to go to war in Syria under current circumstances would have to be taken in a context where international authorization would be somewhere between nonexistent and extremely contentious.

These circumstances could change dramatically were there an alternate Syrian government established on Syrian territory, one which the United States and many others would recognize as the legitimate, legal government of Syria. Such a government would be entitled to request assistance in its defense from those who recognize it. The United States and others would be entitled to offer defensive assistance to counter the Assad insurgency and its foreign fighters. This scenario would not preclude national unity negotiations between the new Syrian government and an entity in Damascus still recognized by Russia, Iran, and others.

Regardless of the circumstances prevailing, if the United States elects to eliminate or seriously degrade the ability of the Assad regime to conduct terror operations, two other key ingredients must be part of the policy mix. Consultations – with Congress and with those international actors whose support and assistance we will want – are absolutely essential. And to prevent unconscious mission creep the United States will need to define mission accomplishment in specific operational terms.

Finally, unless the administration changes its strategic objective and acts accordingly, it is at least hypothetically possible that the United States could accomplish the mission of eliminating or seriously degrading regime mass terror capabilities and still witness the regime (with Iran and Hezbollah "all in") either win an outright military victory or retake populated areas, where it can kill, stampede, and terrorize face-to-face instead of using artillery, aircraft, and missiles. A regime whose aerial and artillery assets are largely destroyed or essentially neutralized surely would be less capable militarily than it is now. But this is a war Iran and Hezbollah, and arguably Russia, have decided not to lose; they are committed to a regime victory, while the administration has shown no such resolve or commitment to a rebel military victory. The administration must ask itself whether a victory in Syria by those three is acceptable, or whether it could have destabilizing consequences that far transcend Syria.

*This article is based on the author’s remarks at the U.S. Institute of Peace on May 29.

Frederic C. Hof is a senior fellow of the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East at the Atlantic Council and the former special advisor for transition in Syria at the US Department of State. Photo Credit.

Image: Syria_0.jpg